When Erica Barnell was an MD/PhD student at Washington University in St. Louis, she met a woman who had stage four colorectal cancer (CRC). The woman was only 52 years old—more than a decade younger than the median age of a person who receives a CRC diagnosis, which is 68 years old.1 She had not been screened for colon cancer because she couldn’t take time off work and was busy with her kids.

Colon cancer screenings can help detect cancer early, which leads to better treatment outcomes than late detection. “There’s an ample window of opportunity to intervene,” said Paul Limburg, the chief medical officer for screening at Exact Sciences. “Anywhere from 10 to 15 years is the estimated timeframe for a normal colonocyte, a cell lining the colon or rectum, to progress through various stages of abnormality to become an invasive cancer.”

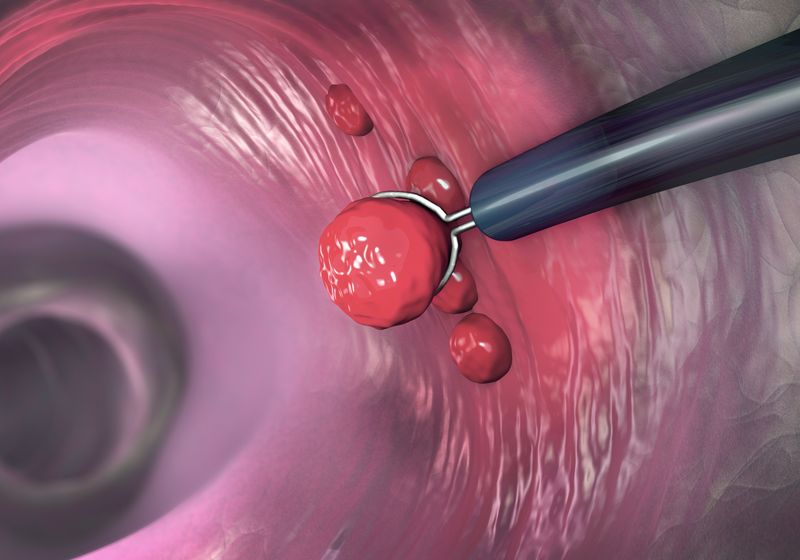

Colonoscopies, a time-intensive procedure that typically requires a day of prep and anesthesia, is considered the gold-standard for colon cancer screening. “It’s the most sensitive and the most specific from a technical standpoint for detecting the premalignant lesions…as well as for detecting colorectal cancer at any stage,” said William Grady, a gastroenterologist at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center and a scientific advisory board member of the precision medicine company Guardant Health. Doctors recommend colonoscopies every five years starting at age 45 for people with an average risk of developing colon cancer.2 “We’ve had colonoscopies since the ’70s, and only 60 percent of patients are compliant with recommended screening,” said Barnell, who added that for people between the ages of 45 and 50, the compliance rate drops to about 30 to 35 percent.

Barnell’s encounter with the young CRC patient spurred her to co-found the company Geneoscopy in 2015, which offers a CRC screening test based on RNA found in the stool. The test, ColoSense, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last year and is one of the several non-invasive colon cancer screening tests approved in the last couple of years.

While non-invasive tests can make screening easier for people and encourage uptake in those who might not otherwise get a colonoscopy, they have historically been less accurate than colonoscopies. Newer tests are changing that, improving sensitivity and specificity of detection. The question is, can these tests, and should they, replace colonoscopies?

From Blood to Molecular Biomarkers: The Progression of Non-Invasive CRC Screening

Erica Barnell, co-founder of Geneoscopy, thinks that non-invasive options are becoming first-line tests for colorectal cancer, particularly for people who otherwise wouldn’t get a colonoscopy.

Geneoscopy

The first non-invasive CRC screening tests aimed to identify blood in the stool. As CRC tumors grow, they can cause bleeding in the colon. While the blood can sometimes be visible to the naked eye, this isn’t often the case. Scientists designed tests called fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) to detect blood in stool samples. One version of FOBT, called fecal immunochemical test (FIT), uses antibodies that bind either to hemoglobin alone or to the hemoglobin/haptoglobin complex.3 While the FIT test is commercially available, researchers have now incorporated the detection of occult blood into more comprehensive screening tests.

Many of the recently approved colon cancer screening tests target multiple signatures of the disease, including DNA mutations and abnormal DNA methylation patterns in addition to the presence of blood in the stool. An early version of such a test came from Exact Sciences which developed the Cologuard screening test that was approved in 2014. This test uses collected stool samples to look at three elements: hemoglobin in the stool using an ELISA-based assay; seven point mutations in KRAS, a gene mutated in about 40 percent of CRC cases; and abnormal methylation in the promoter regions of BMP3 and NDRG4, which are genes associated with colon cancer.4,5

To evaluate a screening test, researchers assess two main metrics: sensitivity, the proportion of true positives correctly identified, and specificity, the proportion of true negatives correctly identified. The Cologuard test had a sensitivity for detecting CRC of 92 percent and a sensitivity of 42 percent for detecting advanced precancerous lesions.4 This compares to a sensitivity of 95 percent of colonoscopies for detecting CRC.6 Cologuard correctly identifies nine out of 10 people who had a negative colonoscopy result, but one in 10 people from this group received a false positive result.4

Paul Limburg, chief medical officer at Exact Sciences, thinks blood-based options could help identify CRC in people unwilling to use another screening method.

Exact Sciences

In an effort to reduce the number of false positives in the Cologuard test, Exact Sciences came out with another test called Cologuard Plus about a decade later. This new test, which the FDA approved in 2024, identifies four methylation markers and hemoglobin. “It’s a simplified assay,” said Limburg, who mentioned that adding in additional mutation markers did not seem to change the performance of the test. Sensitivity was 95 percent for CRC and 43 percent for advanced precancerous lesions.7 Because the screening interval is three years for Cologuard Plus versus five years for colonoscopies, Limburg said that there are “more chances to pick up those advanced pre-cancers” with the more frequent screening interval used for Cologuard Plus. Compared to Cologuard, Cologuard Plus increased specificity to 94 percent, which Limburg anticipates will translate to 40 percent reduction in unnecessary follow-up colonoscopies after a false positive result.

At Geneoscopy, Barnell turned to RNA as biomarkers for her team’s ColoSense test. This test quantifies eight RNA transcripts using digital PCR and the presence of hemoglobin in the stool.8 Biomarkers included in ColoSense include common genetic contributors to CRC: KRAS, TP53, Wnt pathway, and MAP4 pathway components. “We definitely didn’t reinvent the wheel in terms of biomarker discovery,” Barnell said. She added that her team was more interested in improving the detectability of these signals in samples that patients could collect in the comfort of their own homes and send into the company. When Barnell and her team validated the test as part of the Colorectal Cancer and Pre-Cancerous Adenoma Non-Invasive Detection Test clinical trial, it had a 94 percent sensitivity for CRC and 46 percent sensitivity for advanced adenomas, which are larger adenomas with higher risk of developing into CRC.8

While RNA is inherently more unstable than DNA, using RNA biomarkers has an advantage over DNA. “They’re not subjected to the age-related processes that are attributable to other biomarkers such as methylation,” Barnell said. For tests that analyze methylation, she mentioned that “sensitivity in the younger patient population is significantly reduced…By using RNA biomarkers, we have consistent accuracy across all age ranges.” When her team assessed the ColoSense test in younger populations, between 45 and 49 years old, ColoSense had a sensitivity of 100 percent for CRC and 45 percent for advanced adenomas.8

Blood-based Liquid Biopsies Offer Another Option

While stool-based tests have been more established, newer tests are turning to blood. Blood tests are simpler and routine for people, and they don’t have the “ick” factor associated with collecting stool. But for now, these tests are generally less accurate. “The way we are thinking of blood-based tests is that they are for patients who are unwilling to pursue screening with any of the other recommended options,” said Limburg.

A recently approved blood-based test is Shield from Guardant Health. This test looks for abnormal methylation patterns in cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which are DNA fragments released by tumors that can make their way into blood. Shield looks for somatic mutations, fragmentation patterns, and abnormal methylation in cfDNA representing more than 2,000 genomic regions. The FDA approved this test in 2024, and in average-risk populations it has a sensitivity of 83 percent for CRC and 13 percent for advanced precancerous lesions.9

Chuan He, a chemist at the University of Chicago, applies chemistry to develop genomic methods, including one that could be used for colon cancer screening.

Jason Smith

While Shield, the Cologuard tests, and ColoSense all examine cancer signatures from human cells, Chuan He, a chemist at the University of Chicago, is turning towards microbial RNA signatures to screen for CRC. Like cfDNA, cell-free RNA (cfRNA) can make its way into the blood. However, detecting cell-free RNA derived from cancer cells has been challenging because of the low levels of cfRNA released into the blood from these cells. When mapping cfRNA to the genome, He noticed that between 20 to 40 percent of the cfRNA mapped to microbial genomes.10 Because microbes have a short lifespan compared to human cells, they also quickly release a “good portion of material in the blood,” He said. This can be an advantage, He explained, because “the microbiome is constantly responding to host conditions. That gives you a more up-to-date view of what’s happening.”

Using blood samples from 27 people with CRC and 36 age-matched healthy controls, He and his team investigated the methylation of microbiome-derived cfRNA using a technique called low-input multiple methylation sequencing (LIME-seq), which detects and quantifies multiple types of RNA modifications in low concentrations of cfRNAs. He and his team found that the method was 95 percent accurate in making CRC predictions.10 “When we use these modifications as a biomarker, we get unprecedented detection, sensitivity, and specificity when we look at colorectal cancer, particularly at the early stage,” said He. His team is repeating these analyses in a larger cohort size to validate these findings, and they hope to develop the test into a panel for early diagnosis.

A Replacement for Colonoscopies?

The non-invasive tests on the market are screening tests meant to find signs of disease in asymptomatic individuals and not to diagnose disease. “The only way we feel confident that somebody has a diagnosis of colorectal cancer is to have tissue,” said Grady. “Colonoscopies can do that.”

William Grady, a gastroenterologist at Fred Huch Cancer Center, identifies biomarkers from blood, stool, and urine that could help screen for colon cancer.

Robert Hood/Fred Hutch Cancer Center

However, with low compliance rates of colonoscopies, non-invasive diagnostics could improve the chances of detecting cancer early at a population level. But not all screening tests are equivalent. Colonoscopies and stool-based tests are, for now, more accurate. If too many people who would have been willing to get one of these options switch to a blood test, rates of CRC deaths will increase.11 “If you can get a blood test over 95 percent sensitivity and specific, and it’s non-invasive from blood, then that could be really widely used,” said He. Even then, a positive result from a blood-based or stool-based test would still require a follow-up colonoscopy to make a diagnosis. However, only about half of individuals with a positive result end up getting a follow-up colonoscopy.12,13

“Over time, if they were to get to be 100 percent specific, then we would feel confident doing that, but I don’t think that’s in the near future on our horizon,” said Grady, who noted that since treatments for CRC are so severe and toxic, any new diagnostic test would need to meet a very high standard to be accepted.

Concurring with Grady, He added, “I think that we’ll have to wait and see.”

- Ilyas MIM. Epidemiology of stage IV colorectal cancer: Trends in the incidence, prevalence, age distribution, and impact on life span. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2024;37(2):57-61.

- Wolf AMD, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250-281.

- Méndez G, et al. Faecal occult blood testing: A review of its use and common misutilisation. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2025;12(1):e001876.

- Imperiale TF, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297.

- Zhu G, et al. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the prognosis, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):143.

- Jacobsson M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2024;104(3):595-607.

- Imperiale TF, et al. Next-generation multitarget stool DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(11):984-993.

- Barnell EK, et al. Analytical validation of the multitarget stool RNA test for colorectal cancer screening. J Mol Diagn. 2024;26(8):700-707.

- Chung DC, et al. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(11):973-983.

- Ju CW, et al. Modifications of microbiome-derived cell-free RNA in plasma discriminates colorectal cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2025.

- Ladabaum U, et al. Projected impact and cost-effectiveness of novel molecular blood-based or stool-based screening tests for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(12):1610-1620.

- Zaki TA, et al. Colonoscopic follow-up after abnormal blood-based colorectal cancer screening results. Gastroenterology. 2025.

- Ciemins EL, et al. Development of a follow-up measure to ensure complete screening for colorectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242693.