The last several years have marked a time of breakthroughs on the long and rocky road to effective Alzheimer’s disease treatments. After decades of failure, two antibodies designed to target forms of amyloid-β (Aβ) were shown to halt cognitive decline, results warranting FDA approval. However, these new treatments have drawbacks—they are expensive, have complicated infusion schedules, and come with a risk of adverse reactions like brain swelling and bleeding (ARIA), especially prevalent in people with the APOE4 gene variant associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

Earlier this week, a small biotech company called Alzheon, situated in Framingham, Massachusetts, demonstrated data that has the potential to change the way Alzheimer’s is treated, especially for APOE4/4 homozygotes. In a peer-reviewed research article, Alzheon reported results from its Phase III APOLLOE4 trial evaluating the oral drug ALZ-801 (valiltramiprosate) in individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease who are APOE4 homozygotes. The drug slowed cognitive decline, nearly doubled the brain’s functional preservation, and reduced brain shrinkage without causing the blood vessel problems often associated with antibody treatments.

“This is the population at the highest genetic risk but also the one most at risk from the safety issues we see with antibody drugs,” Susan Abushakra, MD, Alzheon’s chief medical officer and lead author of the study, told Inside Precision Medicine. “Our results show that you can achieve meaningful slowing of disease progression without the brain swelling or bleeding that makes physicians cautious about treating APOE4 carriers.”

Beyond antibodies

Neurologist Abushakra has spent over 20 years developing Alzheimer’s disease drugs, seeing the field move from blind experimentation to biological precision. “In the last five to ten years, the biggest change has been our recognition that Alzheimer’s disease has a biological definition,” Abushakra said. “You have to have amyloid pathology to start calling it Alzheimer’s disease. Once people develop both amyloid and tau pathology, that’s when it becomes the symptomatic state—Alzheimer’s dementia.”

This clearer biological framework has transformed how companies design and test drugs. With blood-based biomarkers and PET scans for amyloid and tau, Alzheimer’s can be detected earlier and more accurately. “These advances have made clinical trials more intelligent and rational,” said Abushakra. “We can now enroll patients based on biology, not just symptoms.”

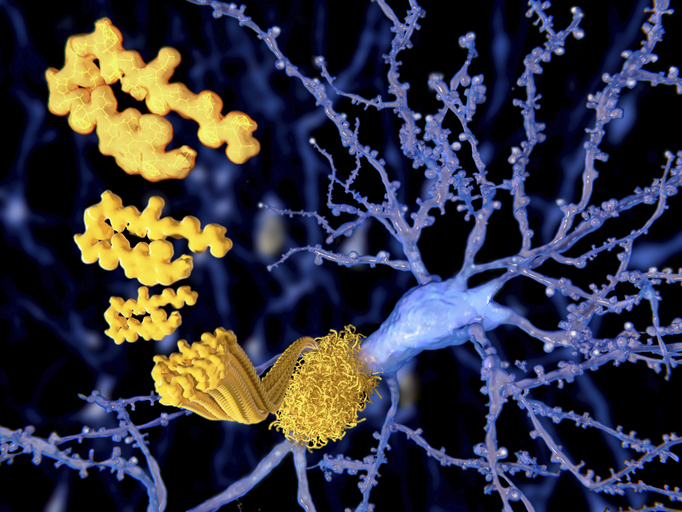

This new scientific understanding led to Eli Lilly’s donanemab and Eisai and Biogen’s lecanemab (Leqembi), the first Alzheimer’s treatments to change progression rather than just alleviate symptoms. Donanemab and lecanemab are monoclonal antibodies designed to clear toxic forms of Aβ, but they act at different stages of amyloid buildup. Donanemab targets a modified, plaque-bound form of Aβ (Aβp3–42), rapidly clearing established deposits from the brain. Lecanemab binds to soluble amyloid-beta protofibrils, precursors to plaques, to prevent neurotoxicity.

Both antibodies reduced brain amyloid plaques as well as cognitive and functional decline in early-symptomatic Alzheimer’s patients in large Phase III trials. “It’s a huge advance,” Abushakra said. “For a long time, Alzheimer’s trials weren’t successful. Now we have treatments that slow the disease. But the benefit, while meaningful, is modest—and the safety concerns are real.”

However, safety concerns that disproportionately affect APOE4 carriers have dampened enthusiasm for these antibody therapies. When antibodies attack amyloid deposits in blood vessel walls, they leak or rupture, causing ARIAs like brain edema (ARIA-E) and microhemorrhages (ARIA-H). “Most ARIA events are small and asymptomatic,” Abushakra explained. “But some can be large bleeds or significant swelling. They can cause serious neurological events or even be fatal.”

Due to these risks, the FDA requires APOE genotyping before antibody therapy and includes warnings in drug labels. “If people have one or two APOE4 alleles, they’re at much higher risk of ARIA—especially the homozygotes,” said Abushakra. “This has created a real dilemma: the very patients who are most at risk for the disease are the ones least safely treated by the approved drugs.”

That problem defines Alzheon’s mission. The company’s founders—veterans of the amyloid field—set out to develop a drug that could reach the same biological target without triggering vascular damage. ALZ-801, a small-molecule oral drug, prevents soluble Aβ monomers from misfolding and forming toxic oligomers and protofibrils. “Amyloid monomers may have normal physiological functions in the brain,” Abushakra explained. “The problem starts when they misfold and clump together into oligomers. These small aggregates can move around, injure neurons, and disrupt synaptic activity—marking the beginning of cognitive symptoms.”

Individuals with the APOE4 genotype tend to have higher oligomer levels because their brains clear amyloid less efficiently, making them a logical target for ALZ-801. “APOE4 is the single most important genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease after age,” said Abushakra. “If you have one copy of APOE4, your lifetime risk increases about fourfold. If you have two copies, it’s about 14 times higher—roughly a 60% chance of developing the disease.”

ALZ-801 (valiltramiprosate) is a prodrug of tramiprosate, an earlier molecule that showed promise in post-hoc analyses of prior studies but suffered from poor bioavailability and variable absorption. The new formulation provides more consistent plasma levels and better brain penetration. “We reformulated it for better absorption and tolerability,” Abushakra said. “In earlier studies, we saw that APOE4 homozygotes had the most convincing benefits, so we focused our pivotal program on that population.”

Inside the APOLLOE4 trial

The Phase III APOLLOE4 trial enrolled individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease—covering both the MCI and mild dementia stages—who were homozygous for APOE4. At 78 weeks, ALZ-801 slowed hippocampal atrophy (18%) but did not improve cognition or daily function in all early Alzheimer’s disease patients compared to controls. In MCI patients, the drug showed greater prevention of hippocampal atrophy (26%) and slowed cognitive decline by 52% on the ADAS-Cog13 (Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Cognitive subscale, 13-item version), a widely used clinical assessment tool that tests memory, language, and attention to assess severe cognitive impairment. “In the MCI subgroup, we saw clinically meaningful and statistically significant benefits in cognition and function,” said Abushakra. “We slowed cognitive decline by about 52% compared to placebo, and we reduced the progression of disability.”

ALZ-801 reduced disability progression by 96% according to the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD), which measures cognitive impairments like dementia patients’ daily living skills. Nausea, vomiting, and appetite loss were the most common side effects, but brain swelling and microbleeds were not. Crucially, the trial reported no increase in ARIA-E or ARIA-H compared to placebo. “We had the same rate as placebo,” said Abushakra. “Basically, none of the patients had symptomatic ARIA. It’s a very strong safety profile, especially in this high-risk population.”

Many APOE4 homozygotes, who constitute about 15% of the Alzheimer’s population in the U.S., have been excluded or discouraged from antibody treatment because of safety concerns. “This is a group with accelerated disease progression and limited therapeutic options,” said Abushakra.

Accessibility is a key part of the ALZ-801’s promise. While lecanemab and donanemab require intravenous infusions every two to four weeks at specialized centers and routine MRIs to monitor for ARIA, ALZ-801 could be prescribed broadly across healthcare settings and taken at home. “Having a simple oral tablet they can take twice a day at home—with meals, without infusion centers or MRI monitoring—would be a major advantage,” said Abushakra. “You could take this kind of drug whether you live in a major city with academic medical centers or in a small rural community. That’s essential when you’re talking about millions of people with early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Toward precision medicine in Alzheimer’s

The APOLLOE4 study also advances a broader vision: precision medicine in neurodegeneration. Genetic and biomarker profiles could be used to prescribe ALZ-801 as genetic testing becomes more common and APOE genotyping is integrated into clinical workflows. “People are increasingly learning about their genotype, either through clinical testing or direct-to-consumer platforms,” she said. “It allows for early awareness and planning, but also for targeting treatments to those who need them most.”

That targeted approach could extend beyond APOE4 homozygotes. “We think heterozygotes will probably respond as well,” Abushakra noted. “We have data suggesting benefit there too, and future studies will likely expand into that population.”

The growing acceptance of APOE genotyping could speed up Alzheimer’s pathology prevention and treatment, which develops 15–20 years before symptoms appear. Abushakra explained, “Even at the MCI stage, the process has been ongoing for decades.”

While the APOLLOE4 trial focused on patients already showing symptoms, the Alzheon team sees prevention as the next frontier. Researchers can now identify at-risk individuals before cognitive symptoms appear using plasma biomarkers that detect early amyloid and tau changes in the blood. “That’s where the field is moving—to what we call secondary prevention,” said Abushakra. “These are people who already have amyloid pathology but haven’t lost many neurons yet. Blocking that process early could be the best time to intervene.”

Because ALZ-801 is oral and safe, it could be ideally suited for preventive use. “If you can start an oral drug before symptoms begin, in people who have biomarker evidence of pathology, that could change the trajectory of the disease entirely,” she said.

Beyond monotherapy: the next wave

Despite Alzheon’s best efforts to recruit participants from a variety of backgrounds, APOLLOE4 failed, as have most Alzheimer’s trials, to achieve broadly representative demographics. “We achieved about 12% representation of non-Caucasians,” said Abushakra. “We worked with community physicians, went into major cities like Los Angeles, and partnered with local organizations to reach underrepresented groups.”

Those efforts are particularly important because APOE4 prevalence varies by ethnicity. Though highest in Northern Europeans and slightly lower in African Americans and Asians, it affects disease risk and progression across all groups. “We’re continuing to strengthen our outreach to ensure our studies reflect the diversity of the Alzheimer’s population,” Abushakra said.

Abushakra sees combination therapy, a common oncology concept, as a solution to Alzheimer’s genetic complexity. “In the future, you might start patients on an antibody to quickly clear amyloid plaques and then maintain them on an oral agent like ALZ-801 to prevent re-aggregation,” she suggested. “That could deliver much stronger and longer-lasting clinical benefits.”

Alzheon continues to collect data from APOLLOE4 and its two-year extension study, which will follow open-label treatment participants. The company is also analyzing advanced imaging data using diffusion MRI to assess changes in brain microstructure. “These imaging modalities can tell us not just about volume loss but about the integrity of brain networks,” Abushakra said. “We expect to share more of those findings soon.”

The Alzheimer’s field has seen many promising signals fade under the scrutiny of replication. Alzheon’s Phase III results will need to be confirmed in larger, independent studies and potentially across broader genotypes. But the scientific rationale is strong, and the unmet need is undeniable.

A twice-daily pill with meaningful efficacy and no ARIA risk could transform early Alzheimer’s patients and families. “We’re optimistic,” Abushakra said. “For the first time, we can imagine a precision-medicine approach to Alzheimer’s that’s safe, accessible, and tailored to those at greatest risk.”

If the APOLLOE4 data signal anything, it’s how far Alzheimer’s research has come from its uncertain beginnings. Modifying disease biology was unthinkable when Abushakra started her career. Today, antibodies, small molecules, vaccines, and gene therapies are being developed based on a better understanding of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We’re not just chasing plaques anymore,” she said. “We’re intervening earlier, based on biology, and tailoring therapies to each patient’s genetic and molecular profile. That’s what makes this moment so exciting.”

For a disease that affects more than seven million Americans and twice that number in its prodromal stages, even incremental progress matters. But the APOLLOE4 story hints at something bigger: a future where Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment are as personalized—and as safe—as managing cholesterol or hypertension.

“We’ve reached the point where we can finally say with confidence that Alzheimer’s disease is modifiable,” Abushakra said. “Now, the challenge is to make those treatments safer, earlier, and accessible to everyone who needs them. That’s what drives our work at Alzheon.”