You will have seen the images: the maternity hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, in 2022—its exterior ripped away, wards reduced to rubble, wounded pregnant women and newborns carried from the debris. A year later, Al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza City after a major explosion—the burnt-out cars, blown windows, and bodies of blast victims laid beneath hastily constructed tents. These scenes have renewed calls to protect medical facilities in conflict zones. If such images feel almost normal now, that’s because they are.

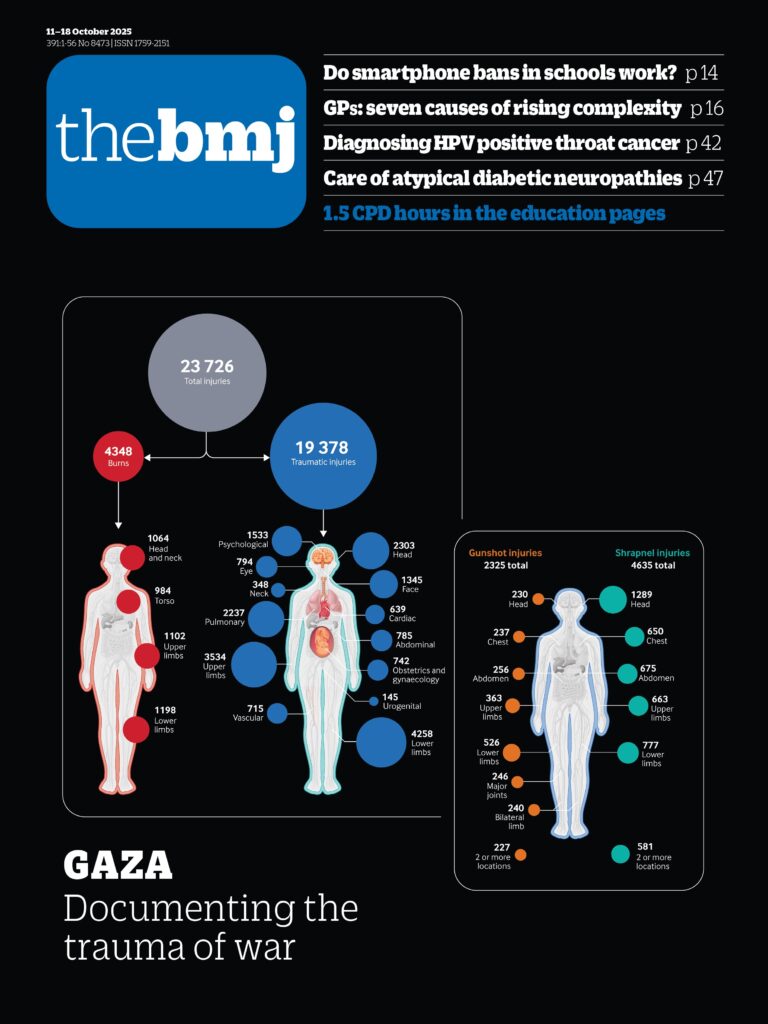

This week The BMJ uses infographics and data to show how attacks on healthcare have become a deliberate strategy of war (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2153).1 From 2020 to 2024 the number of these attacks tripled, as combatants increasingly used highly explosive weapons—missiles, rockets, bombs—without distinguishing between military and civilian targets. Conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza have driven this escalation, but it is global, with clusters in Myanmar and sub-Saharan Africa.

Even against this grim backdrop, the scale of attacks in Gaza is unprecedented. “I have never seen anything like the almost daily attacks on hospitals . . . the indifference to the consequences of the attack to patients and staff,” says Len Rubenstein, a conflict expert. Witness the cruelty of “double tap” strikes: hospitals are hit, rescuers flood in, and the bombardment resumes. And the toll isn’t only in death and injuries. Health services are left unable to function. A generational impact is already being seen in Syria, where the destruction of hospitals has altered the practice of medicine in the long term. Some facilities will never be rebuilt, patients are afraid to seek care, and medicine is seen as a high risk profession.

Most attacks over the past five years have been by state actors—but what would work as a deterrent when there’s no consequence? Criminal prosecutions are slow and rare. But governments can still act by ending the supply of weapons to perpetrators who strike healthcare, upholding the principle that it should never become a target.

Elsewhere, global communities are feeling the pinch as they are pulled into the dragnet of economic and ideological change in the US. Essential medical technologies are paying the price for opaque trade policies: for example, wheelchairs and prosthetics are among products caught in fragile global supply chains (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2086).2 Robert F Kennedy Jr’s distrust of “experts” feeds an atmosphere where healthy doubt is “deliberately weaponised” to erode trust in expertise (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2077).3 Predictably, vaccines are the most obvious casualty: the resurgence of pertussis in infants is a stark example, where maternal vaccination is effective but uptake has fallen sharply in the UK and elsewhere (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2169).4

In the NHS there are parallel fears that expertise is being reduced to a set of “tasks” (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2082),5 where complex care is broken up into measurable fragments. But as Matt Morgan warns, “Slice work into tasks and you amputate judgment.” And sometimes the most powerful expression of medical expertise is the care you decide not to give (doi:10.1136/bmj.r2178),6 such as when not to treat osteopenia (doi:10.1136/bmj-2025-085622 doi:10.1136/bmj.r2154).78

The erosion of trust—in professionals, institutions, and the values that underpin healthcare—is a common thread. Rebuilding that trust, whether in clinical judgment or in medical neutrality during conflict, is an essential task facing medicine today.