You have full access to this article via your institution.

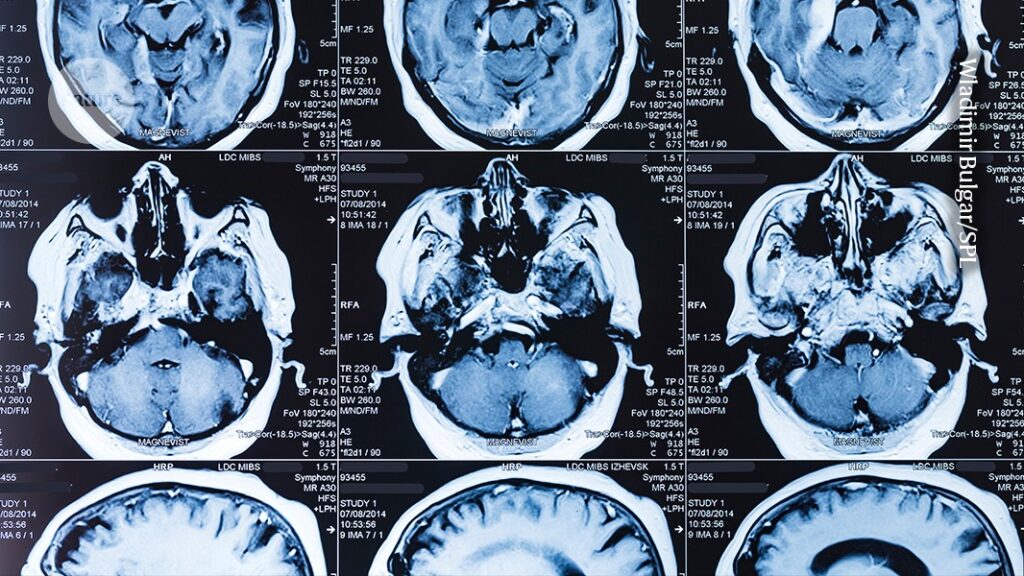

MRI is among the breakthrough technologies that emerged from fundamental, curiosity-driven science.Credit: Wladimir Bulgar/SPL

Around the world, budgets for fundamental research — studies that seek primarily to advance knowledge for its own sake, without an expectation of a return on investment — are coming under pressure to an extent not seen for at least a generation.

In the United States, the principal funder of fundamental research, the National Science Foundation, has this year terminated some 1,600 grants worth a total of US$1 billion, a huge chunk of its $10 billion budget. And US President Donald Trump has proposed slashing its budget by 55%. Meanwhile, in the European Union, competition for funding will only worsen if the bloc implements a misguided plan to include defence and security research in its Horizon Europe programme, which has previously funded only civil research projects.

7 basic science discoveries that changed the world

China has bucked the trend. Last week, the nation’s leadership announced that funding for fundamental research will increase in the country’s next five-year plan, for 2026 to 2030. But elsewhere, as global conflict and pressure on public spending grows, we are hearing funders from Australia to the United Kingdom argue that research with a direct real-world impact — ideally economic — is preferable to fundamental research. In other words, basic research is nice to have, but dispensable in straitened circumstances.

A News Feature in Nature this week offers a reminder of why this approach is wrong-headed. It describes world-changing ‘blue skies’ research that was mostly or entirely about acquiring knowledge, and only later found to have wider applications. In some cases, such discoveries have improved or saved millions of lives.

The polymerase chain reaction — the fundamental science behind the PCR tests used to identify bacteria and viruses that became a part of daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic — originated from work on bacteria found in hot springs by the microbiologists Hudson Freeze and Thomas Brock at Indiana University in Bloomington. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) emerged from the study of the fundamental physical properties of the atomic nucleus, and studies of venomous lizards played a key part in the development of drugs such as Ozempic that mimic the GLP-1 hormone. Flat-screen televisions have their roots in studies of chemicals that were isolated from carrots. The News Feature covers seven prominent examples, but there are numerous others.

Is academic research becoming too competitive?

It is true to say that, overall, today’s research-funding environment bears little resemblance to that of decades gone by. In the twentieth century, many scientists performed research work alongside their teaching and administrative duties without needing to apply for the large grants that are now a staple of research systems, particularly in high-income countries. With greater public funding has come more scrutiny from policymakers and funders, and more desire to show some form of return on investment.

That is right and proper: no one wants to see taxpayers’ monies being misspent. But world-changing discoveries often occur unexpectedly and are built on years — or decades — of fundamental research that expanded our knowledge of the world and how it works. And because private companies are constrained by the need to provide returns in the short term, they rarely provide the sort of consistent, long-term funding needed for the fundamental research that finds things we didn’t know we were looking for.

All governments need to make choices about how best to spend public money. In the case of research, that necessitates working with the research community to adjust the balance of funding to different fields, cutting finance to some and increasing the pot for others. But before those decisions are made, two myths should be dispelled: that fundamental science is less important than other types of research, and that it has no long-term impact. The discoveries described in our News Feature are a timely and necessary reminder that funding decisions should not neglect the painstaking, long-term studies that have proved, time and time again, to be foundational to knowledge, progress and, ultimately, the betterment of society.