Sex between Aedes aegypti mosquitoes lasts about 14 seconds.Credit: Jacopo Razzauti/The Rockefeller University

Female mosquitoes that transmit dengue and other diseases are actually in charge during sex, according to a study1 that challenges the long-held view that they are passive participants.

Mosquito blood meals reveal history of human infections

Leslie Vosshall, a neurobiologist at the Rockefeller University in New York City, and her team were intrigued by the observation that male mosquitoes of the Aedes genus seem to pursue females constantly, yet females typically mate only once in their lifetimes. “The question was: how are the females able to say no?” Vosshall says.

Using fluorescent sperm and some careful camera work, the researchers showed for the first time that, when a male Aedes mosquito initiates contact, the female extends the tip of her genitals by a fraction of a millimetre — roughly the thickness of a human fingernail. If the female does not give this subtle, but crucial, signal, the male’s efforts fail, and copulation does not occur.

Mosquito sex lasts only a few seconds, and usually occurs in mid-air. These factors, combined with the minute size of the genitals, have made it difficult to study exactly what’s going on, Vosshall says, adding that the scientists who previously studied mosquito breeding probably just shrugged and said, “Yeah, the male is in charge.” Her team’s findings, which could have implications for controlling disease-carrying mosquitoes, were published today in the journal Current Biology1.

Fluorescent sperm

To study the intricate mating process of Aedes aegypti — the main species of mosquito that transmits dengue — Vosshall and colleagues first engineered transgenic males that produce either green or red fluorescent sperm. Then they put some of each type into a cage with females of the same species for seven days. When the females were dissected at the end of that period, more than 90% of them had sperm of only one colour stored in their bodies, supporting the idea that they mate only once in their lifetime.

In a second set of experiments, the team filmed the mating process using an elaborate set-up. The researchers glued a female mosquito to a metal pin, so that she could move her wings and legs but not fly away, like a trapeze artist in a rigid tether. They then introduced free-flying males into the cage, and recorded the interactions between the male and female genitals at high resolution.

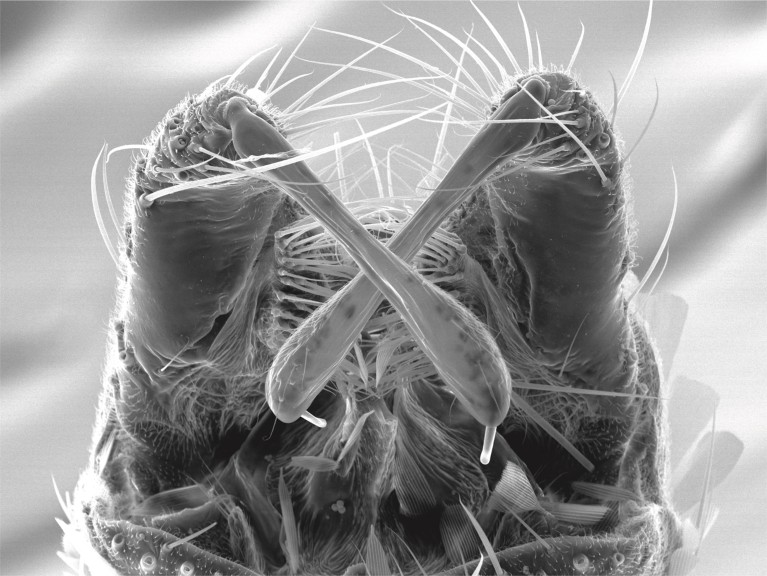

Male Aedes mosquitoes use drumstick-like genital structures called gonostyli (shown here, crossed) to tap on the genitalia of females when initiating sex.Credit: H. Amalia Pasolli, Anurag Sharma/The Rockefeller University

Leah Houri-Zeevi, a researcher in Vosshall’s lab, spent hundreds of hours looking at the videos, frame by frame. She noticed that when a male is trying to copulate, he doesn’t simply extend his sex organ — the equivalent of a penis — towards the female. Instead, he first taps the female genitalia with drumstick-like structures called gonostyli. In response to the tapping, a virgin female might elongate the tip of her genitalia, to enable copulation. Houri-Zeevi noticed that non-virgin females, however, typically kept their genitals retracted, blocking further mating attempts.