In 2022, neurosurgery researcher René Aquarius and Kim Wever, his colleague at Radboud University Medical Center and an expert in systematic reviews of animal studies, were about to embark on a literature review project when they noticed several odd things that made them stop in their tracks, then change the course of their study entirely.

René Aquarius is a neurosurgery researcher at Radboud University Medical Center. He seeks better treatment options for patients with brain conditions such as hemorrhagic stroke.

René Aquarius

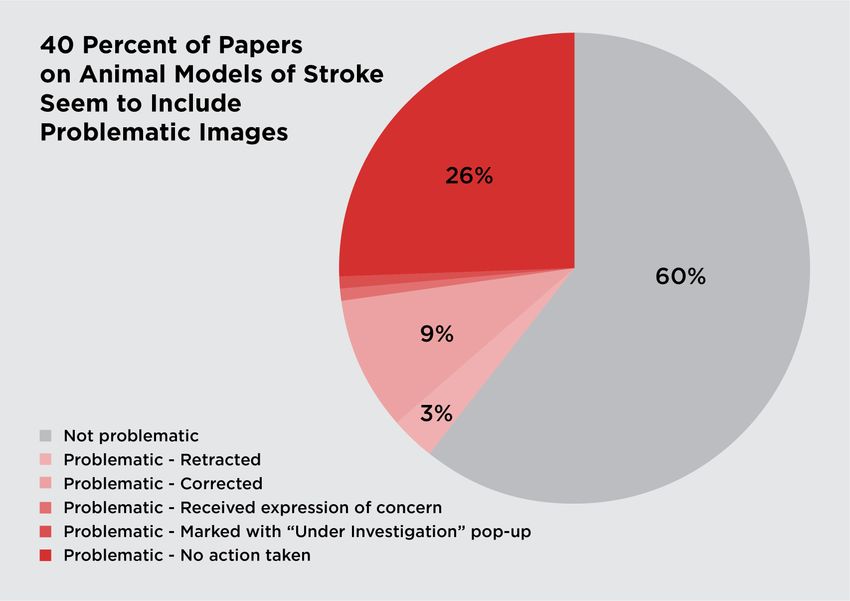

Aquarius had planned to review animal models of subarachnoid hemorrhage, a type of stroke, in hopes of finding better treatments for human patients. But he and Wever instead ended up investigating how many papers on the topic were likely questionable because they contained problematic images. In a recent study, published in PLoS Biology, the researchers found an answer: about 40 percent of them, and this is likely an underestimate.1

To Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist and scientific integrity consultant, the study was a clear example of how problematic images could directly hinder scientists’ work and the progression of science. “They couldn’t even do their originally planned work. They had to completely revise it because it turned out that most of the papers they found might have been fraudulent,” said Bik, who was not involved in the study.

During one of their first meetings to discuss the project, Wever asked Aquarius how many papers he expected to find on animal models of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Aquarius said about 50—they found 600.

40 percent of studies on subarachnoid hemorrhage, a type of stroke, using animal models likely have image issues, a new study reports. For about 65 percent of these studies, publishers had taken no action to retract, correct, or mark the studies.

The Scientist

Wever reflected on her experience with dozens of other researchers whom she had supported with systematic reviews. She thought that the vast discrepancy was strange “because experts on content don’t underestimate the number of papers by that extent.”

Kim Wever provides methodological support to other researchers at Radboud University Medical Center in performing systematic reviews of animal studies.

Kim Wever

At first, Wever shared, she and Aquarius were excited by all the evidence that they had not expected to exist. But they soon became alarmed when they noticed that specific drugs or therapies that looked promising were reported “only once and never again,” said Wever.

Wever said, “I’ve worked on many of these projects, and that never really happens.” In most cases, she explained, when scientists find promising results from an animal study, they would perform another, and then they or others would try to translate the work into the clinic. “That was when we were like, ‘Okay, stop. We should investigate what’s going on here.’”

Both Wever and Aquarius had attended one of Bik’s lectures a few years before where she had discussed image duplications and manipulations in scientific papers. They have since followed Bik’s X account, on which she regularly posts potentially problematic images from scientific papers under the hashtag “ImageForensics.”

“We thought that if these papers were not what we expected to find, maybe [image problems] would be a place to start,” Wever said. The team very quickly discovered that this indeed seemed to be the case, so they decided to change their original research question and delve into the issue.

“The pivot was very strange,” Aquarius said. “I have never experienced a pivot like this at all in any project that I have ever done.”

For the study, Aquarius, Wever, and their colleagues searched research databases (Medline and EMBASE) for full-length research articles on animal models of subarachnoid hemorrhage. After removing duplicates and screening the paper titles and abstracts to ensure that they fit the search criteria, the researchers ended up with 608 studies to evaluate.

At first, the team looked for problematic images by eye, but they later employed an AI tool called Imagetwin, which can detect the duplication of images or parts of images. The researchers used the software to help automate their investigation, but they still manually checked the flagged studies and only marked them as problematic if they agreed with the tool’s assessment.

Out of the 608 studies, they found that 250 were suspicious due to image duplication-related issues. From these, they ended up excluding seven after further investigation; for example, some authors sent their raw images and upon evaluating these images, the researchers deduced that the issue likely arose because publishers altered insignificant parts of the images for stylistic purposes. This meant that 243 of 608 studies were problematic.

“The problems they found have to be the tip of the iceberg,” Bik said, noting that image issues are not limited to duplications and that there are “many ways to cheat that would not leave traces.” For this reason, Bik agreed with the study authors that the proportion of problematic studies they reported is likely an underestimate. “That is pretty scary,” she said.

Elisabeth Bik is a microbiologist and a research integrity consultant. Her sleuthing of image manipulations in scientific papers helped inspired Aquarius and Wever’s work. She was not involved in the study.

Michel N Co

Aquarius flagged the problematic studies on PubPeer, a site containing published, peer-reviewed articles which, according to Wever, was initially intended to be a journal club platform but “has now become a place where people report concerns about potential research misconduct,” she added.

Despite this, Aquarius discovered that others had identified only five studies out of the 243 as potentially problematic. But even after Aquarius flagged the other articles on PubPeer, for about 65 percent of these studies, the publishers had taken no action to correct, retract, or mark them on their site.

“Publishers are not really doing much,” Bik said, calling for a change. “We need more of these investigations, but it needs to be done by the publishers much earlier in the process of publishing, not by researchers who stumble on these things.”

Bik also emphasized that while the issue is serious, “it doesn’t mean that science as a whole is bad. That will be an enormous extrapolation.”

Wever hopes that such checks will be implemented in the standard workflow of systematic reviews of animal studies. She and Aquarius are also working together to see if they find the same issues in other fields.

Aquarius is “just really curious on how the field will respond,” he said. “I want to see what happens first because this is just horrible.”