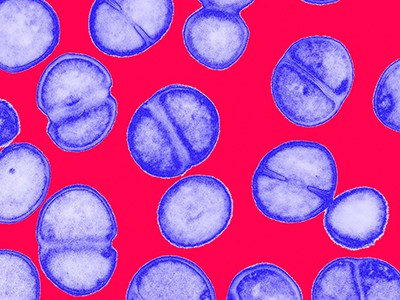

A colony of Streptomyces coelicolor bacteria secretes an antibiotic compound (red) into the surrounding medium.Credit: Dr Jeremy Burgess/Science Photo Library

By studying the process through which a soil bacterium naturally produces a well-known drug, scientists have discovered a powerful antibiotic that could help to fight drug-resistant infections.

In experiments described in the Journal of the American Chemical Society on Monday1, the team studied the multi-step pathway that the bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor uses to make the antibiotic methylenomycin A, which was first identified in 19652,3. They discovered an intermediate compound — called premethylenomycin C lactone — whose antimicrobial activity was 100 times stronger than that of the final product. Tiny doses of it killed strains of bacteria known to cause hard-to-treat infections.

Five ways science is tackling the antibiotic resistance crisis

The discovery was a ‘surprise’, says study co-author Gregory Challis, a chemical biologist at the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK. “As humans, we anticipate that evolution perfects the end product, and so you’d expect the final molecule to be the best antibiotic, and the intermediates to be less potent,” he says. But the finding “is a great example of what a ‘blind watchmaker’ evolution is. And it’s a good way of exemplifying it in a very molecular way,” adds Challis.

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing threat, projected to cause 39 million deaths worldwide over the next 25 years. Researchers say that the discovery of a potent antimicrobial compound might lead to fresh drugs to tackle resistance.

The work underscores “the potential of such studies to identify new bioactive chemical scaffolds from ‘old’ pathways”, says Gerard Wright, a biochemist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Accidental discovery

In 2006, Challis and his colleagues began studying the molecular pathway through which Streptomyces coelicolor produces methylenomycin A. To do this, they deleted the genes encoding enzymes involved in each step, one by one. Their work built on earlier efforts in 2002 to sequence the bacterium’s genome4.

New antibiotic that kills drug-resistant bacteria discovered in technician’s garden

By 2010, the team had mapped the mechanism that the bacterium used to make methylenomycin A and identified several intermediate molecules that it produced along the way.

“We were just doing very fundamental blue-sky research,” says Challis. “We discovered these intermediates, and we left them for a while because we didn’t quite know what to do with them.”

It was several years later — around 2017 — that a PhD student at Challis’s laboratory tested these intermediate molecules for antimicrobial activity.

These tests revealed that two molecules, including premethylenomycin C lactone, were much more effective than methylenomycin A at targeting seven strains of Gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, which infects skin, blood and internal organs, and Enterococcus faecium, which can cause deadly bloodstream and urinary infections.

The lowest concentration of premethylenomycin C lactone needed to kill drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus was just 1 microgram per millilitre, compared with 256 micrograms per millilitre of methylenomycin A. The compound could also kill bacteria at much smaller doses than those needed for vancomycin, a ‘last line’ antibiotic used to treat infections caused by two Enterococcus faecium strains, to be effective.