The first-ever cellular atlas of the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which transmits more diseases than any other species of its kind, has been created. The Mosquito Cell Atlas provides cellular-level resolution of gene expression in every mosquito tissue, from the antennae down to the legs.

The atlas was recently published in Cell in the paper, “A single-nucleus transcriptomic atlas of the adult Aedes aegypti mosquito.”

“This is a comprehensive snapshot of what every cell in the mosquito is doing as far as expressing genes,” says Leslie Vosshall, PhD, professor at The Rockefeller University and vice president and CSO at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “It’s a real achievement because we profiled so many different types of tissues in both males and females.”

Most prior work building mosquito atlases has focused on female mosquitoes, leaving out males. “Because the female is the one that’s spreading all the pathogens, there is an enormous bias toward looking at the biology of the female and very little information about the male,” Vosshall notes. “So we wanted to be inclusive and fill in the gap.”

The atlas yielded new insights including identifying novel cell types and expanding the understanding of sensory neuron organization of chemoreceptors across all sensory tissues. Also, the work uncovers differences—and unexpected similarities—between male and female mosquitoes including the changes in genetic expression that the female mosquito brain undergoes after a blood feeding.

More specifically, the atlas revealed male-specific cells and sexually dimorphic gene expression in the antenna and brain. In female mosquitoes, the researchers found that “glial cells, rather than neurons, undergo the most extensive transcriptional changes in the brain following blood feeding.”

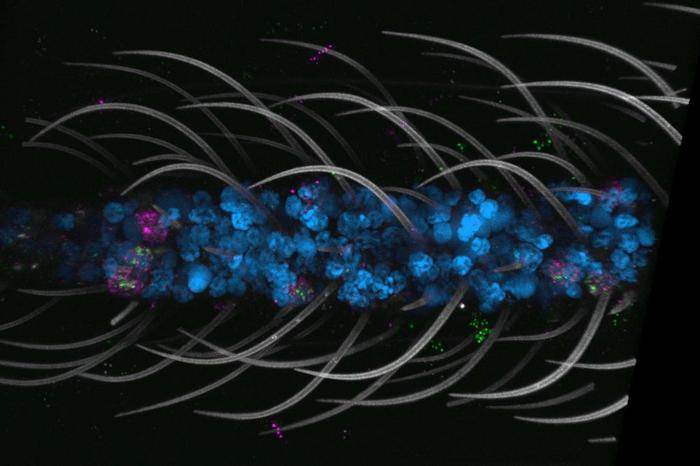

The team used single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) to create a large dataset of more than 367,000 nuclei from 19 types of mosquito tissues selected across five biological themes: major body segments; sensation and host seeking; viral infection; reproduction; and the central nervous system. They found 69 cell types grouped into 14 major cell categories, many of which had never been seen before.

Among the most striking findings was the pervasiveness of polymodal sensory neurons. Previous research from the Vosshall lab had found that the antenna and maxillary palps were packed with these neurons, but now that they were able to look organism-wide, they found them everywhere, including the nose, tongue, and legs.

Brain changes, behavior shifts

After feeding, a female mosquito loses all interest in humans and other hosts; her focus becomes developing and laying eggs.

“How does this incredibly strong drive to bite people get turned off?” Vosshall says.

To find out, the team examined the gene expression of female mosquito brains at 3, 12, 24, and 48 hours after a blood feeding. They found changes in gene expression in all time periods, which peaked after the first few hours and gradually abated. Most of the early expression changes were of genes being upregulated, while later time periods showed a mix of both up- and downregulation.

Although neurons account for roughly 90% of mosquito brain cells, it was the glia—support cells that account for less than 10%—that underwent large shifts in gene expression.

“The glia are completely rewired during this time when the females lose interest in people,” Vosshall says.

The team also found that female and male mosquitoes’ cellular makeup is largely identical, aside from small clusters of sex-specific cells and reproductive organs. One exception was found exclusively in the male antenna, which is largely unexplored. “A small group of cells is marked by the expression of a single gene that’s not expressed in any female tissue,” Vosshall says. “If we hadn’t compared male and female gene expression, we never would’ve spotted them.” Their function remains to be determined.

“This is a global resource that has been open to everyone since the very inception of the project in 2021, so many people are already using it,” Vosshall adds. “We’re excited to see the discoveries that will come from it.”

The dataset is freely available to all researchers.