When the world’s nations meet for COP30 in Belém, Brazil, on 10 November to lock down new commitments to limit dangerous climate change, it will be the first such conference since US President Donald Trump announced in January that his country would, for the second time, exit the landmark Paris climate treaty.

Drill, baby drill? Trump policies will hurt climate ― but US green transition is underway

Trump and his administration have championed fossil fuels, called climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world” and rolled back federal funding and tax breaks for clean energy introduced under former president Joe Biden.

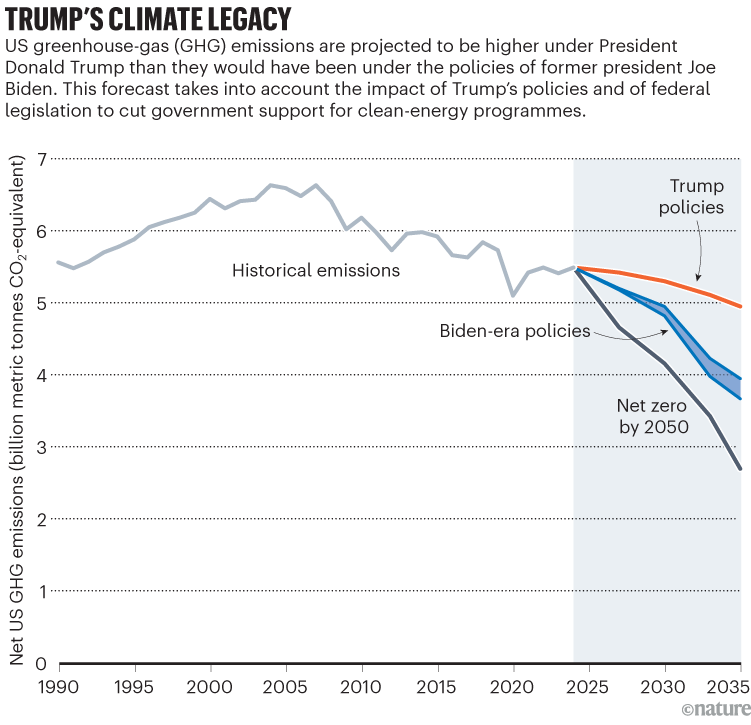

The United States is the world’s second biggest greenhouse-gas emitter, accounting for 11% of global emissions. Although US emissions will continue to fall under Trump, they could increase by up to 470 million tonnes annually — more than three times the annual total from the Netherlands — over the next decade compared with what they would have been under Biden policies, according to an analysis led by researchers at Princeton University in New Jersey (J. Jenkins et al. Preprint at Zenodo https://doi.org/qbrm; 2025; see ‘Trump’s climate legacy’).

Source: Repeat Project

The US exit from the Paris accord will not become official until January 2026. Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva explicitly invited Trump to COP30. But the Trump administration is not expected to send any high-level representatives to the meeting, and many say that’s for the best. “Without the US, there’s still a chance the world could come together in Belém,” says Claudio Angelo, the international policy coordinator at Observatório do Clima, a coalition of climate organizations, who is based in Brasília.

Whether that happens, and so whether humanity bends the emissions curve sufficiently to escape the most dangerous climate impacts, depends in large part on the actions of other big players. China is the world’s largest greenhouse-gas emitter, accounting for nearly one-third of the global total — and it is also the global leader in renewable energy. India and the European Union come after the United States, at 8% and 6 % of emissions, respectively. Brazil is expected to take on a bigger climate leadership role as host to COP30 and home to the Amazon, a major carbon sink. US states and cities are also pursuing their own clean-energy agendas. COP30, at which countries are expected to agree a round of more-aggressive climate targets, offers a glimpse of these actors’ plans.

Will China take the lead on climate?

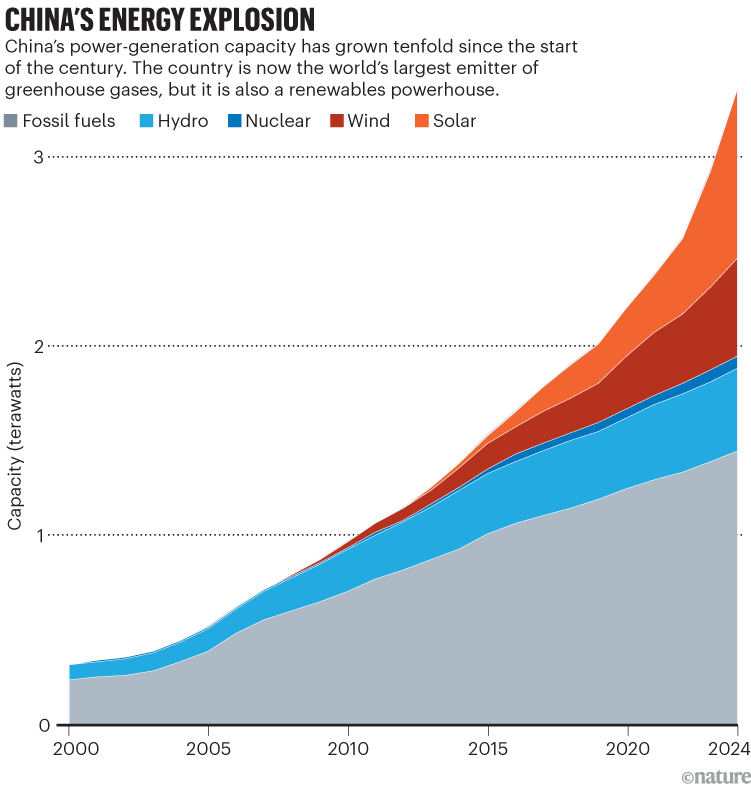

In addition to being the world’s largest emitter, China has driven 90% of the growth in carbon dioxide emissions since 2015, the year the Paris agreement was adopted. But the country also leads the world when it comes to adopting clean energy and producing the equipment needed for the transition to a decarbonized economy, including solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles (see ‘China’s energy explosion’).

Source: China Statistical Yearbook, China Electricity Council & Natl Energy Administration

In September, China’s President Xi Jinping announced plans to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 7–10% from ‘peak levels’ by 2035. Although some say Beijing’s proposition falls short of expectations, as well as short of what is needed to prevent catastrophic climate change, others argue that it is compatible with the Paris treaty.

Whether Washington’s climate U-turn affected China’s targets is hard to tell. Yao Zhe, a Beijing-based researcher at Greenpeace East Asia, suspects that it might have “demotivated” China to set higher targets, by lowering the bar for what was needed to look ambitious. But a more pressing factor, she says, is the country’s slower-than-expected economic growth since the COVID-19 pandemic, which has pushed policymakers to prioritize the economy over environmental and climate goals. And if the economy rebounds, then emissions could too.

That Xi personally announced China’s latest climate targets signals a “very high-level commitment” to tackling climate change, says Belinda Schäpe, a China analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a think tank in Helsinki. And it is actions — not projections — that matter. “Until now, China has a track record of overperforming on most of its climate commitments,” says Hu Min, co-founder of the Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based think tank.

Trump will weaken climate action — the rest of the US must not follow suit

China is unlikely to step straight into the leadership vacuum left by the United States because the countries have different statuses under the Paris agreement, Schäpe says. Developed countries are expected to take the lead in cutting emissions, but China is classed as a developing country under the treaty.

Another challenge for China when it comes to leading on climate is that it is still building coal-fired power plants. In 2024, the country was home to more than 90% of the coal-power capacity that broke ground around the world. The plan is to use the new facilities as back-ups for unpredictable renewable power. But analysts warn that the world might find it hard to accept a climate leader that is still expanding its coal programme.

China could lead at COP30 by using its influence among developing countries to facilitate negotiations with developed ones, says Kim Vender, who researches China’s environmental governance at the Centre for EU-Asia Connectivity in Bochum, Germany. Many predict that China will work with Brazil to secure more money for developing countries’ efforts to mitigate climate-change impacts. Beijing has endorsed a Brazil-led finance programme aimed at preserving tropical forests, set to be launched in Belém.

With the US federal government absent, China will have greater influence over global climate governance at COP30, but the world should expect leadership of a different flavour, says Yao. “They cannot expect China to do exactly what the US or other developed countries do.”

Brazil’s net-zero potential

As host of COP30, Brazil’s role is to serve as a neutral facilitator of negotiations: the government says it will “lead by example” on climate. It has every reason to want to: the country is at risk of severe consequences from climate change, as demonstrated by devastating floods in 2024 that displaced 500,000 and killed 185 people.

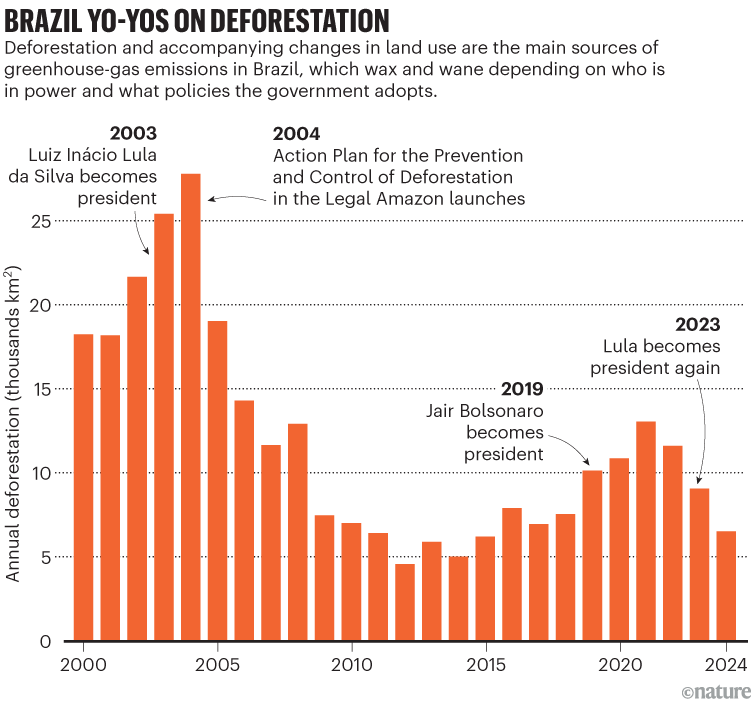

One area where Brazil is well placed to lead in emissions reduction is by tackling deforestation. Forests act as sinks that remove carbon from the air; their destruction releases carbon and often paves the way for emissions-intensive agriculture. In Brazil, which is home to 60% of the Amazon — the world’s largest tropical rainforest — deforestation and agriculture drive the most emissions of any sector.

Deforestation in the Amazon surged under former president Jair Bolsonaro (see ‘Brazil yo-yos on deforestation’) and reversing the trend “is not simple”, says Thelma Krug, coordinator of the scientific council for COP30, who is based in São José dos Campos.

Source: Natl Inst. for Space Research (INPE), Brazil

In September, Lula announced a US$1-billion investment in the Tropical Forests Forever Facility, a fund that will pay countries to protect endangered forests. “It would pay for something that has never been recognized: the effort developing countries make to keep parts of their territory intact,” says Krug. At COP30, Lula hopes to secure more contributions to the fund.

On other commitments to slash emissions, Brazil could find it harder to lead by example. Its latest targets, announced in November 2024, have been criticized as not ambitious enough. Certain sectors of the Brazilian government still support projects that could drive up emissions, such as a highway cutting through the Amazon and oil drilling at the mouth of the Amazon River.

But the country still has great potential for decisive action, says Philip Fearnside, an ecologist at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus. He thinks that deforestation is still relatively straightforward to tackle, because it contributes little to Brazil’s economy. Although deforestation supports certain industries, halting it entirely would cause only a small dip in the country’s gross domestic product, according to a 2017 analysis (see go.nature.com/472midv) coordinated by Instituto Escolhas, a sustainability think tank in São Paulo. And Brazil has thousands of kilometres of coastline suitable for wind power and ideal conditions for solar farms. Fearnside describes it as “one of the countries that has the easiest options for actually achieving zero emissions”.

Brazil will invest US$1 billion in a fund to protect tropical forests such as the Amazon.Credit: Pablo Porciuncula/AFP/Getty

India motors on climate goals

India is charging ahead on its climate commitments under the Paris climate treaty. In June, its government announced that 50% of installed electricity generation capacity now comes from non-fossil-fuel sources — a milestone that was reached five years ahead of the 2030 deadline the nation had set.

The achievement is part of broader progress towards the nation’s goal under the Paris agreement, which the US exit seems unlikely to dent. That’s because India will continue with its decarbonization agenda for the sake of its own energy security, says Rajani Ranjan Rashmi, a climate-policy researcher at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in New Delhi. Self-reliant economic growth has been central to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s governance — and to achieve that, India needs renewables such as wind and solar.

Will US science survive Trump 2.0?

What’s more, although India tied reducing its dependence on fossil fuels to funding from developed nations, it has made progress on that goal even though much of the cash has not materialized. “Ultimately, every large emerging country has to plan for itself,” says Rashmi.

Alongside its expansion in renewables, India is heavily reliant on coal and is still building new capacity. The country, a developing nation under the Paris agreement, has argued that it needs the highly polluting fuel to power its economy and lift the population out of poverty, and that it doesn’t need to give up coal in the short term, given that its per capita emissions, and historic emissions, are low compared with those of developed nations. But, in 2025, a surge in power from renewable sources began to replace coal-powered energy in India.

The actions of the US federal government could still disrupt India’s decarbonization efforts. India is expected to submit revised targets at COP30, but whether these will be even more ambitious than its current ones will depend on “global signals”, says Rashmi.

The Trump administration’s disruption of global trade could affect the climate priorities of developing nations, including India. “Trump 2.0 is wielding a lot of economic weapons to subjugate trade partners and countries around the world,” says Avantika Goswami, a climate-policy researcher at the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi. Such pressure can shift the priorities of developing nations away from decarbonizing to, for example, building economic resilience or diversifying their trade partners, she says.