“The first time I saw a chamois, a mammal closely related to both goats and antelopes, was more than 40 years ago while I was hiking in Epirus, a mountainous region in western Greece. Chamois were rare then; the desire to learn about and protect them inspired me to become a biologist. Over the past 25 years, their population in my study area — the Northern Pindos National Park — has grown drastically, mainly thanks to a ‘human shield’ effect created by hikers visiting the upper parts of the Northern Pindos mountain range: their presence has made poaching more difficult.

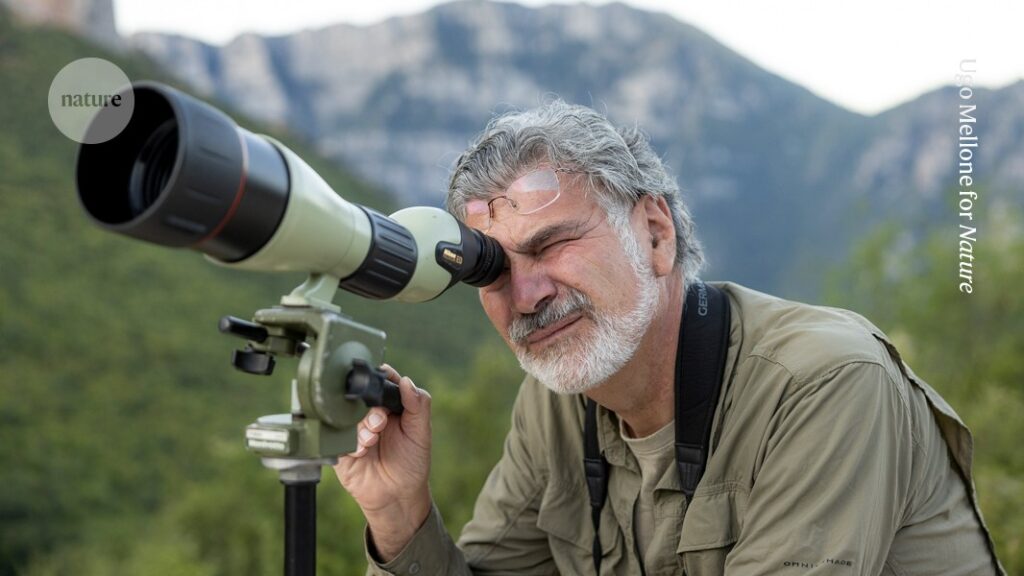

Now, I can easily see dozens of Balkan chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra balcanica) just a few hours from my village. In this picture, I’m counting them on the ledges of a cliff, one of their favourite habitats. We think that there are now around 1,000 individuals in the national park and nearby mountain ranges.

Studying chamois requires the skills of a mountaineer and a scientist’s precision. My colleagues and I have built a habitat suitability model, based on elevation, vegetation, slope and human activity, and are testing it by checking for chamois presence in areas across northern and central Greece. We have discovered small populations in those areas and are in the process of defining wildlife corridors and identifying threats to those populations.