Differences in brain regions and metabolism influence people—and animals’—drinking habits, which affect the body over the long term. A better understanding of this could lead to the development of therapies for alcohol use disorder.

As the holiday season arrives with its traditions of reunions and parties, glasses clink a little more than usual, with people leaning into celebration and long-awaited breaks. Whether it is humans treating themselves to one too many glasses of wine, animals seeking out fermented fruit, or researchers getting mice drunk, alcohol shapes behavior in surprising ways. Indulge in this article to find out the effects of alcohol and what they tell us about biology.

Even though pen-tailed shrews perennially feed on alcoholic palm nectar, the animals do not appear intoxicated, suggesting that they have mechanisms to help them efficiently metabolize ethanol. Matthew Carrigan, who studies the evolution of alcohol metabolism at the College of Central Florida, believes that there may be evolutionary advantages to having a high alcohol tolerance, especially for animals that regularly consume fermented fruit and its nectar. Consistent with this, when Carrigan and his colleagues compared the gene encoding an alcohol metabolizing enzyme between modern animals and their ancestors, they found a mutation enabling modern animals to metabolize ethanol nearly 40 times faster than their ancestors. Without this ability, animals would likely stumble around the jungle in an intoxicated state with predators looming nearby, which is a less-than-ideal scenario.

Binge alcohol consumption in mice activated only a few neurons (red) in the medial orbitofrontal cortex. Cells stained blue depict neurons insensitive to alcohol.

Gilles Martin Lab

Using brain scans, scientists identified brain regions underlying binge alcohol drinking, but the specific neuronal circuits involved remain poorly understood. To investigate these, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School neurobiologist and electrophysiologist Gilles Martin and his team exposed mice to alcohol and carried out patch clamp electrophysiology experiments to measure neuronal activation. They uncovered neuronal ensembles, or cell populations with coordinated activity, in specific brain regions, recruited in response to binge drinking. These cells make up a very small fraction of the total neurons in the specific brain areas, laying the foundation to leverage the unique neuronal fingerprint to suppress and treat binge alcohol drinking.

While the gut-brain axis, the bidirectional connection between the gut microbiome and the brain, is well known, much of the work focuses on only part of the microbiota: bacteria. Scientists had found higher levels of a common fungus, Candida albicans, in the fecal microbiome of people with alcohol abuse disorder, but the fungus’s influence on alcohol consumption remained unknown. Carol Kumamoto, a microbiologist at Tufts University, and her team found that mice colonized with C. albicans indulged in less alcohol compared to animals unexposed to the fungus. Mechanistically, C. albicans increased levels of a circulatory inflammatory marker that reduced the animals’ desire for alcohol, offering potential new treatment strategies for alcohol use disorder.

Some people may be complete teetotalers, while some others can indulge in a glass of wine or even multiple shots of pure spirits before losing control. In addition to body size and sex, genetics influences how drunk someone gets. Mutations in the alcohol metabolizing genes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) alter how fast alcohol breaks down within the body. In addition to genetics of metabolism, differences in the cerebellum, the brain region involved in motor function and balance, can influence how wobbly one gets after drinking. David Rossi, a molecular neuroscientist at Washington State University, compared mice with higher ADH and ALDH to less tolerant rodents. He found that the sensitivities of GABA receptors, which reduce neuronal firing upon stimulation leading to sluggish movements, differed in both groups of animals.

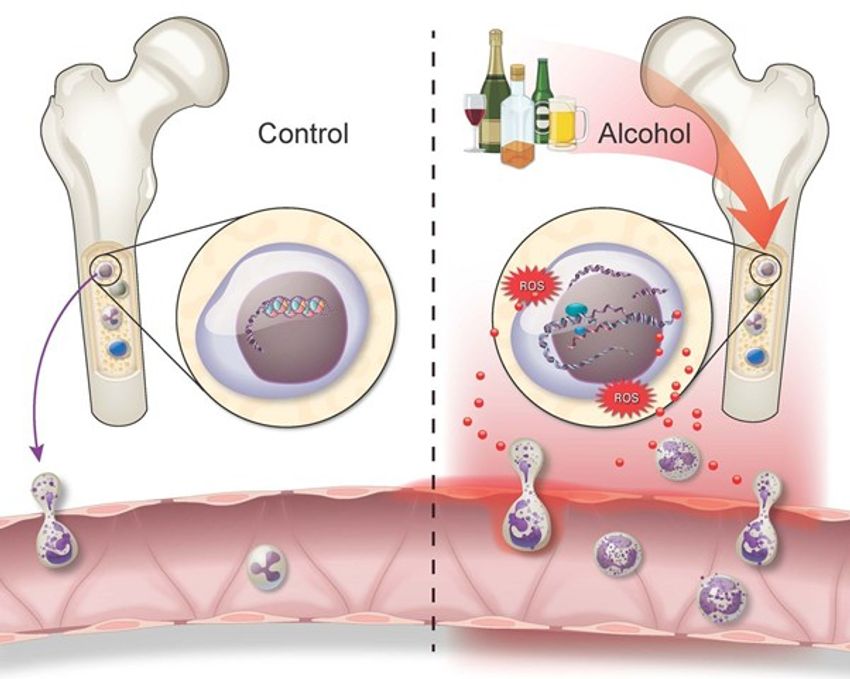

Alcohol induces inflammatory changes in immune stem cell progenitors in the bone marrow that may last even after drinking stops.

Matt Hazard and Thomas Dolan with BioRender.

Chronic alcohol consumption impairs immune cell production and function. To investigate the long-term effects of alcohol on the immune system, University of Kentucky immunologist Ilhem Messaoudi and her team studied rhesus macaques who voluntarily drank high levels of alcohol for a year. The researchers isolated bone marrow cells from the animals and observed that in vitro, differentiated progenitor cells skewed toward “neutrophil-like” monocytes with higher inflammatory gene and cytokine expression. These findings could be crucial when developing treatments for people with alcohol use disorders.

While those who drink alcohol are more susceptible to cardiovascular diseases, many believe that this only applied to heavy drinkers. Takahiro Suzuki, a physician at St. Luke’s International Hospital, sought to understand the health impacts of occasional alcohol consumption, defined as an average of one or two drinks per day. Analyzing data from more than 58,000 people gathered over a decade of health checkups, his team found a slight spike in the blood pressure of those who started drinking occasionally. There was no difference between those who drank beer, wine, or spirits, suggesting that alcohol quantity, and not its composition, drove the blood pressure changes. Conversely, people who gave up drinking showed lower blood pressure. The findings indicate that contrary to popular belief, an occasional drink may actually be harmful in the long run.