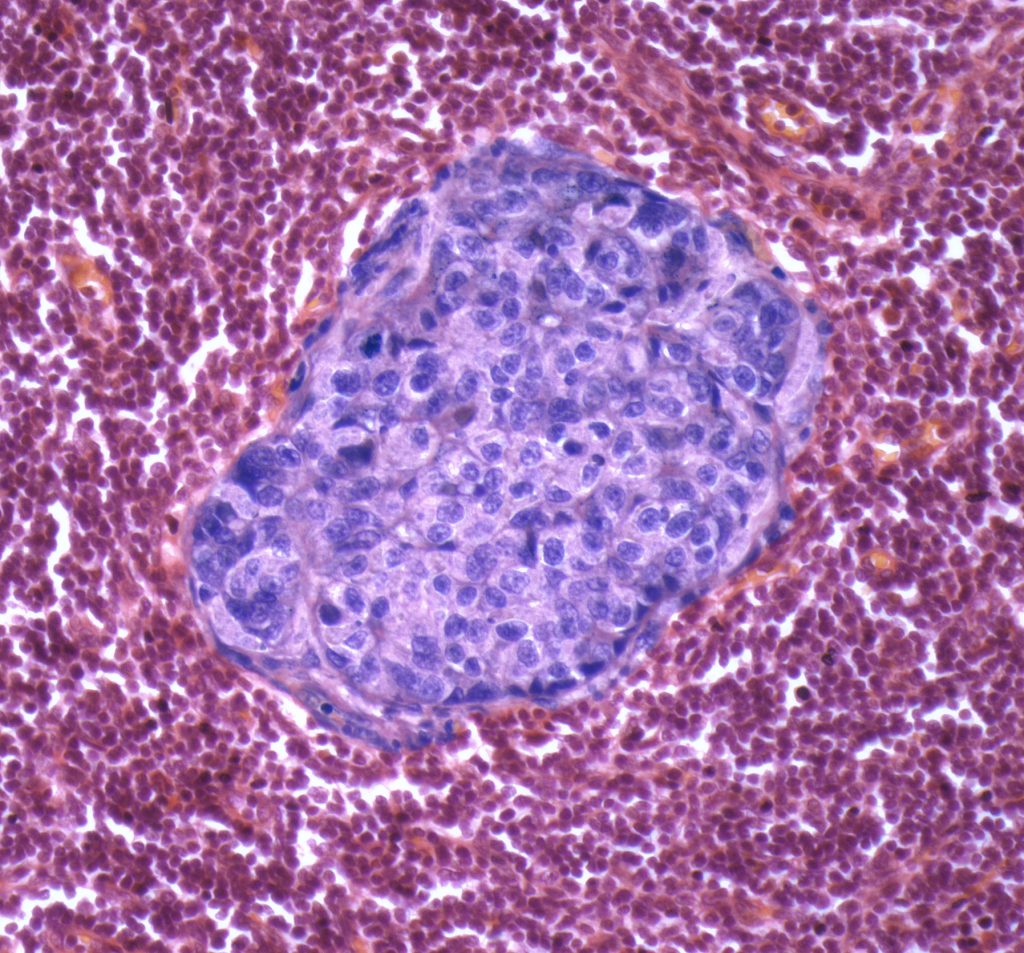

University of Cambridge researchers have developed a machine learning algorithm that facilitates accurate spatial quantification of tumor tissue on digital pathology images, potentially enabling personalized treatment decisions guided by both what the tumor looks like and what its biology reveals.

The tool, named SMMILe (Superpatch-based Measurable Multiple Instance Learning), not only matches or exceeds the performance of current state-of-the-art whole-slide image (WSI) tissue classification tools for the detection of cancer cells in tumor biopsies and surgical sections, but also predicts where the tumor lesions are located and the proportion of regions with different levels of aggressiveness.

“SMMILe stands out because it delivers precise, scene-aware quantification of tissue types across diverse pathological contexts,” said lead researcher Zeyu Gao, PhD, from the Department of Oncology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K.

“Rather than simply classifying a slide, it is able to measure how different tumor subtypes, grades and surrounding tissue components are spatially organized, giving us a structured and truly quantitative view of the tissue,” he told Inside Precision Medicine.

Writing in Nature Cancer, Gao and co-authors explain that spatial quantification is a critical step in most computational pathology tasks because it guides pathologists to areas of clinical interest, can be used in biomarker discovery, and may facilitate downstream tasks such as spatially resolved sequencing.

Yet the development of spatially aware computational pathology models is limited by the need for detailed spatial annotations, which are often unfeasible due to the vast scale of gigapixel images and the need for specialized domain knowledge.

To overcome the need for manual annotations, modern computational pathology tools have use multiple-instance learning approaches that take a “representation-based” approach. They extract features from many small regions of a slide and then use an attention mechanism to combine these features. This allows the model to make predictions for the whole slide while also highlighting which regions are most important.

These models have been successfully used in cancer screening and diagnosis, and for finding molecular markers and predicting treatment response. But the attention maps they produce can only be interpreted by visually inspecting them, which is qualitative and increasingly considered suboptimal for making spatially precise predictions.

To address this, Gao and team developed SMMILe, a WSI analysis method designed to perform spatial quantification alongside WSI classification. Importantly, the tool was trained using slides that had been given simple, patient-level diagnostic labels, such as cancer type or grade rather than needing time-consuming, detailed region-by-region annotations from pathologists.

The researchers tested the algorithm on eight datasets comprising 3850 whole-slide images covering lung, kidney, ovarian, breast, stomach, and prostate cancer. When compared with nine other WSI classification analysis AI tools, SMMILe’s performance in metastasis detection, subtyping, and grading either matched or exceeded these tools at slide-level classification, while significantly outperforming them when it came to estimating the proportions and spatial distribution of lesions.

Once the tool has been tested on real-world datasets and in multi-center prospective validation studies, Gao said he believes it could support pre- and postoperative pathology assessment, helping clinicians track tissue changes, treatment response, and risk patterns.

“SMMILe moves pathology from qualitative impressions to precise spatial quantification,” he said. “Patients who look similar under conventional pathology can now be distinguished by their tissue architecture and spatial organization. This provides a new layer of information to guide personalized therapies.”