New research maps five distinct eras of brain development, offering clinics fresh insight into cognitive aging and long-term brain health.

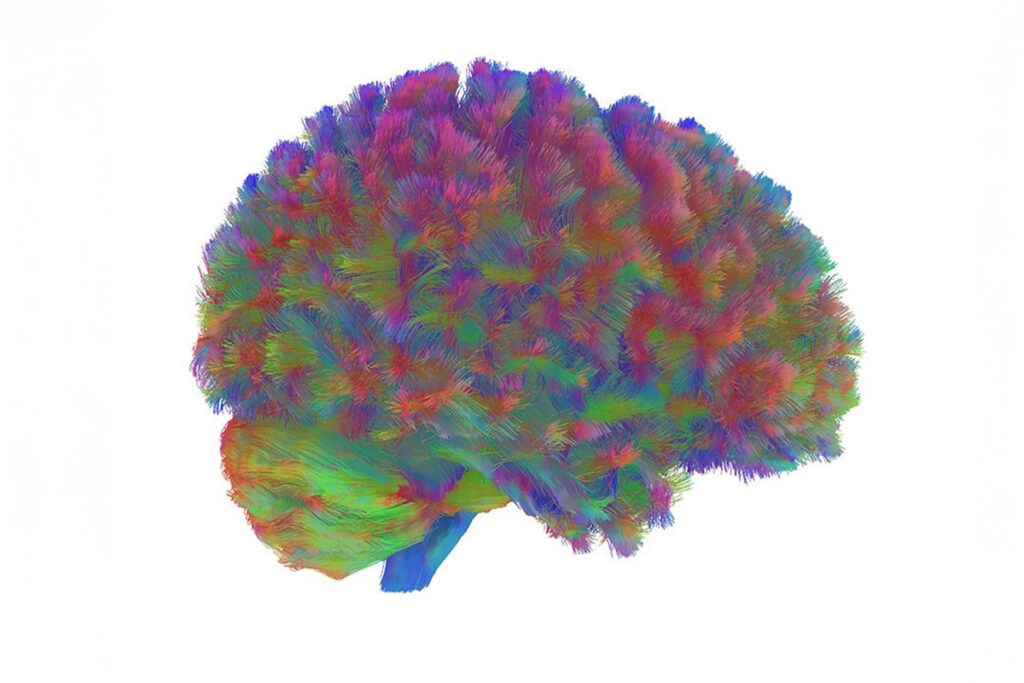

Scientists have mapped the most detailed picture yet of how the human brain changes across our entire lifetime, and the results suggest that we don’t age in a smooth curve, but in a series of distinct eras.

A large-scale study of more than 3,800 brain scans, published in Nature Communications, reveals five major phases of brain development defined by shifts in connectivity, efficiency, and network topology [1]. These turning points – at ages 9, 32, 66 and 83 – reshape how we learn, think and decline.

For longevity clinics, this is more than descriptive science. The findings offer a framework for earlier screening, precision prevention, and lifespan-based brain optimization, grounded in measurable neural transitions rather than guesswork or symptoms alone.

Era One: Foundations (Birth to age 9)

During the first decade, the brain’s network is dense and highly active. Infants display adult-like features such as modularity and “rich club” hubs, but with weaker connections. What changes in this era is not the presence of networks, but their strengthening.

By age nine, the study identifies the first central turning point: a shift from rapid foundational wiring to the start of longer-term organizational refinement. Connectivity density dips sharply during adolescence, reflecting an essential phase of neural pruning – the brain selectively removing weaker connections to improve efficiency.

For clinicians, this underscores how early-life environments, nutrition, sleep and stress shape long-term cognitive architecture far earlier than previously assumed.

Era Two: The efficiency climb (Ages 9–32)

Here, the brain undergoes a long but stable phase of reorganization. Alexa Mousley, the study’s lead author, notes that what they find suggests that “the journey from childlike brain development to this peak in the early 30s is distinct from other phases in the lifespan. [2]”

The brain becomes more integrated, communication pathways shorten, and global efficiency peaks around age 29–32.

For example, a 17-year-old and a 30-year-old don’t have identical brains, but the type of change occurring is consistent. This era sees the plateauing of personality traits and cognitive performance found in previous research.

These insights highlight why interventions such as cognitive training, aerobic fitness optimization and neuroprotective nutrition have an outsized impact in young adulthood.

Era Three: Stability with slow shift (Ages 32–66)

At roughly 32, the brain enters its longest rewiring era. Connectivity remains strong, and integration is high, but the architecture stabilizes: fewer dramatic changes, more slow reorienting of pathways.

This reflects lived experience. As co-author and Cambridge neuroinformatics professor Duncan Astle puts it: “Looking back, many of us feel our lives have been characterized by different phases. It turns out that brains also go through these eras.”

Clinically, this era represents a major window for prevention. Lifestyle, vascular health, metabolic markers and sleep quality in midlife are disproportionately influential on cognitive aging trajectories. Screening for early decline, even in asymptomatic patients, becomes essential.

Era Four: Accelerated decline (Ages 66–83)

After the mid-60s, integration falls more sharply. While total network strength continues to rise with age (individual connections become stronger), efficiency declines as pathways lengthen and redundant routes fade.

This explains why older adults may retain knowledge but struggle with processing speed or multitasking. The architecture is intact, but less optimized.

This era is where clinics see the strongest clinical justification for interventions such as:

- Anti-inflammatory and metabolic optimization

- Aerobic exercise and VO₂-max-focused programs

- Cognitive enrichment strategies

- Sleep consolidation therapy

- Nutrition targeting mitochondrial and synaptic support

Era Five: Fragile networks (83+)

The final turning point at age 83 marks a clear drop in connectivity. Networks become sparse; modularity increases; and the brain shifts into a more fragmented pattern of communication. These findings reinforce the clinical urgency of early monitoring and long-term brain longevity planning – ideally beginning decades earlier.

What this means for longevity clinics

For practitioners, the study strengthens several key messages:

- Brain aging is not linear. It unfolds in measurable epochs, each with its own vulnerabilities and intervention opportunities.

- Peak efficiency is early. Cognitive optimization strategies should begin long before symptoms.

- Midlife is decisive. It is the key phase for protecting against decline.

- Later life benefits from precision interventions. Particularly those targeting inflammation, metabolic drift and synaptic resilience.

For clinics and practitioners integrating brain-health strategies into their programs, our Longevity Clinics Directory offers evidence-based providers specializing in cognitive assessment, neuro-aging interventions and personalized longevity care.

The implications are significant. The study’s findings hint at why early intervention matters, particularly for conditions that take root in adolescence, and why treating the teenage brain as merely “immature” misses the point entirely.

Ultimately, the study adds scientific weight to something long felt but poorly explained: that adolescence leaves a biological signature. Understanding that signature – where it strengthens, where it frays, and where it can be supported – may be one of the most important steps toward improving long-term brain health.

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65974-8

[2] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/scientists-identify-five-distinct-eras-of-human-brain-aging/