Scientists refine microglia replacement as a potential therapy for neurodegenerative disease – and progress is accelerating.

Front-line innovation in neurodegenerative disease rarely arrives quickly; however, microglia replacement, once a speculative idea rooted in preclinical immunology, has crossed the translational divide with unusual speed. Five years after efficient replacement strategies were first demonstrated in mice, the same logic has been used to halt progression of adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) in human patients. The approach – known as MISTER, or microglia intervention strategy for therapy and enhancement by replacement – rests on the observation that pathogenic microglia can accelerate or even initiate disease, raising the possibility that replacing them with healthy counterparts might restore homeostasis [1].

In a Perspective published in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers behind these advances set out the trajectory of the field, the principles that enable replacement and the challenges that remain. The corresponding author, Bo Peng of Fudan University, noted the velocity of progress: “Over just five years, from 2020 to 2025, microglia replacement has evolved from its first achievement in the mouse model to successful clinical therapy [2].” That speed reflects an unusual combination of conceptual clarity, methodological refinement and translational opportunity, although the paper makes clear that such momentum will need to be matched with equally careful evaluation of safety, durability and wider applicability.

Longevity.Technology: Microglia replacement is advancing at a pace that feels almost anomalous in neurodegeneration, a field more accustomed to attrition than acceleration; moving from first demonstration in mice to clinical impact in humans within five years is unusual enough to merit both admiration and a measure of caution. The enthusiasm is understandable – microglia sit at the intersection of immunity, metabolism and neuronal health, and replacing dysfunctional populations offers a rare chance to intervene upstream of neuronal loss rather than downstream of it – yet the practicalities remain formidable. Conditioning the brain to accept donor cells requires creating temporary vacancies in regions that are not known for tolerating disruption, and although the early results in ALSP are striking, the long-term behavior of donor-derived microglia in an aging, inflamed or otherwise stressed brain is still largely speculative.

What this emerging field captures, however, is a more expansive view of how the brain ages and how it might be repaired; the neuron, long treated as the sole protagonist in neurodegenerative disease, is ceding a little ground to its immunological counterparts, and the therapeutic implications are significant. Replacement strategies hint at possibilities that sit uncomfortably close to enhancement as well as therapy – a topic likely to animate regulators as much as researchers – and scaling such approaches beyond rare monogenic diseases will demand safer, simpler routes than bone marrow conditioning. Still, microglia replacement represents a convergence of regenerative medicine and geroscience that the longevity sector has been anticipating for years, offering a reminder that sometimes the most promising routes to preserving cognition do not involve rescuing neurons at all, but reshaping the cellular environments they depend upon.

Charting the path to replacement

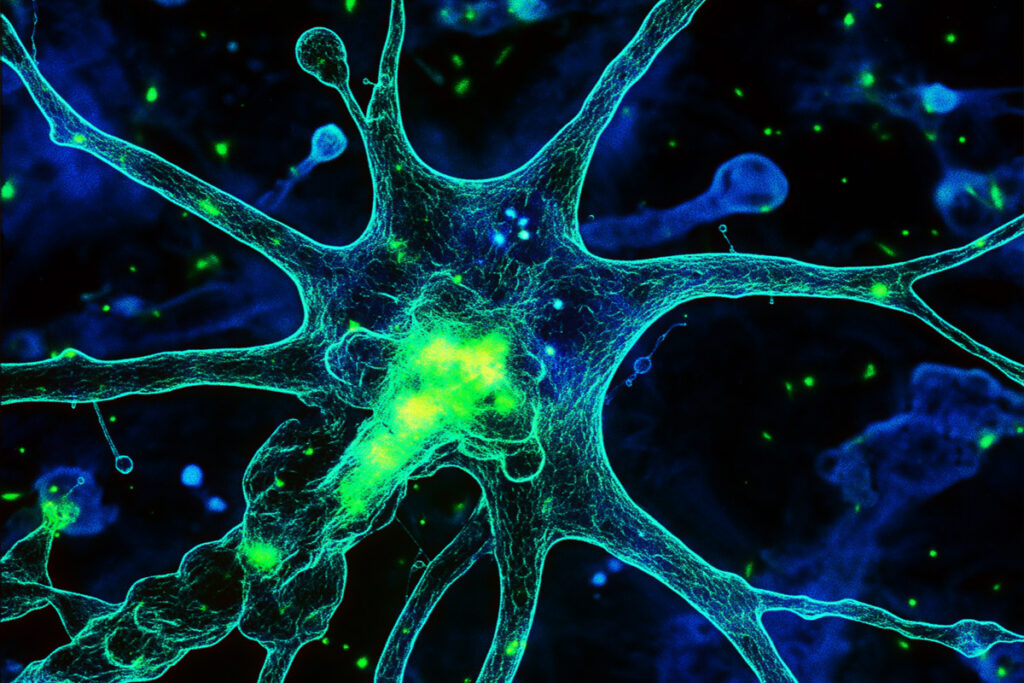

Microglia occupy a distinctive niche in the central nervous system, arising from yolk sac progenitors and maintaining their population primarily through self-renewal. When these cells acquire pathogenic mutations – in genes such as CSF1R or TREM2 – the resulting dysfunction can impair debris clearance, amplify inflammation or hasten neurodegenerative processes. In their review, the authors describe microgliopathies as both primary drivers of disease and accelerants of broader pathology, noting that “microglial gene mutations can either cause or accelerate the course of CNS disorders,” a rationale that underpins the therapeutic logic of MISTER.

Achieving meaningful replacement, however, depends on two core principles: creating a microglia-free niche in which donor cells can engraft, and suppressing the proliferation of residual host cells that would otherwise outcompete them. Conditioning regimens – ranging from irradiation to chemotherapy combinations such as Flu-Mel-ATG – help maintain this permissive environment; CSF1R inhibition, meanwhile, allows endogenous microglia to be depleted without triggering severe neuroinflammation. As the authors explain: “these approaches ablate microglia through a non-inflammatory state and do not result in severe aversive effects,” a feature that has supported regulatory acceptance of CSF1R inhibitors.

Clinical signals and conceptual refinements

The resulting engraftment can be substantial. In murine models, Mr BMT – microglia replacement by bone marrow transplantation – achieves more than 90 percent replacement in the brain, retina and spinal cord. These preclinical successes informed the first-in-human clinical attempt, in which eight individuals with ALSP received donor bone marrow following a conditioning regimen tailored to their CSF1R-deficient state. According to the team, this approach halted disease progression during a 24-month follow-up, with MRI showing structural stabilization and no further cognitive or motor decline.

The researchers also stress the importance of precise terminology in a field that has at times blurred conceptual boundaries. Lead author Yanxia Rao notes that terms such as repopulation, transplantation and replacement were historically conflated, potentially obscuring mechanistic interpretation. “Establishing an unambiguous and consistent nomenclature is essential for accurate interpretation of experimental data and clinical outcomes,” she said.

Beyond therapy toward enhancement

While the clinical focus remains on correcting pathogenic mutations, the authors acknowledge that microglia engineering could one day extend beyond disease. Engineered cells capable of delivering neurotrophic or cognitive-supporting factors are discussed as part of a speculative (and excellently-named) “Mr E” – an enhancement variant of the therapy – although they caution that such applications raise ethical and governance questions. As the authors write: “attempts to engineer microglia for enhancement must be preceded by extensive preclinical studies to evaluate the benefit-to-risk ratio,” particularly where circuit-level effects and long-term behavioral consequences are concerned.

A widening horizon

If microglia replacement is to mature into a platform technology, refinements in conditioning, donor sourcing and long-term monitoring will be central. The authors identify priorities including reducing toxicity, improving recruitment cues for donor cells and ensuring that engineered microglia can be deactivated if needed through switch-off systems. The broader trajectory hints at a future in which cell replacement therapies could address not only rare monogenic disorders but also the inflammatory and immune dysregulation that accompany aging.

Shaping what comes next

Microglia replacement invites the longevity field to consider interventions that target the cellular scaffolding of neural health rather than the neurons themselves – a conceptual step that may prove increasingly important as populations age and the burden of cognitive decline rises. Whether the field can retain its pace while ensuring rigor, safety and equitable access remains the critical question, but the work points toward a more pluralistic future for neurodegenerative therapy, one in which immunity, regeneration and aging biology are viewed as deeply intertwined.

[1] https://www.cell.com/cell-stem-cell/fulltext/S1934-5909(25)00407-2

[2] https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1106801