Territorial behavior in academia, or the Gollum effect, affects 44 percent of researchers, a survey found, causing some to shift career trajectories or even behave like Gollum themselves.

Even those who have not seen The Lord of the Rings are likely familiar with Gollum’s iconic line, “My precious,” which embodies his obsession with the One Ring. Gollum’s extreme territorial behavior rang a bell for Jose Valdez, a postdoctoral researcher at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research, as he experienced similar behaviors from fellow researchers as a trainee.

Jose Valdez, an ecologist at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research, coined the term “Gollum effect” to describe territorial behavior in academic research. He recently quantified the frequency and impact of this phenomenon.

Jose Valdez

Valdez and his colleagues noticed that many researchers, especially those in supervisory roles, “felt like they owned or possessed certain topics or ideas, and they’re like, ‘This is my territory,’” Valdez said. “We weren’t even trying to put a name, then ‘my precious’ came out, and we were like, ‘That would be a good name: the Gollum effect.’”

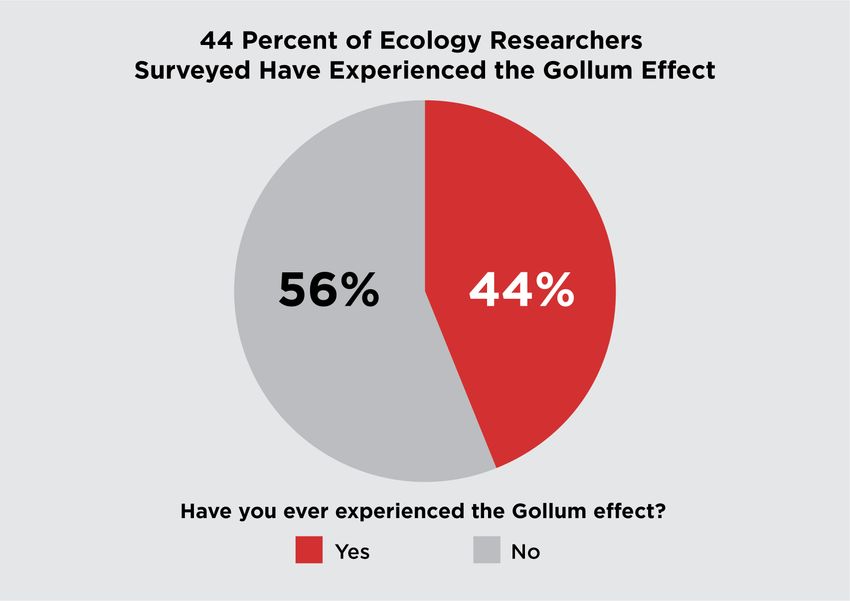

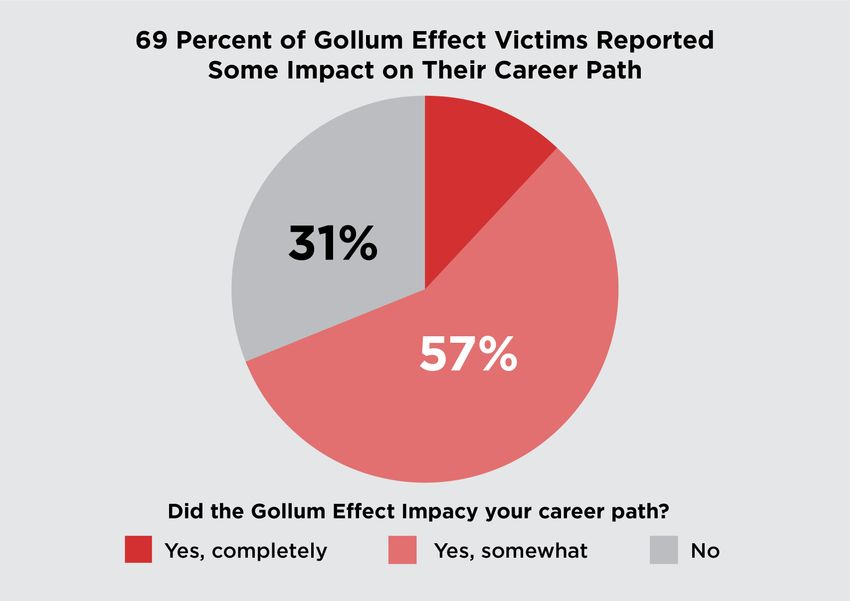

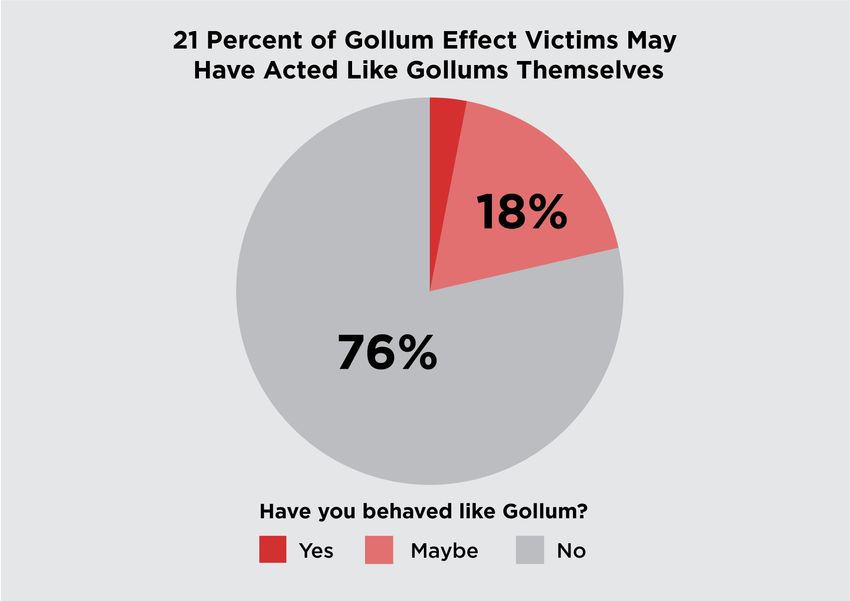

In a recent paper, published in One Earth, Valdez and his colleagues reported that of the researchers they surveyed, about 44 percent had experienced the Gollum effect.1 Among them, nearly 70 percent said that the experience somehow influenced their career trajectory, and about 20 percent admitted to behaving like Gollum themselves. These findings underline the alarming frequency and consequences of the Gollum effect.

247 of 563 survey respondents (44 percent), mostly researchers who study ecology, have experienced the Gollum effect.

Erin Lemieux, The Scientist

While writing an opinion piece on the Gollum effect in 2022, Valdez realized that no one had studied territorial behavior in academic research—claiming of specific ideas and topics, samples, or study sites—and its potential impact on the academic research community.2

Valdez and his colleagues wanted to understand how prevalent this phenomenon was, so they posted a survey on social media platforms commonly used by scientists, including X, ResearchGate, and Reddit, as well as handed out QR codes that linked to the survey at conferences. Between 2022 and 2024, they received responses from 563 researchers, mostly in ecology and the natural sciences, from 64 different countries.

247 of the survey respondents (44 percent) shared that they had experienced the Gollum effect. Among these researchers, nearly 70 percent reported that being a victim of the Gollum effect somehow altered their career path. Notably, 13 percent left academia, and six percent gave up science entirely. “The six percent really stood out to me,” Valdez said. He mostly distributed the survey in academic research circles, so to him, this indicated that the number is probably a lot higher.

69 percent of researchers who have experienced the Gollum effect thought that the experience had an impact on their career trajectory.

Erin Lemieux, The Scientist

Anita Woolley, a psychologist at Carnegie Mellon University who was not involved in Valdez’s work, agreed that both the frequency and impact of the Gollum effect reported in the paper are likely underestimates. “[The Gollum effect] often happens when you don’t even realize it’s happening,” she said. She added that researchers may also subconsciously downplay their negative experiences. “I have a feeling that most people who stay in [academia] may have optimism bias. To really keep going in this field, you have to not focus on [the negatives], right?” Woolley mused.

Both Woolley and Valdez think that the Gollum effect is the product of a systemic problem in academia. In support of this argument, Valdez discovered that about 20 percent of Gollum effect victims admitted that at some point, they too might have acted like Gollum. Academia rewards achievements, ideas, and resources—these are key drivers of the Gollum effect, Woolley said. “We need some other ways to recognize people who are being good community members and create some incentives around being generous and sharing and building knowledge.”

21 percent of Gollum effect victims admitted that at some point, they might have behaved like Gollum themselves.

Erin Lemieux, The Scientist

Woolley noted, however, that “this paper, from a rigor standpoint, isn’t the strongest.” She explained, because the researchers did not report how many people decided not to respond to the survey. For example, whether they had experienced the Gollum effect might have influenced whether they chose to participate, and this could bias the survey results. So, Woolley said, it is difficult to predict how generalizable the researchers’ findings were.

Despite this, she said, “it’s a conversation starter. Illustrating [the Gollum effect] with whatever imperfect data we have might encourage others to continue the work.”

Valdez echoed this sentiment, adding, “We hope that others will follow up on what we did.”