A protein used in red blood cell formation steers dendritic cells to drive regulatory T cell differentiation.

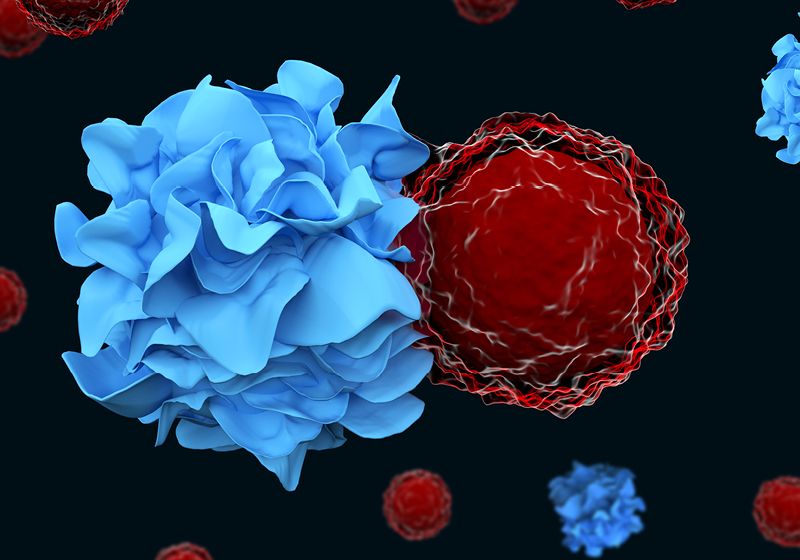

The immune system consists of inflammatory and regulatory T cells (Tregs) that promote or dampen immune activity, respectively. These cells react to specific antigens that specialized cells like dendritic cells present to them. Dendritic cells also provide T cells with directions for what subtype of T cell to become: stimulatory or tolerant.

“What had yet to be discovered is the mechanism responsible for inducing or activating Tregs in those circumstances when they are needed to suppress a dangerous immune response,” said Edgar Engleman, an immunologist at Stanford University, in a press release. Now, Engleman and a team of researchers showed that erythropoietin (EPO), a protein that drives red blood cell production, triggers dendritic cells to become tolerogenic, leading to the development of Tregs.1

“We not only discovered this mechanism, but we also learned how it can be turned on and off,” Engleman continued. The findings, published in Nature, provide new insights into autoimmunity, transplantation, and cancer, where this process may go awry.

To study dendritic cells in a tolerance-promoting environment, the team developed a mouse transplantation model: They irradiated lymphoid organs to deplete T and B cells and then reintroduced bone marrow that did not match the mice’s genetic background. The researchers saw that irradiated mice accepted these mismatched cells as long as they had dendritic cells present. When the team assessed the gene expression of these cells after the bone marrow transplantation, they saw that dendritic cells increased their expression of the EPO receptor (EPOR).

The researchers investigated the importance of this receptor in dendritic cell tolerance by deleting EPOR in dendritic cells. Like removing dendritic cells, the loss of EPOR led to mice rejecting mismatched bone marrow. Using RNA sequencing, the team showed that EPOR-expressing dendritic cells also expressed other immune regulatory genes. Whereas when EPOR was absent, dendritic cells activated genes involved in antigen presentation and cytotoxic T cell responses, indicating a more immune stimulatory phenotype.

Then, to determine if these EPOR-expressing dendritic cells exerted their tolerogenic effects through Tregs, the team depleted these regulatory lymphocytes from mice. They saw that the loss of these cells led to rejection of transplanted bone marrow in mismatched mice. The researchers also showed that culturing naive T cells with EPOR-expressing dendritic cells increased the number of T cells that differentiated into Tregs.

To explore the potential role of this tolerogenic process in cancer, the team implanted mice with either skin or colon tumors. They saw that EPOR-expressing dendritic cells infiltrated these tumors. Tumors with these tolerogenic dendritic cells remained larger than those in mice where the researchers deleted EPOR in dendritic cells. They also showed that these EPOR-expressing dendritic cells decreased antitumor T cell responses, as the deletion of this receptor increased the proportion of cytotoxic T cells and decreased the amount of Tregs in these tumors.

“What was quite a surprise to me is that when you remove or block the EPO receptor on the dendritic cells, you don’t just block the development of tolerance,” Engleman said. “Instead, you have now converted these dendritic cells into super stimulators, or powerful activators of immune response. There is a dual opportunity to not just induce tolerance to treat autoimmune diseases, but also to trigger a strong immune response to cancer cells or to life-threatening infections.”