Engineered MoS₂ nanoflowers help stem cells donate healthier mitochondria, improving energy production and cellular recovery.

Texas A&M researchers have reported a method of coaxing human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) into producing and donating more mitochondria, potentially improving the recovery of damaged cells that rely on imported organelles to restore their energy balance. The work, published in PNAS, sits within a growing effort to understand and eventually manipulate intercellular mitochondrial transfer – a naturally occurring but inefficient process by which cells lend one another energetic support.

The team engineered vacancy-rich molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) nanoflowers that, once taken up by stem cells, stimulate the SIRT1/PGC-1α axis and lead to mitochondrial biogenesis. According to the authors, this results in a two-fold increase in mitochondrial mass in donor hMSCs and a substantial rise in transfer efficiency to recipient cells across several lineages, including smooth muscle cells and cardiomyoblasts. The problem, they note, is that “existing strategies often fall short due to limited efficacy and challenges in delivery” – a difficulty their nanomaterial approach aims to circumvent [1].

Longevity.Technology: The notion of turning mesenchymal stem cells into “mitochondrial biofactories” may sound like something lifted from a futuristic novel, yet this study edges it closer to plausible translational science. Enhancing intercellular mitochondrial transfer has long been an alluring idea – a way of lending struggling cells a fresh lease of energetic life – but the process is lamentably inefficient in nature. If a nanomaterial can coax donor cells into producing and handing over healthier mitochondria at several-fold greater rates, we may be witnessing an early template for organelle-level therapeutics that bypass traditional drug paradigms; after all, when mitochondria falter, tissues age fast and recover slowly. Still, enthusiasm ought to be tempered by the study’s context: everything here is in vitro and exquisitely controlled, and nanomaterials, however elegant, do not always behave so politely in vivo.

What is intriguing, however, is how this work aligns with a broader shift in longevity science toward repairing the cell’s machinery rather than merely managing its decline. Mitochondrial dysfunction underpins a disheartening proportion of age-related disease yet meaningful interventions remain scarce; if boosting natural mitochondrial transfer can restore ATP production, dampen oxidative stress and rescue even doxorubicin-injured cardiac cells, then researchers may have found a promising foothold. The challenge now is to see whether such precision can survive the messiness of complex organisms – biodistribution, safety and regulatory scrutiny are not known for their forgiving natures – but the direction of travel is noteworthy. Organelle-centric therapies may feel esoteric today, yet so too did gene therapy once; longevity biotechnology has a habit of turning yesterday’s curiosities into tomorrow’s platforms, and this nanoflower-enabled mitochondrial rejuvenation may prove no exception.

Researchers involved in the work describe the approach in notably accessible terms. “We have trained healthy cells to share their spare batteries with weaker ones,” said Dr Akhilesh Gaharwar, a professor of biomedical engineering at Texas A&M. “By increasing the number of mitochondria inside donor cells, we can help aging or damaged cells regain their vitality – without any genetic modification or drugs [2].”

PhD student John Soukar echoed this with a nod to practicality: “The several-fold increase in efficiency was more than we could have hoped for. It’s like giving an old electronic a new battery pack. Instead of tossing them out, we are plugging fully-charged batteries from healthy cells into diseased ones [2].”

The long-term implications remain speculative, but the research team is clear-eyed about the potential trajectory. “This is an early but exciting step toward recharging aging tissues using their own biological machinery,” Gaharwar said. “If we can safely boost this natural power-sharing system, it could one day help slow or even reverse some effects of cellular aging [2].”

How the nanoflowers work

The authors report that MoS₂ nanoflowers with atomic defects reduce intracellular reactive oxygen species and activate mitochondrial biogenesis pathways, yielding an increase in mtDNA copy number across hMSCs, smooth muscle cells and neonatal cardiac fibroblasts [1]. Both small (100 nm) and large (250 nm) particles were effective, though the smaller nanoflowers achieved results at lower concentrations – a reflection of their greater surface area and higher catalytic activity. As the paper notes, “these results demonstrate that MoS₂ nanoflowers with atomic vacancies activate the PGC-1α pathway by modulating cellular ROS levels and stimulating the SIRT1 signaling pathway” [1].

Importantly, the nanoparticles did not appear to impede cell viability at concentrations used in the study, and mitochondrial membrane potential was maintained. Flow cytometry confirmed efficient uptake, with clathrin-mediated endocytosis acting as a principal route.

Increased mitochondrial transfer and cellular rescue

Having enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, the researchers demonstrated that donor cells treated with MoS₂ nanoflowers transferred their increased mitochondrial cargo to neighboring cells through tunneling nanotubes. Live-cell imaging captured mitochondria moving into recipient cells within hours, and transfer rates rose two- to four-fold depending on the cell type. Crucially, carrier nanoparticles did not themselves transfer to recipient cells, isolating the effect to mitochondrial exchange.

Recipient cells exhibited higher ATP levels, improved respiratory capacity and reduced oxidative stress following mitochondrial uptake. In models of injury mitochondrial transfer from treated donors restored ATP production and reduced apoptosis markers. In cardiac fibroblasts challenged with doxorubicin, MitoFactory-treated cells showed markedly greater survival, and the authors observed that “enhanced mitochondrial transfer can effectively mitigate mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis” [1].

A platform for regenerative medicine

Beyond the in vitro systems described, the study suggests MoS₂ nanoflowers could serve dual roles: as a preconditioning agent for donor cells in cell therapies and potentially as a platform for targeted nanotherapeutics. The authors acknowledge the need for in vivo assessment of biodistribution, retention and functional integration, noting that MoS₂ materials have already entered preclinical studies in other therapeutic contexts.

Hints of what may follow

The regeneration of energetic competence within damaged cells is an appealing goal for longevity medicine; however, the road from cultured cells to clinical practice is rarely linear. Nanomaterial-enabled mitochondrial rejuvenation may represent a step toward therapies that intervene directly at the level of organelle health – a shift that promises precision but demands careful stewardship. Should the biology hold in more complex systems, the field may find itself with a new class of tools for supporting energy-hungry tissues as they age and repair.

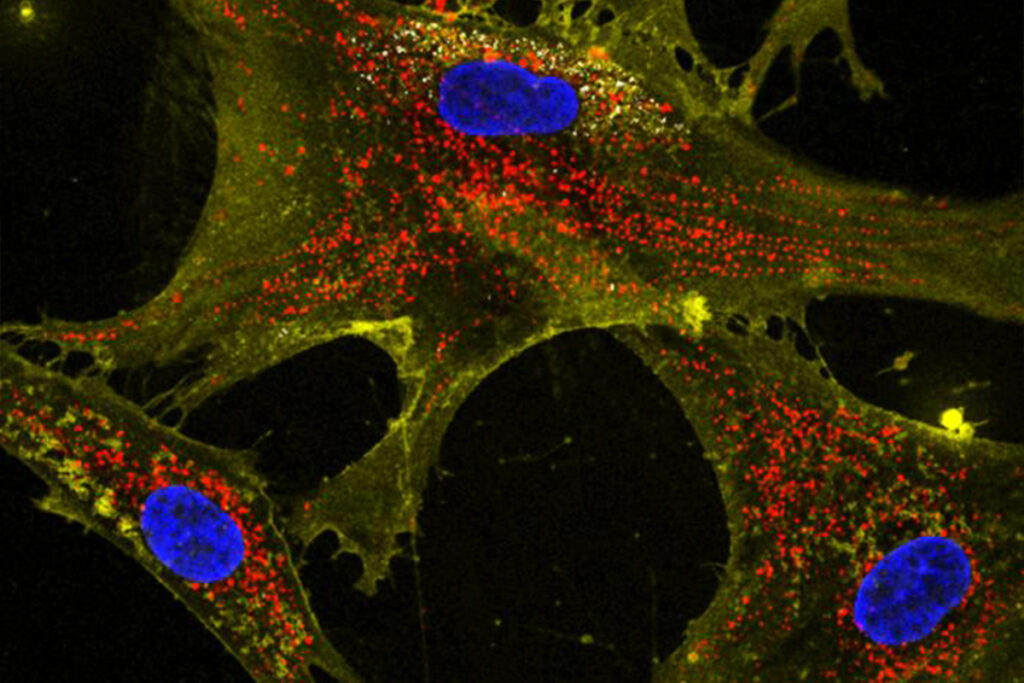

Photo credit: Dr Akhilesh K Gaharwar. Microscopic image showing how nanoflowers (white) help healthy cells (yellow) deliver energy-producing mitochondria (red) to neighboring cells. Nuclei are stained blue.

[1] https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.2505237122

[2] https://stories.tamu.edu/news/2025/12/01/texas-am-scientists-use-nanoflowers-to-recharge-aging-and-damaged-cells/