Natural genetic differences can impact the ability of monoclonal antibody (mAbs) therapies to bind to their target proteins, research suggests.

The findings, in Science Translational Medicine, suggest these variations should therefore be considered in the design of drugs and their clinical use.

They could also impact how the therapies are tested in clinical trials and tailored for individual patients during treatment.

For almost every antibody analyzed, the researchers found protein variants either within or near the antibody-antigen interface. In a significant proportion of cases, these were predicted to disrupt antigen recognition.

“Physicians must be aware of the potential for resistance due to polymorphisms in the targeted epitopes,” maintained Romina Marone, PhD, from University Hospital Basel in Switzerland, and fellow investigators.

“A diagnostic test for known epitope-associated variants could help avoid ineffective treatments in patients carrying those variants and guide treatment decisions, especially when multiple antibodies are available.”

mAbs have become crucial treatments for a wide range of diseases, binding to specific sites on a target proteins in a way.

Because this relies on the interaction of particular amino acids, there is the potential for variations in these target proteins to affect binding activity, and therefore the effectiveness of these therapies.

Marone and co-workers investigated how genetic diversity in epitopes bound by therapeutic mAbs might affect antigen-specific therapies by systematically analyzing the prevalence of naturally occurring single nucleotide variants (SNVs) across human therapeutic antigens.

They then examined how the resulting protein variants could affect the binding of therapeutic antibodies, both those approved and in clinical development.

The team discovered multiple SNVs in the respective epitope regions for every antibody analyzed, a substantial portion of which were predicted to alter antibody binding.

This could occur by directly by disrupting the antibody-antigen interface without affecting the structure or function of the antigen or by indirectly by altering its structure itself.

Further investigations on the impact of 43 SNVs located at 26 epitope residues in four target proteins revealed that, for 19 of these SNVs, there was a reduction or complete loss of antibody binding, consistent with the computational predictions.

The naturally occurring SNVs causes amino substitutions at epitope residues that completely abolish binding of therapeutic antibodies to their target.

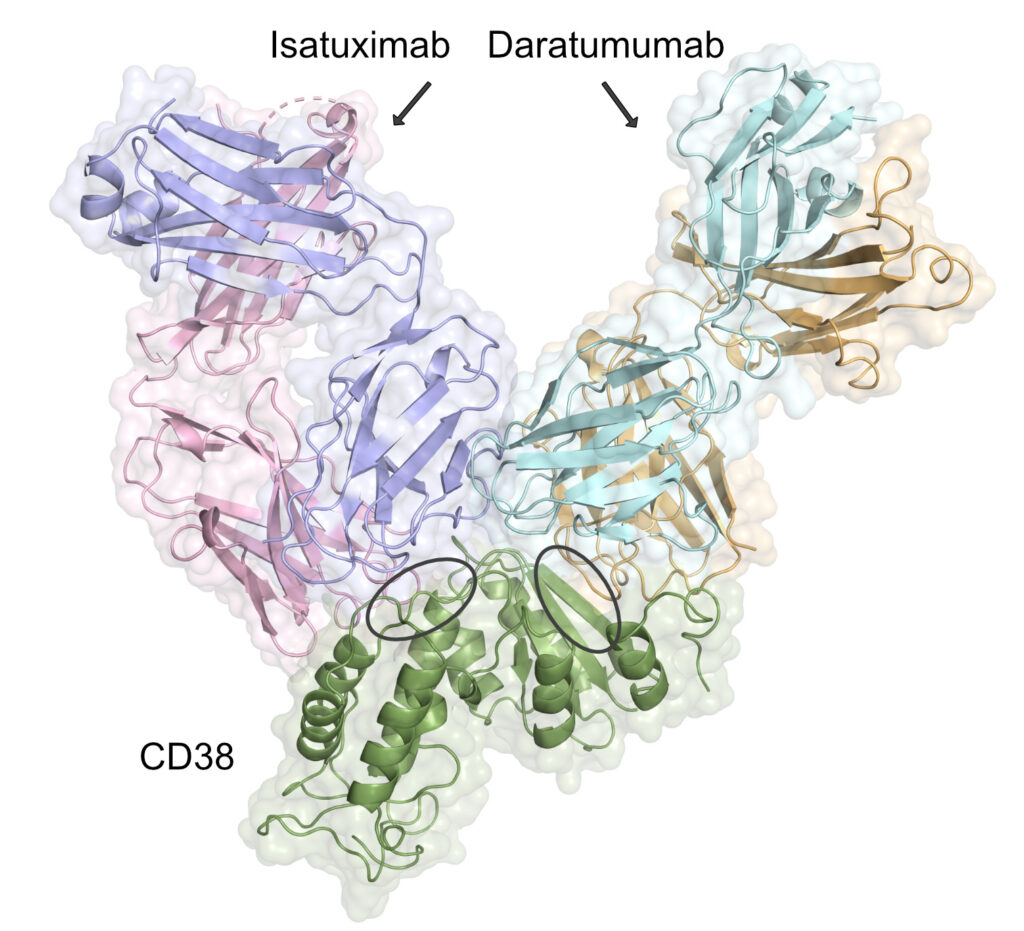

For example, a mutation in CD38 resulted in the loss of binding by daratumumab, which is an mAb approved for multiple myeloma. However, it did not impact the binding of the mAb isatuximab, indicating patient with the variant should this treatment.

In another instance, genetic variation affected antibodies that bound HER-2, impacting on trastuzumab and pertuzumab breast cancer therapies.

“Our findings have important implications for both clinical practice and therapeutic development,” the researchers reported.

“In particular, we argue that integrating genetic testing with accurate predictive models could help identify patients who are less likely to benefit from specific therapies.

“This has the potential to bring clarity for patients and physicians, reduce unnecessary treatments, minimize exposure to side effects, and optimize healthcare resources, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes.

“Moreover, our results may be valuable to the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Accounting for genetic variation could help avoid false-negative outcomes that might otherwise bias clinical efficacy and could inform the development of mAbs targeting alternative, nonoverlapping epitopes, thereby enhancing treatment efficacy and coverage across genetically diverse patient groups.”