A University of Toronto-led study has identified a possible biomarker linked to multiple sclerosis (MS) disease progression. The findings, validated in both mouse and in humans, could help to identify patients most likely to benefit from new drugs.

“We think we have uncovered a potential biomarker that signals a patient is experiencing so-called ‘compartmentalized inflammation’ in the central nervous system, a phenomenon which is strongly liked to MS progression,” explained Jen Gommerman, PhD, a professor and chair of immunology at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “It’s been really hard to know who is progressing and who isn’t.”

Gommerman is co-senior and co-corresponding author of the researchers’ published paper in Nature Immunology, which is titled “Lymphotoxin-dependent elevated meningeal CXCL13:BAFF ratios drive gray matter injury.”

Canada has one of the highest rates of MS in the world with over 4,300 Canadians diagnosed with the condition each year, according to MS Canada. Roughly 10% of people with MS are initially diagnosed with progressive MS, which leads to a gradual worsening of symptoms and increasing disability over time. Patients initially diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, the more common form of the condition, can also go on to develop progressive MS.

“We have immunomodulatory drugs that can modulate the relapsing and remitting phase of the disease,” say co-senior and co-corresponding author Valeria Ramaglia, PhD, a scientist at the University Health Network’s Krembil Brain Institute and an assistant professor of immunology at Temerty Medicine. “But for progressive MS, the landscape is completely different. We have no effective therapies.” Moreover, Ramaglia, notes, until the team’s study, the research field did not have a good model that replicates the pathology of progressive MS.

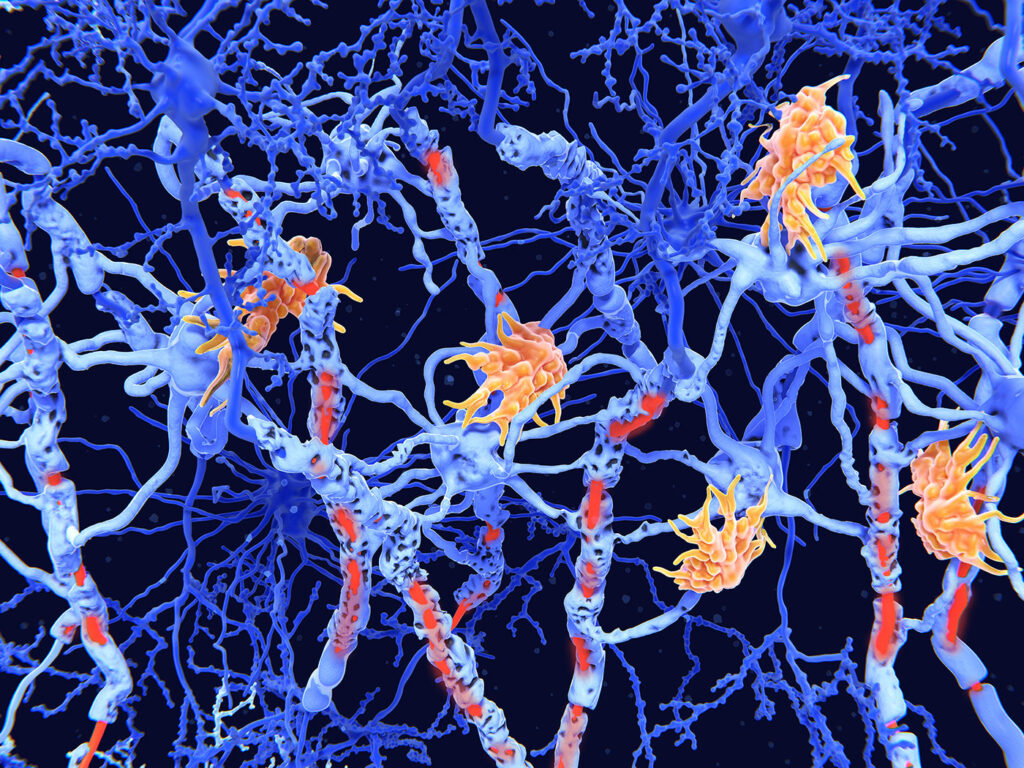

To understand the mechanisms driving progressive MS, Ramaglia, Gommerman and colleagues developed a new mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model that mimics the damage in the brain’s grey matter seen in people with progressive MS. A hallmark of this so-called grey matter injury is compartmentalized inflammation in the leptomeninges, a thin plastic wrap-like membrane that encases the brain and spinal cord. In multiple sclerosis (MS), B cell-rich tertiary lymphoid tissues (TLTs) in the brain leptomeninges associate with cortical gray matter injury,” the authors explained. “Rodent models of MS (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, EAE) that recapitulate brain leptomeningeal TLTs represent our best tool for studying the molecular requirements for TLT formation.”

Using their mouse model, the team observed a roughly 800-fold increase in an immune signal called CXCL13, and significantly lower levels of another immune protein called BAFF. By treating these mice with BTK inhibitor drugs—which are currently being tested in clinical trials to target progressive MS—the researchers mapped out a circuit in the brain that led to grey matter injury and inflammation. They also found that BTK inhibitors restored CXCL13 and BAFF levels to those seen in healthy mice. “Here, using remibrutinib, a selective covalent BTKi in Phase III for MS, our study revealed a leptomeningeal circuitry that drives cortical injury in EAE,” they noted.

“We found that the presence of leptomeningeal B cell-rich aggregates requires both BTK and LTβR signaling, and that these aggregates are associated with low levels of BAFF and high levels of CXCL13 within the leptomeninges.

These results led the researchers to hypothesize that the ratio of CXCL13 to BAFF could be a surrogate marker for leptomeningeal inflammation. To test the validity of their findings in humans, the researchers measured the CXCL13-to-BAFF ratio in postmortem brain tissues from people who had MS and in the cerebrospinal fluid of a living cohort of people with MS. In both cases, a high CXCL13-to-BAFF ratio was associated with greater compartmentalized inflammation in the brain.

“In patients with MS, a high CXCL13:BAFF ratio in the CSF was associated with a greater degree of compartmentalized inflammation,” they stated. “In summary, our study reveals a novel BTK-dependent circuit that establishes B cell-rich TLT in the leptomeninges during EAE, demonstrates that dissolving these structures ameliorates gray matter injury in a BAFF-dependent manner and links high CXCL13:BAFF ratios in the CSF with compartmentalized inflammation in patients with MS.”

To date, BTK inhibitors have generated mixed results in clinical trials with people with MS. Ramaglia says that without an easy way to detect leptomeningeal inflammation, the trials likely enrolled participants who did not have this feature and were unlikely to benefit from the drug. Any positive results from people with compartmentalized inflammation would then be diluted.

“If we can use the ratio as a proxy to tell which patients should be treated with a drug that targets leptomeningeal inflammation, that can revolutionize the way we do clinical trials and how we treat patients,” said Ramaglia. In their paper, the team propose that measuring CXCL13:BAFF ratios in the CSF can help identify patients with compartmentalized inflammation, including leptomeningeal TLT, potentially enabling better patient stratification and treatment monitoring. “By extension, we predict that patients with MS who have a high CXCL13:BAFF ratio in the CSF may particularly benefit from treatment with BTKi.”

As she builds her own research program at the Krembil Brain Institute, Ramaglia is continuing to collaborate with Gommerman to explore how the CXCL13-to-BAFF ratio can be used to advance precision medicine for people with MS. “Future studies should characterize the impact of BTKi on CXCL13:BAFF ratios in patients with MS and on leptomeningeal/CSF B cell phenotype,” the team noted. The investigators are working with the pharmaceutical companies behind the BTK inhibitor trials to look at whether the participants who responded the most to the drugs also had high ratios of CXCL13 to BAFF.

Ramaglia is also planning to look at CXCL13 and BAFF levels in people with early MS to see if it can predict who is likely to develop progressive MS later. She credits her time as a research associate in Gommerman’s lab as playing a key role in helping her become an independent investigator. “Jen’s lab was a huge stepping stone for me. She gave me the space and independence to build my own research.”