Oncology, an industry awash with ever-more sophisticated drugs, has a target problem. Industry reports from 2025 reveal that oncology R&D is highly concentrated, with ~25% of drug-target pairs targeting 38 targets and over 80% of cancer targets facing multiple competing clinical candidates. In other words, oncology R&D primarily concentrates on a tiny slice of the (theoretically) druggable world.

This extremely limited target set is rooted in a lack of specificity—cell types and states for the most part cannot be isolated by a single biomarker. The silver lining is that there is a lot of room for the needle to sway further away from the crude lack of specificity of chemotherapeutics to new drugs that target cancer cell populations finely characterized by multiple targets.

DISCO Pharmaceuticals, spun out of ETH Zürich in 2022, has been shining a light, literally, onto targets in a way no one has before using a platform designed to discover cell surface AND-gated targets: pairs of proteins co-localized on tumor cells but absent from healthy tissue. The preclinical biotechnology company has found itself in an envious position, having identified more promising targets than the preclinical biotechnology company. Big pharma has not only taken notice—they’ve begun to collaborate.

Under a newly announced exclusive license agreement, Amgen will gain global rights to develop and commercialize therapeutic programs against one of several novel cancer targets uncovered by DISCO’s proprietary light-bacell-surface mapping platform. The collaboration pairs Amgen’s drug-development firepower with DISCO’s surfaceome platform. If successful, the strategy could enable a new wave of highly selective antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), T-cell engagers (TCEs), and potentially therapies beyond oncology. DISCO is eligible to receive up to $618 million in total potential value, plus royalties, underscoring the industry’s growing appetite for target innovation at the cell surface.

Co-localized targets for increased specificity

ADCs and T-cell engagers are not new ideas. Versions of both modalities have been in development for more than a decade, and new DISCO CEO Mark Manfredi, PhD, who stepped into the role just weeks before the collaboration was announced, himself worked on them as far back as 15 years ago. “They didn’t really work so well back then,” Manfredi told Inside Precision Medicine. “But over the last five years, there have been some great successes, particularly in the ADC space.”

Those successes are no accident. Advances in linker chemistry have made ADCs more stable in circulation, while new cytotoxic payloads—more potent and better controlled—have improved their therapeutic index. T-cell engagers, too, have benefited from improved engineering that tempers their toxicity.

Yet as these platforms have matured, a bottleneck has become increasingly clear: targets. “Many people are going after the same targets,” Manfredi explained. “Whether it’s ADCs or T-cell engagers, you keep seeing the same antigens come up. What’s been missing are new targets and new ways to get selectivity.”

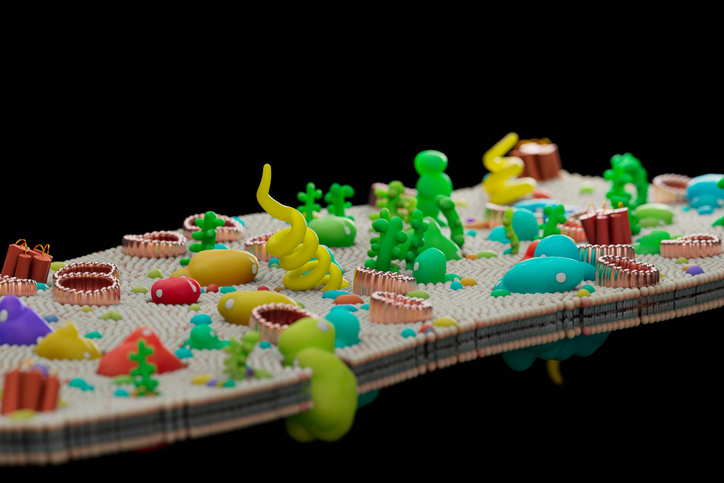

That gap is where DISCO positions itself. At the core of DISCO’s technology is the idea of AND-gating. Instead of targeting a single antigen that may be present on both tumor and healthy cells, DISCO looks for pairs of proteins that are co-expressed and physically close together on cancer cells but not on normal tissue. “The first level of specificity is that both targets are expressed on a tumor cell, and normal cells don’t express both,” Manfredi said. “The antibody is designed so that both have to be present for it to bind effectively.”

In practice, this means that if a cell expresses only target A or only target B, the antibody binds too weakly to matter. Only when both proteins are present—and sufficiently close together—does binding occur with high affinity. Hence the term and-gated: target one and target two must both be there.

Proximity turns out to be critical. Not all proteins that appear on the cell surface are close enough to be engaged simultaneously by a single antibody construct. “If you picked random protein one and protein seven, even if they’re both on the cell surface, they may not be in proximity,” Manfredi notes. “That’s why the co-localization technology is essential.”

Mapping the cancer cell surfaceome

The key to discovering surfaceome protein complexes that can be targeted with AND-gating is a light-controlled technology called LUX-MS, which was created by professors at ETH Zurich who later co-founded DISCO Pharmaceuticals. At the core of LUX-MS, are small-molecule singlet oxygen generators (SOG)—an innovation from the lab of Roger Tsien, who was co-awarded the Nobel Prize in 2008 for green fluorescence protein (GFP). SOG can be coupled to antibodies or ligands and activated by visible light to precisely oxidize targeted cell-surface regions, enabling stable labeling of nearby proteins that can be purified in complexes and deconstructed with robotic mass spectrometry.

DISCO’s platform uses SOG coupled to anchor proteins—known cell-surface oncology targets for which antibodies already exist. Typically, DISCO starts with 10 to 12 such anchors for each cancer type being investigated. These anchors serve as reference points for mapping the surrounding protein environment. By adjusting exposure time, the team can effectively tune the radius of SOG labeling. The resulting protein complexes are analyzed using ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry—one of only a handful of instruments worldwide capable of producing this level of detail. The output is a dense, noisy list of candidate proteins that may be co-localized with each anchor.

Turning that raw data into actionable biology is where DISCO’s computational infrastructure comes into play. According to Manfredi, separating meaningful signal from background noise is one of the platform’s defining challenges. “What DISCO has built is the machine learning technology to pull a map together across all those antibodies and all those cell-surface targets,” he said. “The platform spits out a cell-surface map showing what’s co-localized with what.” The same process is repeated with non-cancerous cell lines, and the resulting data sets are compared to pull out the cancer-specific targets.

But computational predictions are only the beginning. Each candidate pair must be validated through a painstaking series of experiments: confirming that both proteins are on the cell surface, verifying that they are physically co-localized, and demonstrating that their combined expression is enriched in tumors relative to normal tissue. Much of this validation relies on flow cytometry (FACS) and immunohistochemistry (IHC), the latter of which Manfredi describes as a major bottleneck. “That’s why we try to weed out all the junk before we ever get to IHC,” he said. DISCO’s computational team integrates its data with external RNA expression databases to narrow the list to the most promising hits, often just a handful out of thousands.

The process is iterative. New mass-spec experiments feed back into the models, which in turn refine the next round of experiments. Over time, the platform becomes easier to use not only for computational scientists but also for bench researchers.

Too many targets to go alone

The collaboration with Amgen grew out of nearly two years of close interaction between the two teams. While details of the specific target pair involved have not been disclosed, the structure of the deal reflects a clear division of labor. “We’re finalizing the work on our side and sending it over to them,” Manfredi said. “They take it forward from here to develop the therapeutic.”

For DISCO, partnering is not a departure from its core strategy but a complement to it. “Our primary goal is to develop our own programs,” Manfredi emphasized. “We have several internal programs at the same stage as the one we partnered with Amgen on.”

However, the breadth of DISCO’s discovery engine means it inevitably identifies more opportunities than it can advance alone. Strategic partnerships allow the company to extract value from those discoveries while maintaining focus on building its own pipeline. “This year is really about getting to a development candidate centered on our own program,” Manfredi said. “We have several lined up and will choose which one to move forward.”

If DISCO’s approach succeeds, it could reshape how the industry thinks about precision, not by stratifying patients based on biomarkers, but by redefining what constitutes a druggable target in the first place.

While cancer remains DISCO’s primary focus, the company is already extending its platform into non-oncology areas, including immunology and inflammation. “The principle is the same,” Manfredi said. “Are there targets where we need to be more specific?”

In diseases outside oncology, specificity is just as critical, whether it’s limiting immune suppression to a particular tissue or fine-tuning the activity of metabolic drugs like GLP-1 agonists. The challenge, however, is that non-oncology tissues are often scarcer and harder to study, requiring adaptations to the platform. “That’s what we’ve been working on over the last six months,” Manfredi noted.

As ADCs and T-cell engagers continue their resurgence, the question is no longer whether these modalities work, but how selectively they can be deployed. By insisting on two molecular “keys” instead of one, DISCO and Amgen are betting that the next leap forward in cancer therapy will come not from new warheads, but from smarter targeting.

This collaboration underscores that therapeutic technologies aren’t necessarily what’s keeping drug development in oncology from its massive potential, showing us that we don’t need new shovels to uncover hidden treasures—what we need are new maps.