Researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have developed a potentially new treatment strategy aimed at immunologically “cold” tumors by restoring their ability to present antigens to the immune system. The approach centers on an engineered protein system called HLA-Shuttle, designed to manipulate class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA-I) processing so that tumor cells become visible to T cells and to immunotherapies that depend on antigen recognition. The study, published in Science Advances, and focused primarily on neuroblastoma, a childhood cancer which is often difficult to treat.

“Neuroblastoma is a classic example of a cold tumor,” said Nikolaos G. Sgourakis, PhD, a professor in the Center for Computational and Genomic Medicine at CHOP and the department of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of Pennsylvania. “Neuroblastomas have low antigen expression, very few mutations, and very poor T-cell infiltration, leading to less effective immunotherapy strategies. It has been an elephant in the room and required a fresh approach to studying the problem.”

Cold tumors are defined by their failure to provoke an immune response. “This class of cancers…are characterized by low levels of immune cell infiltration with limited signs of inflammation and immune activity,” the researchers wrote. A major reason for this immune evasion is the downregulation of HLA-I proteins, which normally act as molecular barcodes that display peptide fragments on the tumor cell surface. Without sufficient HLA-I expression, T cells cannot recognize tumor cells, limiting both natural immune surveillance and the effectiveness of immunotherapies.

This low antigenicity creates roadblocks to both the development of new immunotherapies development and to their efficacy in treating neuroblastoma, which accounts for 15% of pediatric cancer-related deaths.

Prior research had identified defects in the antigen processing and presentation (APP) pathway as an important mechanism driving immune evasion, with the loss of the HLA-I chaperone tapasin reducing surface HLA-I expression by as much as 90%. The CHOP researchers hypothesized that restoring or expanding tapasin function could enhance antigen presentation in cold tumors.

The concept of HLA-Shuttle emerged from this early direction. It is built around an engineered form of tapasin, called tapasin-TM, that extends chaperoning activity beyond the endoplasmic reticulum and across the secretory pathway.

“HLA-Shuttle restores antigen presentation in immunologically cold neuroblastoma cells, enabling identification of multiple tumor-associated antigens with therapeutic potential,” the researchers wrote.

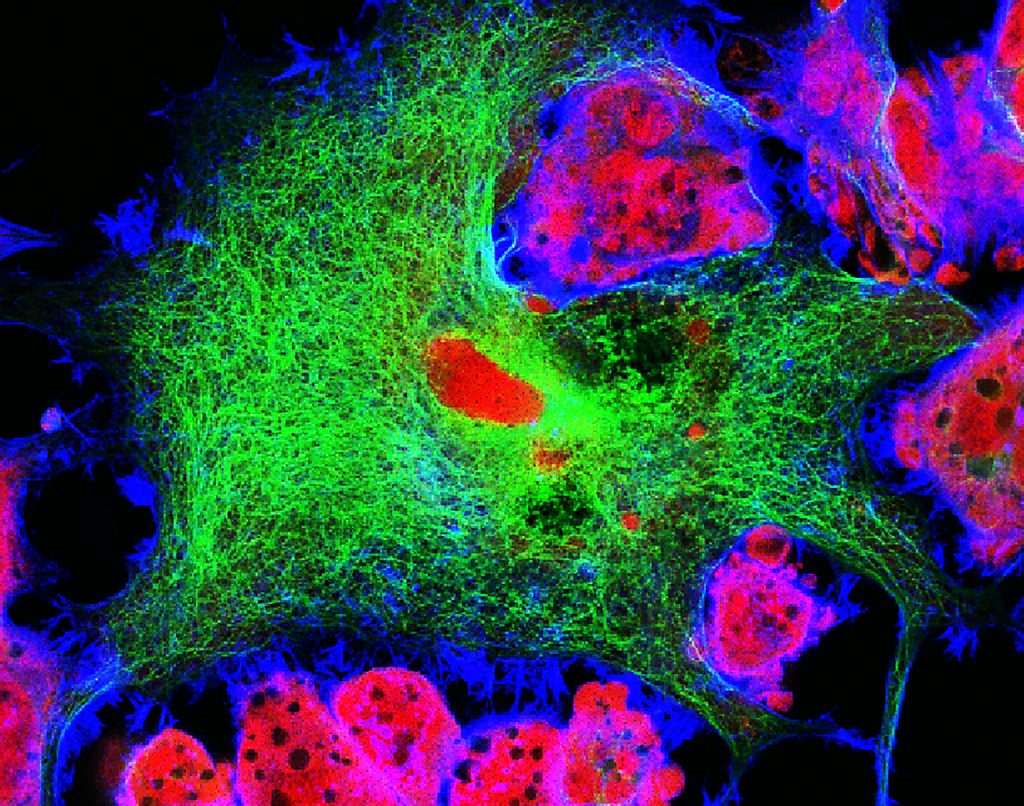

The researchers analyzed the activity of HLA-Shuttle in neuroblastoma cell lines, using cellular trafficking assays, single-particle tracking, and immunopeptidomics. Data from their analysis showed that the approach increased the stability and surface lifetime of HLA-I molecules and reorganized them into microdomains associated with effective T cell activation. They also assessed how the innate immune system responded and found earlier engagement and killing of tumor cells by T cells. “We show that HLA-Shuttle may address this issue by bolstering T cell killing and by enabling identification of potentially relevant [tumor-associated antigens] that were undetectable in the unmodified cells,” the researchers noted.

In addition to its therapeutic implications, HLA-Shuttle also showed it could be used as a drug discovery platform. Using it, the CHOP team identified 180 peptides mapped to 30 genes, including known and understudied tumor-associated antigens. This expanded immunopeptidome included peptides derived from developmentally restricted genes such as PAGE5, HMX1, and ST8SIA2, which have limited expression in normal adult tissues. The researchers reported that “expression of tapasin-TM enabled identification of 844 additional HLA-A2–restricted peptide antigens not detectable in the parental cell line,” while pointing out that the low antigen presentation of cold tumors masks clinically relevant targets.

If developed into an approved drug, the approach could influence clinical care by expanding the range of tumors and antigens accessible to immunotherapy. Neuroblastoma tumors are already known to respond to adoptive cell therapies when appropriate targets are available, and increasing antigen presentation could make cold tumors more susceptible to immunotherapy treatments. Importantly, the researchers also showed that HLA-Shuttle had little effect on cells with normal HLA-I expression, which could potentially point to a therapy with few off-target effects.

The researchers will now expand on this preclinical study to determine whether HLA-Shuttle can be delivered safely in vivo and which tumor types and therapeutic combinations would be of most benefit. This work will include evaluation HLA-Shuttle in other known cold tumors including pancreatic, ovarian, and prostate cancers.