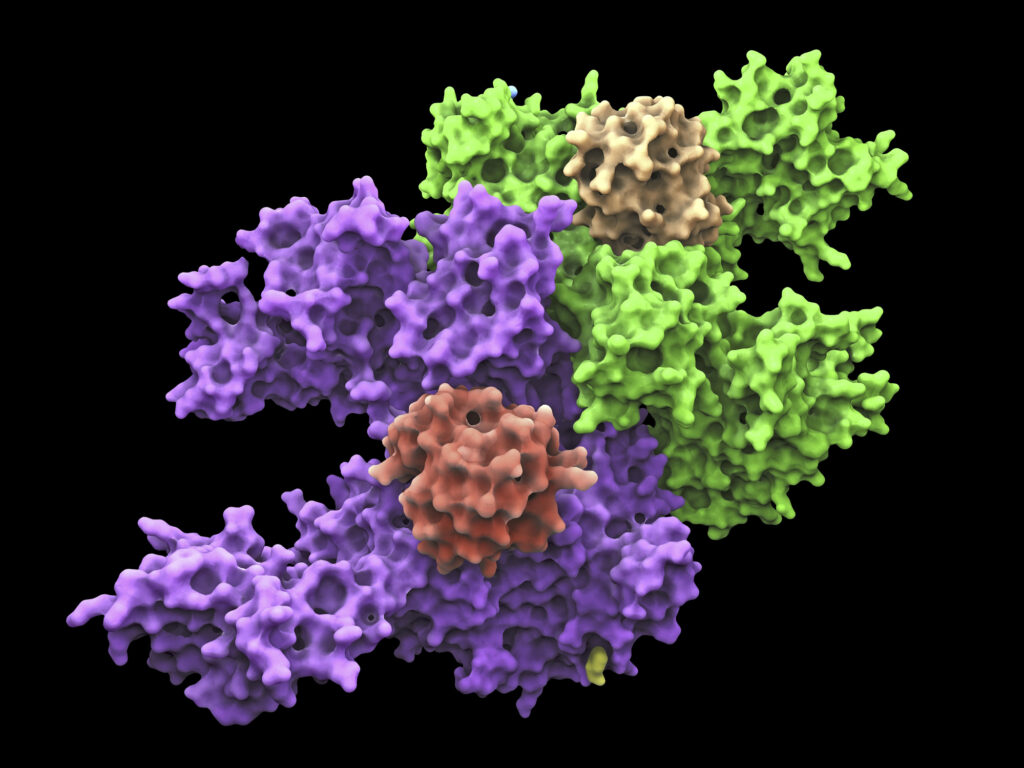

For more than a decade, targeted protein degradation has reshaped how scientists think about drugging disease. Instead of merely blocking an enzyme or interrupting a protein–protein interaction, degraders eliminate the protein altogether, often by forcing it into proximity with an E3 ubiquitin ligase. E3 ubiquitin ligases are the decision-makers of the ubiquitin–proteasome system. They determine which specific proteins in a cell are tagged for destruction, when, and under what conditions. Without E3 ligases, regulated protein degradation would be impossible.

But a new study published in Nature Chemistry describes a different route—one that does not rely on artificially recruiting degradation machinery, but instead accelerates a protein’s own native turnover.

In the paper, researchers report the discovery of a class of small molecules called iDegs that both inhibit and promote the degradation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), a long-standing immuno-oncology target. Instead of functioning as traditional PROTACs or molecular glue degraders, these compounds stabilize a naturally occurring protein conformation that is already prepared for destruction by an endogenous E3 ligase.

“The core message here is really that we can kind of induce or move proteins into states that are just more submissive to being turned around faster,” said Natalie Scholes, PhD, senior postdoctoral researcher at CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine in Austria and co-first author of the study. “Rather than this classical induced proximity event, where we try and recruit something new, like a new E3 ligase, and that prompts degradation.”

A frustrated target in cancer immunology

IDO1 has long been regarded as an attractive cancer target owing to its role in suppressing antitumor immunity. The enzyme catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan into kynurenine, a metabolite associated with immune tolerance. Elevated IDO1 activity and kynurenine levels have been linked to tumor immune evasion, Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoma, and neurodegenerative disease.

Despite strong preclinical data, clinical trials of IDO1 inhibitors have repeatedly failed to provide meaningful benefits for patients. One possible explanation, highlighted in the paper, is that IDO1 has non-enzymatic signaling functions that are not addressed by catalytic inhibition alone—and these may even be worsened when inhibitors increase the protein’s abundance.

“That target has been pursued quite a lot,” Scholes said. “However, inhibitors don’t really seem to do the trick. They don’t really show clinical benefits, at least as far as mouse models went.”

These limitations have fueled interest in degrading IDO1 rather than simply inhibiting it. Previous work has shown that PROTAC-based degraders can reduce IDO1 levels, but these molecules rely on hijacking non-native ligases and tend to be large and complex. Until now, monovalent degraders that act through native pathways have not been described for IDO1.

Pseudo-natural products with a dual effect

The new study identifies iDegs—pseudo-natural products derived from myrtanol—that emerged unexpectedly from a screen originally designed to find enzymatic inhibitors. Instead of acting solely as blockers, the compounds also reduced IDO1 protein levels.

“We were screening for enzymatic function, and they turned out to not just inhibit, but also degrade,” Scholes said. “Then we did the genetic workup and found that we’re basically locking the protein in a state that the endogenous E3 ligase can recognize a bit better.”

Mechanistically, iDegs bind to apo-IDO1—the form of the protein lacking its heme cofactor. This binding induces a conformational shift in the enzyme’s C-terminal helix, stabilizing a degradation-sensitive state.

“All proteins get turned over, and they usually have some matching E3 ligases that control this process,” Scholes explained. “In that case, the small molecules are just tilting the balance toward that state.”

Importantly, heme-bound IDO1 is protected from degradation, while apo-IDO1 is preferentially ubiquitinated. By competing with heme binding, iDegs push IDO1 toward a conformation that favors both loss of enzymatic activity and accelerated destruction.

Beyond classical degraders

The findings point to a broader conceptual shift in targeted protein degradation. Instead of engineering proximity between a protein and an E3 ligase, iDegs amplify an existing degradation circuit by stabilizing a naturally vulnerable protein state.

“The degradation itself is not new,” Scholes said. “It’s more about the nuances of what mechanisms can be used to degrade. Figuring out protein endogenous states and which ones get turned over more—and then forcing the cell to occupy those states a bit more—that’s the new way of thinking.”

This mechanism parallels recent observations in kinase biology, where inhibitor binding can “supercharge” endogenous degradation pathways. The authors argue that such state-based degradation strategies may be more broadly applicable than previously appreciated, extending beyond kinases to other disease-relevant proteins.

Compared with IDO1-directed PROTACs, iDegs are smaller, more drug-like, and rely on a ligase that is naturally expressed wherever IDO1 is present. Their dual mode of action—simultaneous inhibition and degradation—also distinguishes them from other apo-IDO1 inhibitors, which paradoxically increase protein levels.

Implications for oncology and drug discovery

While the study does not claim immediate therapeutic readiness, it reframes how researchers might approach stubborn oncology targets that resist classical inhibition.

“This is a key target in oncology,” Scholes said. “The entire idea was, let’s try and find molecules that abolish the function. Then we stumbled across them being degraders, and then honed in on the mechanism.”

For Scholes, the broader significance lies in what the work reveals about cellular regulation—and how creatively it can be manipulated.

“The cell has so many ways of regulating itself,” she said. “There are so many different ways we can hijack that regulation with small molecules. That’s what’s fascinating, and that’s what opens up new ways of disrupting signaling to help treat cancer patients.”

By revealing a previously unexploited E3 ligase and demonstrating how native degradation pathways can be pharmacologically amplified, the study expands the conceptual toolbox of targeted protein degradation—suggesting that, in some cases, the most effective way to destroy a protein may be to let the cell do what it already knows how to do, just faster.