As a research assistant at the Indian Institute of Science in the mid-2000s, Karthick Balasubramanian monitored the water quality of major South Indian rivers. As part of this work, he would travel to several places in the Western Ghats of India to collect water samples.

“[During] some months, particularly during the winter months, I saw [that] all the stones were covered with brown biofilms,” recalled Balasubramanian. Curious, he brought the stones back to the lab to observe them under the microscope, expecting to find bacteria.

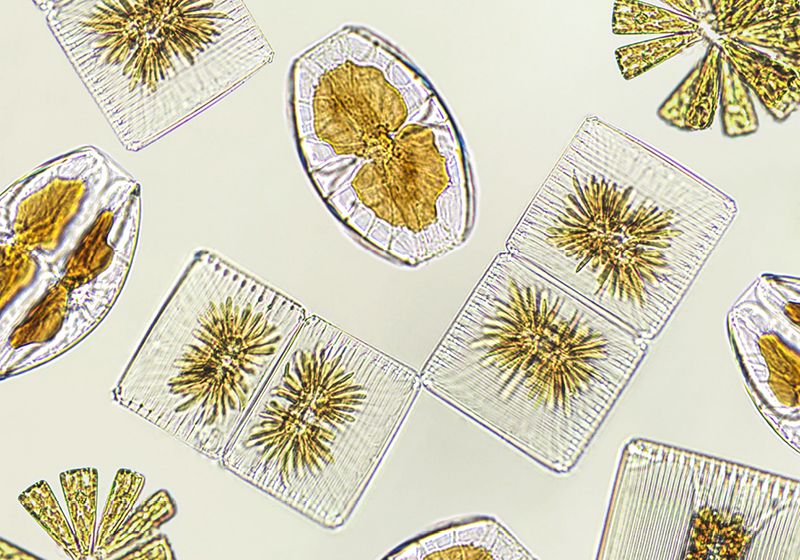

To his surprise, instead of bacteria, he saw beautiful, colorful cells that were symmetric. He would later learn that these were diatoms, a class of microscopic algae with silica cell walls. These tiny cells ended up defining his career. “I never turned back,” said Balasubramanian, who is now a diatom ecologist at Agharkar Research Institute.

When Balasubramanian observed a stone covered with brown biofilm under the microscope, he observed colorful and symmetric diatoms.

Karthick Balasubramanian

Since then, Balasubramanian and his team have studied the diversity and distribution of diatoms all over India, which led them to characterize nearly a hundred species of these microbes. By studying the variety and abundance of diatoms in fossils, the researchers reconstruct past climatic conditions such as temperature and rainfall.1 This helps them understand how these conditions have shifted over the centuries. Over time, Balasubramanian and his team collected more than 5,000 diatom samples from various locations to build South Asia’s largest diatom herbarium.

Diatom Research Pioneer Passes on the Torch

When he started studying diatoms, Balasubramanian came across dozens of research articles authored by a phycologist and diatomist Hemendrakumar Prithivraj Gandhi, who had retired after teaching at JJ Science College in Gujarat. When Balasubramanian tried contacting Gandhi over the phone to learn more about diatoms in 2006, Gandhi’s family asked him to come visit them. He endured a two-day trip from Southern to Western India, which proved to be pivotal to his career.

Upon reaching Gandhi’s home, Balasubramanian found him bedridden and unable to communicate due to Alzheimer’s disease. Despite this, Balasubramanian discussed his work with Gandhi. “I started showing my laptop to him, and then he started telling the names of the diatoms,” recalled Balasubramanian. “His whole family looked at me like [I am] some kind of god because he was not talking to them for many years.”

Balasubramanian spent nearly a week with Gandhi, who had described more than 300 new diatom species over the span of his career. With the hope that Balasubramanian would carry his research forward, Gandhi donated his entire diatom collection to the young researcher.

In 2010, when Balasubramanian discovered a new species of diatom—his first time doing so—he named it Gomphonema gandhii after Gandhi as a tribute to the veteran’s contribution in pioneering the field of diatom research.2 “After that, whatever I did is because of [Gandhi’s] insights,” said Balasubramanian.

Diatoms As Indicators of Climate Change

A few years later, Balasubramanian attended a conference at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, where scientists told him that they discovered diatoms dating back thousands of years in sediment samples. Since diatoms respond to shifts in temperature, rainfall, and light, these microscopic algae are reliable proxy indicators of environmental changes.3,4 This motivated Balasubramanian to investigate fossilized diatoms to study climate change.

Karthick Balasubramanian, a diatom ecologist at Agharkar Research Institute, uses diatoms to study climate change

Karthick Balasubramanian

To this end, he and his team identify the characteristics of diatoms found in ancient samples. “Today, I know what are all the diatoms in high rainfall zones and what are the diatoms in the low rainfall or arid conditions,” said Balasubramanian. Comparing the ancient samples with present-day ones in known climates helps the researchers estimate conditions prevalent in the past.

Using this strategy, Balasubramanian and his colleagues reconstructed the climate variability during the last four millennia in the trans-Himalayan range.5 They examined diatom species and other ancient biochemical proxies such as carbon and nitrogen isotopes and found that westerly winds dominated the area between 4,000 to 2,600 years ago. Soon after, Indian summer monsoons—characterized by higher temperatures and rainfall—set in, probably inducing climate variability and leading to disasters like landslides and debris flows.

Balasubramanian and his colleagues used a similar approach to estimate climate patterns in the Western Ghats of India. By studying diatoms, pollen, and other factors from lake deposits, they found that Southwest Monsoons increased in intensity in the region almost 8,000 years ago.6

Opportunities for Diatom Research

Working in India made Balasubramanian appreciate the biodiversity across the country. “Every 100 kilometers, there is a drastic change in diversity,” he said. He added that scientists are still discovering new species of both bigger animals and microbes in the country, highlighting that much remains to be explored. “That’s kind of [an] opportunity and [a] challenge.”

Zooming into diatoms, he noted that these tiny lives have a lot to offer. In addition to climate monitoring, diatoms come in handy for assessing the health status of water bodies as well as in forensics for analyzing crime scenes. Balasubramanian and his team are also studying the carbon sequestration abilities of diatoms, with potential applications in environmental conservation.

Looking back, Balasubramanian said that one of the most exciting aspects of using diatoms specifically to assess climate dynamics is how many subject specialties intersect in the research. “You need to know about geology. You need to know about environment and physics and magnetism,” he remarked. “It’s real multi-disciplinary, transdisciplinary subject.”

- Phartiyal B, et al. Climate-driven history of last 2600 years: Insights from Bandhavgarh National Park and Tiger Reserve, Central India. Holocene. 2025;35(11):1159-1179.

- Karthick B, et al. The diatom genus Gomphonema Ehrenberg in India: Checklist and description of three new species. Nova Hedwig. 2011;93(1-2):211-236.

- Juffermans E, et al. Diatom responses to rapid light and temperature fluctuations: Adaptive strategies and natural variability. Front Photobiol. 2025; 3:1528646.

- Yogeshwaran M, et al. Soil diatoms and their applications as an indicator of environmental changes. Appl Soil Ecol. 2025;213:106277.

- Phartiyal B, et al. Reconstructing climate variability during the last four millennia from trans-Himalaya (Ladakh-Karakoram, India) using multiple proxies. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2020;562:110142.

- Thacker M, et al. Holocene climate dynamics and ecological responses in Kaas Plateau, Western Ghats, India: Evidence from lacustrine deposits. Quat Sci Adv. 2023;11:100087.