Liver failure claims thousands of lives each year as patients in the United States wait for a donor organ. Now, a research project at the University of California San Diego, funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), aims to change that by developing a fully functional, patient-specific, 3D bioprinted liver. The project, which falls under ARPA-H’s Personalized Regenerative Immunocompetent Nanotechnology Tissue (PRINT) program, provides up to $25,771,771 for a 60-month period.

The multidisciplinary team has the goal of creating “made-to-order” livers grown from a patient’s own cells. The approach could offer a safe, scalable alternative to transplantation that eliminates the need for donor organs and lifelong immunosuppressant drugs.

“When people think about 3D printing, they often imagine making gadgets like cellphone holders or toys, not human organs,” said Shaochen Chen, PhD, professor in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. “But the need for organ transplants is enormous, and 3D bioprinting is uniquely suited to address that challenge, as it allows us to personalize each organ to the patient. Our ultimate goal—the holy grail—is to help solve the organ shortage by printing real, living human organs that can restore health and quality of life.”

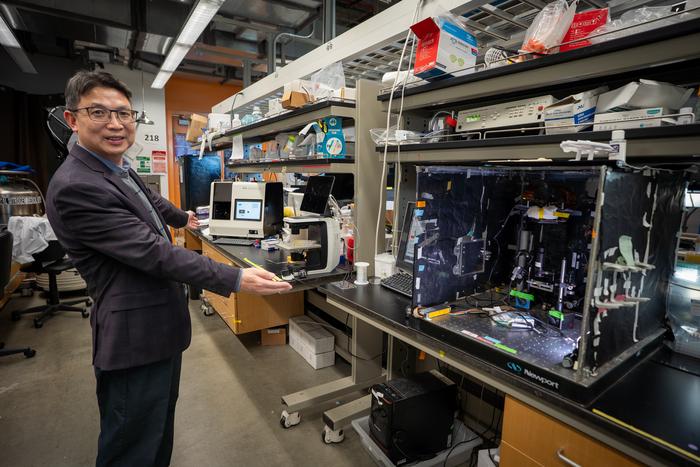

Chen and his lab have developed a technology capable of rapidly fabricating high-resolution biological tissues with complex, multi-cellular structures in just seconds rather than hours. Recently, they integrated artificial intelligence into the design and manufacturing process to help engineer sophisticated vascular networks. This, Chen explained, is one of the key challenges in scaling up from small tissue samples to full-sized, living organs.

The project could provide an on-demand source of functional liver tissue for transplantation, potentially saving the lives of more than 12,000 patients in the United States each year who are currently on the transplant waiting list. The approach could also significantly reduce healthcare costs and improve long-term outcomes for patients with chronic liver disease.

“For decades, the transplant community has dreamed of a future where the fate of thousands of patients each year is no longer determined by the scarcity of donor organs,” said Gabriel Schnickel, MD, professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine, chief of the Division of Transplantation and Hepatobiliary Surgery at UC Dan Diego Health. “This work has the potential to fundamentally change countless lives by moving that vision from aspiration to reality.”

The researchers are collaborating with Allele Biotechnology, an industry partner with expertise in personalized stem cell generation technologies and methods to efficiently produce different types of cells needed to bioprint livers for transplantation. The San Diego company also owns specialized facilities for cell manufacturing that meet regulatory standards. Together, the team plans to advance the process from laboratory-grade to clinical-grade production.

Unlike conventional 3D printing methods, this technology uses digitally controlled light patterns to solidify cell-laden materials layer by layer, allowing researchers to precisely recreate the fine microarchitecture found in living tissues, including intricate networks of blood vessels. Chen and his team launched a startup company, Allegro 3D (now Cellink), to translate the technology beyond the laboratory. As they worked to commercialize the bioprinting platform, they progressively advanced the system from an experimental prototype to an industrial-scale printer capable of producing much larger, more complex structures.