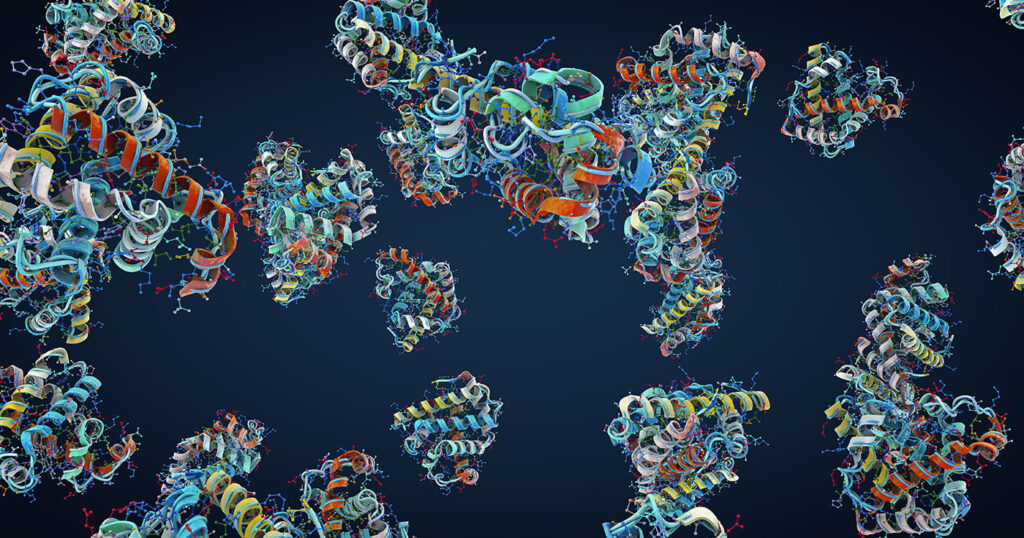

Data from a new Nature study shows the feasibility of engineering a quantum mechanical process inside biological proteins. The study, which was led by an engineering team at the University of Oxford, describes how an engineered protein, dubbed MagLOV “exhibits optically detected magnetic resonance in living bacterial cells at room temperature” with a high enough signal for “single-cell detection.” Full details are published in an open access paper titled “Quantum spin resonance in engineered proteins for multimodal sensing.”

That paper builds on an earlier report of the creation of a new class of biomolecules dubbed magneto-sensitive fluorescent proteins or MFPs, that can interact with magnetic fields and radio waves—MagLOV is one such protein. This ability is due to quantum mechanical interactions within the protein that occur when it is exposed to light sources of a suitable wavelength.

Their work marks the first time that quantum effects have been engineered to develop a practical technology, according to the developers. Historically, “biological candidates for quantum sensors were limited to in vitro systems, had poor sensitivity and were prone to light-induced degradation,” factors that limited their application, they wrote in Nature.

“What blows me away is the power of evolution,” said Gabriel Abrahams, first author on the paper and a PhD student in Oxford’s department of engineering science. “We don’t yet know how to design a really good biological quantum sensor from scratch, but by carefully steering the evolutionary process in bacteria, nature found a way for us.”

The process of directed evolution, which was used to generate the MFPs, involves adding random mutations to a DNA sequence that encodes the protein. The result is thousands of sequence variants with altered properties. From this pool, the scientists selected high performing variants and then repeated the process, introducing new mutations into the altered sequences. Several rounds later, the final proteins generated had a dramatically improved sensitivity to magnetic fields.

“Our study highlights how difficult it is to predict the winding road from fundamental science to technological breakthrough,” according to Harrison Steel, DPhil, an associate professor in the department of engineering science at Oxford. “For example, our understanding of the quantum processes happening inside MFPs was only unlocked thanks to experts who have spent decades studying how birds navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field. Meanwhile, the proteins that provided the starting point for engineering MFPs originated in the common oat!”

The team is already exploring possible applications for the technology. For example, they developed a prototype imaging instrument, as part of this study, that can locate engineered proteins using a mechanism similar to magnetic resonance imaging. It is designed to track specific molecules or gene expression in living organisms in the context of targeted drug delivery or monitoring genetic changes in tumors.

This study is part of a larger initiative dubbed “Quantum sensing in nature and synthetic biology,” that is funded through the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council in the U.K. Its goal is to better understand how animals sense the earth’s magnetic field and to use this information to engineer novel tools with potential biomedical applications.