New kit aims to quantify internal exposure in 7–10 days, offering a noninvasive way to track microplastic particle counts over time.

Microplastics have been detected in air, water and food, and increasingly in human biological samples, raising questions about what chronic exposure might mean for long-term health. Yet for most people, the conversation has remained abstract – a concern in headlines rather than a measurable personal variable.

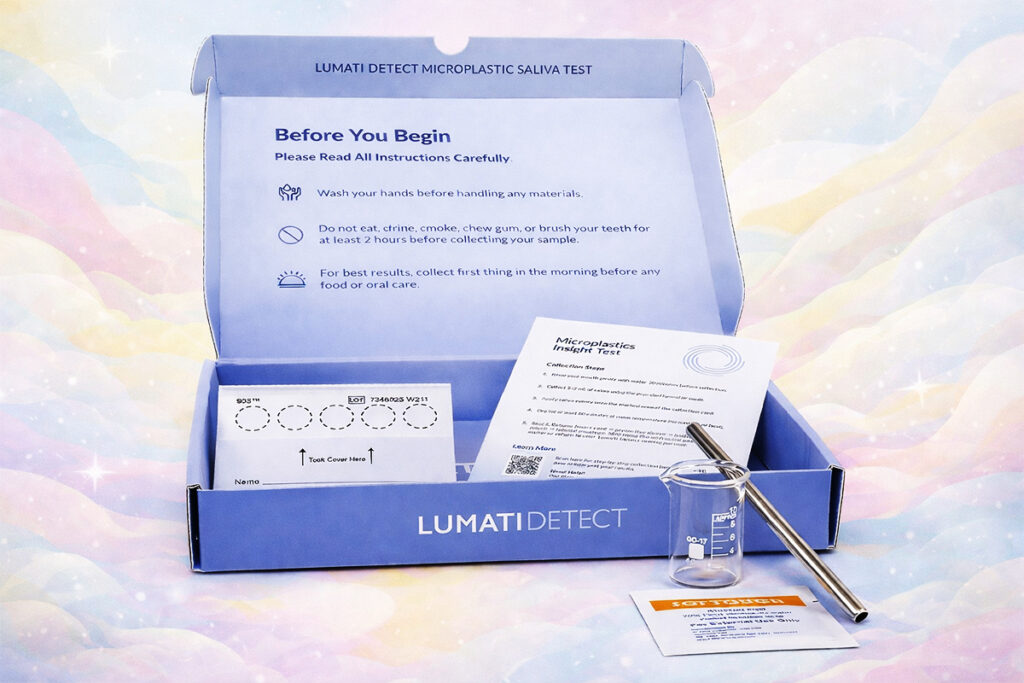

California-based longevity and environmental health company Lumati says it is aiming to change that with Lumati Detect, which it describes as the first at-home saliva test designed to measure microplastic exposure inside the human body. The mail-in kit, which sold out during its launch at A4M Longevity Fest, allows users to collect a saliva sample at home, send it to a certified US laboratory for analysis. Customers then receive a secure digital report within seven to 10 days, with results including total particle count, concentration and size ranges.

Longevity.Technology: Microplastics have become big news, making the leap from obscure toxicology to mainstream dinner-party dread with remarkable speed. This makes Lumati’s at-home saliva test feel like a product arriving bang on cue; when the public can sense a problem but can’t quantify it, measurement becomes its own form of reassurance. The deeper story, though, is not just consumer curiosity – it is the quiet elevation of the exposome into the longevity conversation, an acknowledgment that healthspan is shaped as much by what surrounds us as what we swallow, supplement or schedule into our routines. Still, the line between “making the invisible visible” and turning uncertainty into a new wellness anxiety is thin; without validated thresholds or a clean dose-to-disease curve, microplastics testing should be read as a near-term exposure signal rather than a personal verdict on future pathology. If Lumati can hold that nuance – rigorous contamination control, careful interpretation, trendlines over single results – it may help shift microplastics from helpless abstraction to practical prevention, which is where longevity science tends to become genuinely useful.

Priced at $150, the test is available nationwide, with Lumati recommending periodic retesting for those who want to monitor how exposure may shift with changes in environment or daily habits; users also receive access to the Lumati app, which provides step-by-step collection guidance, a progress tracker and interpretation support alongside the digital report. In the company’s view, saliva offers a practical, noninvasive “exposure window” for biomonitoring, although Lumati emphasizes that Detect is not a diagnostic tool and is not intended to predict disease risk – a distinction that will matter as consumer-facing exposure testing moves from curiosity to routine. With that in mind, we spoke to Lumati CEO David Perez about why the company chose saliva, what the results can realistically tell users and how exposure tracking may fit into the broader longevity toolkit.

Why saliva, and what the test is really measuring

For Perez, the drive to quantify these hidden environmental variables is deeply personal. His path into longevity science was catalyzed by a decade spent researching global medical treatments for his son’s unique health conditions – a journey that transformed from a family necessity into a mission to positively impact one billion lives. This background in high-stakes health research grounds Lumati’s move into microplastics in a sense of urgent, patient-centered utility rather than just market trend-following.

Perez frames saliva as a pragmatic choice rather than a gimmick, arguing that it sits at the point where two of the most common microplastic exposure routes converge: ingestion and inhalation. “Saliva is compelling as a noninvasive testing route because it sits at the crossroads of the two biggest, everyday ways we are exposed to microplastics,” he says, noting that particles can arrive directly through food and drink, or deposit from air and then clear into the oral cavity.

He also positions saliva within a longer history of biomonitoring, describing it as an established proxy in toxicology where blood-adjacent insight is needed without an invasive draw. Saliva, he says, is “generated by the body from water in the blood,” and is used widely as a noninvasive stand-in for what may be circulating systemically.

Still, Perez is careful to temper expectations about what a saliva-based result can and cannot claim. Lumati Detect, he says, should be understood as capturing a “recent-to-near-term exposure signal” – in effect, “what your body is encountering and clearing into the oral cavity over days or weeks” – rather than a definitive measure of lifetime body burden. He stresses that microplastics science has not yet produced validated human thresholds, nor a straightforward “dose → disease” relationship, meaning results are best interpreted as exposure information rather than predictive health data.

To reduce the risk of over-reading the report, Lumati encourages users to focus on trendlines rather than single snapshots, using baseline testing followed by retesting after targeted changes. Perez also points to size distribution as an additional layer of context, suggesting that shifts toward smaller or larger particles may offer clues about potential pathways and behaviors, even if they cannot be treated as diagnostic signals. Consistency matters, too; he advises users to follow the same collection protocol each time in order to reduce noise from normal day-to-day variability.

On the analytical side, Perez emphasizes the central technical challenge in microplastics measurement: contamination. Lumati’s laboratory workflow, he says, was designed to limit plastic introduction during handling, with the goal of ensuring that detected particles are “far more likely to reflect the sample rather than the lab environment.”

“No measurement is ever ‘perfect,’” he adds, “but contamination control is essential in this category.”

To solve this, Lumati’s CLIA/COLA-certified lab partner bypassed traditional Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) methods. While LC-MS is a standard in blood analysis, the equipment and storage materials are frequently coated in plastics, which can introduce the very particles the lab is trying to measure. Instead, they developed a proprietary Fluorescent Microscopy (FM) methodology that uses a strictly controlled workflow of glass, metal and paper to ensure that the results reflect the user’s biology, not the lab environment.

What retesting can reveal, and what might actually change results

While Lumati recommends periodic retesting, Perez describes it less as routine checking and more as a way to make a variable exposure problem interpretable. Microplastic exposure, he argues, fluctuates significantly from day to day, which makes one-off numbers less useful than patterns observed under consistent conditions. In early retesters, he says the company has seen three broad trajectories: stable results, meaningful decreases after reducing one or two major exposure sources and noisy results when sampling conditions change or interventions are inconsistent.

Those disruptions, he notes, can include travel, home renovation projects or spikes in household dust exposure – factors that may not feel relevant to “microplastics” at first glance but can influence what a saliva sample is capturing.

Perez says reductions can be substantial when individuals make sustained changes, claiming Lumati has observed “up to 90% reductions over the course of a year simply by exposure reduction.” The most effective interventions, he suggests, are rarely exotic. The priorities are practical: avoid heating food in plastic, switch plastic storage to glass or steel and reduce contact with plastic utensils and cookware where possible. Water choices can matter, too, particularly where bottled water is a major source, and Perez highlights indoor air and dust as another overlooked driver, recommending improved ventilation, HEPA filtration and efforts to lower synthetic dust load.

Some exposure sources are even more mundane than most people expect. Perez points to chewing gum as one example, citing emerging research suggesting it may shed microplastics directly into saliva – exactly the kind of behavior-linked signal a saliva test could reveal.

In terms of timeframe, he suggests users looking for change should think in months rather than days; with consistent intervention, he says it is reasonable to look for improvement within roughly 30 to 90 days, with longer trendlines offering clearer insight. The goal, he adds, is not perfection but practicality: identifying which adjustments measurably reduce an individual’s exposure signal.

From personal awareness to population-level insight

Perez positions Lumati Detect first as a personal prevention tool – an attempt to “make the invisible visible,” establish a baseline and then test whether exposure-reduction steps appear to be working. However, he also argues that consumer testing could contribute to a wider surveillance layer over time, particularly because a persistent barrier in microplastics research is the limited availability of scalable, real-world exposure data in humans.

Lumati, he says, is working with toxicologists in an effort to better understand impact, with personal optimization acting as an early proving ground for protocols that could later feed into more formal research and standards. Public health guidance remains underdeveloped, he acknowledges, with regulatory bodies still lacking widely adopted guideline values for microplastics exposure, but he sees an opportunity for aggregated data to help map variation by geography, occupation and lifestyle.

If that evidence base grows responsibly, Perez suggests, it could begin to inform product standards, workplace practices and policy conversations – moving microplastics from a diffuse environmental concern toward something that can be measured, compared and ultimately reduced.

When prevention becomes measurable

What makes tools like this worth watching is not the novelty of testing, but the shift in mindset they represent – a move from vague environmental unease to something closer to actionable accountability. If the longevity field is serious about prevention, it will have to get comfortable with the idea that progress is not always a new molecule or a better mouse model; sometimes it is a clearer picture of what is already in the room with us, quietly shaping physiology in the background.