T cells edited to attack tumor-associated macrophages and produce inflammatory cytokines decrease tumor burden in mice, employing a “Trojan horse” strategy of disarming the tumor’s protectors and opening them up to killing.[SD1]

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy improves the detection and elimination of cancerous cells by genetically editing a patient’s immune cells to target tumor-associated antigens. This type of immunotherapy works against multiple types of blood cancers. However, it has been less effective against solid tumors.

One of the challenges with targeting tumors in a solid tissue is that the tumor microenvironment (TEM) shields the cancerous cells against immune attack.1 These defenses include immune cells, like macrophages, that the tumor reprograms to dampen immune responses around it.2 Researchers have tried to target these tumor-associated macrophages with CAR T cells, but this approach has not led to significant tumor killing.3,4

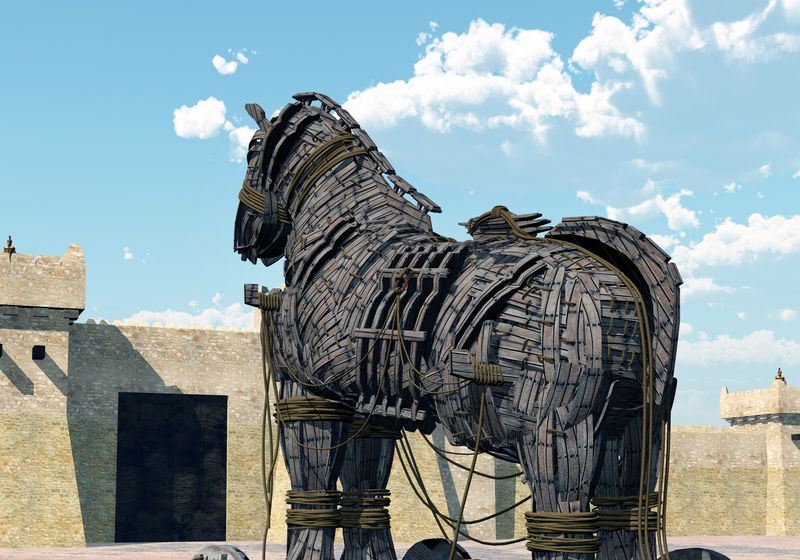

In a study published in Cancer Cell, a team of researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Washington University in St. Louis used a Trojan horse strategy to target tumor-associated macrophages and reprogram the TME to promote tumor killing.5 With this approach, they successfully decreased tumor burdens of two different cancers in mice, paving the way for new CAR T cell therapies for solid tumors in humans.

The researchers first engineered their CAR T cells to target a tumor-associated antigen that these macrophages express more of compared to macrophages outside of the TME. Then, after transplanting mice with either ovarian or pancreatic tumors and depleting their lymphocytes, the researchers treated the animals with these macrophage-targeting CAR T cells. They saw that, while the immunotherapy accumulated at the site of the tumor and killed the tumor-associated macrophages, it did not decrease the tumor burden in the mice.

To improve this approach, the researchers explored encoding their CAR T cell with proinflammatory genes that would activate local immune cells while killing tumor-associated macrophages. Initially, they saw either no difference in the effects on the tumor or systemic toxicity when they used this Trojan horse approach in ovarian tumor-bearing mice that had had their lymphocytes depleted.

Aiming to alleviate the systemic toxicity, the researchers selected CAR T cells loaded with genes to produce interleukin (IL)-12 to trial in animals without depleting their lymphocytes and at a lower therapeutic dose. This reduced the toxicity while still providing tumor-killing benefits in both ovarian and pancreatic cancer models.

The team used spatial transcriptomics to evaluate how the IL-12-producing, tumor-associated macrophage targeting CAR T cell therapy was modulating the TME. In addition to a reduced number of tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in tissue from treated animals, the Trojan horse CAR T cell strategy increased the number of myeloid cells and T cells—specifically cytotoxic CD8+ T cells—and proinflammatory macrophages in the TME.

Finally, to demonstrate the range of this approach, the team created a second Trojan horse-style CAR T cell that targeted a different tumor-associated macrophage antigen seen in lung cancers. Similar to their ovarian and pancreatic tumor CAR T therapy, this second CAR T effectively targeted and killed tumor-associated macrophages in a mouse model of lung cancer. They showed that this CAR T cell therapy also induced similar changes to immune cell populations in the TME as in their previous CAR T cell model.

“This establishes a new way to treat cancer,” said Brian Brown, an immunologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a study coauthor, in a press release. “By targeting tumor macrophages, we’ve shown that it can be possible to eliminate cancers that are refractory to other immunotherapies.”