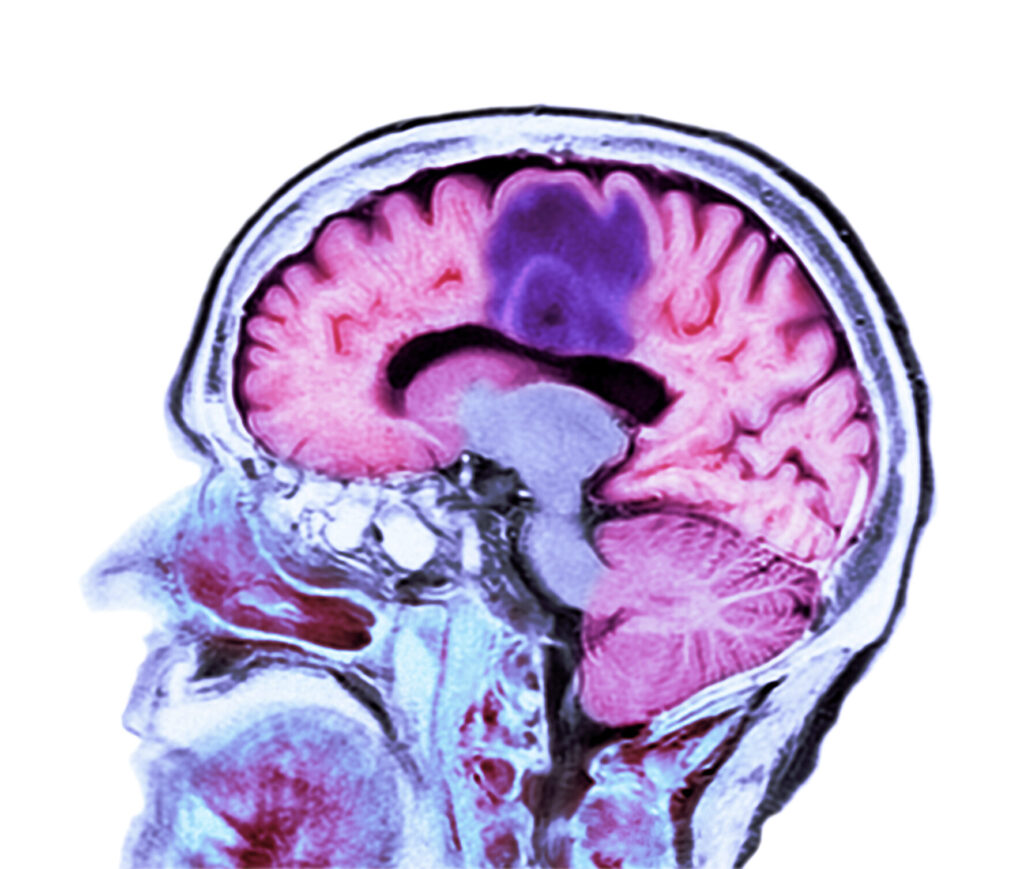

Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most aggressive and lethal brain cancers, in large part because of its uncanny ability to infiltrate the brain far beyond the visible tumor mass. Even after maximal surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, tumor cells often migrate along white matter tracts, seeding recurrence throughout the brain. A new study in Neuron now adds a surprising accomplice to this process: oligodendrocytes, the myelin-producing glial cells traditionally known for insulating neurons and supporting neural repair.

In the paper, co-senior author Sheila Singh, MD, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and colleagues show that glioblastoma cells actively recruit and reprogram nearby oligodendrocytes, converting them into “reactive” cells that secrete signals promoting tumor migration. The work expands the rapidly growing field of cancer neuroscience and points to a clinically actionable pathway that could potentially be blocked using an already FDA-approved drug.

“There’s been a lot of focus recently on how normal brain cells communicate with tumor cells,” Singh said. “That idea alone shocked people—why would a normal brain cell participate in helping a brain tumor grow? But cancer is very good at hijacking the nurturing capacity of normal cells.”

An overlooked player in cancer neuroscience

Previous studies have shown that glioblastoma cells form synapse-like connections with neurons and that astrocytes can support metastatic cancer cells in the brain. Oligodendrocytes, however, had largely remained on the sidelines. That omission is notable given their central role in producing myelin, maintaining axonal conductivity, and responding to injury in conditions such as multiple sclerosis or traumatic brain injury.

“We’ve implicated oligodendrocytes in many neurological disease processes for a long time,” Singh said. “But not yet in brain cancer. In glioblastoma, their role had only really been hinted at.”

Using a combination of molecular profiling and functional studies, the team uncovered a stepwise signaling cascade that explains how GBM cells co-opt these myelin-forming cells.

Four steps to invasion

Singh points to the paper’s graphical abstract as the clearest summary of the mechanism. In the first step, glioblastoma cells secrete an inflammatory chemokine signal that acts like a false wound-healing cue. “It’s essentially saying to the oligodendrocytes, ‘Come here, help me,’” she explained.

Oligodendrocytes at the tumor border express the corresponding receptor and migrate toward the tumor mass. Once in close proximity, glioblastoma cells deliver a second set of signals that reprogram the oligodendrocytes into a reactive state—cells primed for repair but now acting in service of the tumor.

“These reactive oligodendrocytes start secreting cytokines back to the tumor cells,” Singh said. “And those signals help the glioblastoma cells migrate.”

This migration is central to the disease’s lethality. If GBM were a discrete mass, surgeons could potentially remove it. Instead, tumor cells extend finger-like projections that latch onto white matter tracts, allowing them to invade distant brain regions and even cross into the opposite hemisphere.

“It’s the migration that kills,” Singh said. “Once the entire brain is infiltrated, surgery can’t cure you, and radiation has limited effect because these cells already know how to escape it.”

A late-stage signature—and a target

Notably, the oligodendrocyte-driven signaling program was most prominent in treatment-refractory, recurrent glioblastoma rather than at initial diagnosis. That suggests the pathway is tied to disease progression and late-stage invasion.

“That gives us insight into staging,” Singh said. “The oligodendrocytes seem to be helping glioblastoma get to the later, more aggressive stages of disease.”

The final step in the cascade involves activation of a chemokine receptor pathway that can be pharmacologically blocked. The team identified maraviroc—an FDA-approved CCR5 antagonist originally developed for HIV—as a potent inhibitor of this terminal signal.

“The wonderful thing about maraviroc is that it can be repurposed,” Singh said. “We already know it’s safe in humans and not very toxic.”

In mouse models, treatment with maraviroc significantly impaired glioblastoma cell migration. Importantly, because the drug targets a cancer-specific signaling axis rather than the core biological functions of oligodendrocytes, it did not interfere with their normal roles in myelin maintenance or repair.

“You’re only dealing with the abnormal cancer signaling,” Singh said. “You’re not blocking their ability to repair other damage in the brain.”

From mechanism to patients

With a clear mechanism and an approved drug in hand, Singh’s group is now focused on translating the findings to patients. A key step is collaboration with SAGE Medic, a California-based company that operates a CLIA-certified functional precision oncology platform. Using tumor tissue obtained during surgery, the company generates patient-specific organoids and screens them against panels of drugs to identify individualized vulnerabilities.

Singh helped the company develop a glioblastoma drug panel that includes maraviroc. Because the platform is CLIA-certified and the drug is already approved, there may be opportunities for rapid, real-world testing in patients with treatment-refractory disease. If a patient’s own tumor organoids show strong sensitivity to maraviroc, an oncologist could consider off-label use under informed consent, potentially as a phase zero study or through compassionate access.

“Once you have first-in-human data showing activity in glioblastoma, that’s when you can really attract funding for a clinical trial,” Singh said.

Reframing the tumor microenvironment

Beyond its therapeutic implications, the study underscores a broader shift in how researchers think about glioblastoma—not just as a mass of malignant cells, but as a complex ecosystem that includes neurons, glia, and immune elements.

“If you could block these signals and prevent migration,” Singh said, “maybe you could keep the disease more like a lump. And a lump is something a surgeon can actually deal with.”

For a cancer that has seen little improvement in outcomes for decades, that reframing—and the prospect of repurposing an existing drug—offers a rare note of optimism.