It is known that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) increases the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). But the underlying mechanism—and the genetic drivers—between this link remain yet to be determined. Genetic variants in TNFSF15, encoding tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like cytokine 1A (TL1A), are associated with both severe IBD and advanced CRC.

Now, a new study points to immune reactions in the gut—driven by a key signaling protein and a surge of white blood cells from the bone marrow—to help explain why people with inflammatory bowel disease have a higher risk of colorectal cancer.

This work is published in Immunity in the paper, “Innate lymphoid cells activated by the cytokine TL1A link colitis to emergency granulopoiesis and the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils.”

IBD, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is characterized by chronic gut inflammation. Between 2.4 and 3.1 million Americans have the condition, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IBD raises the risk of other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions and greatly increases the risk of colorectal cancer, which tends to occur at younger ages and with worse outcomes in patients with the condition.

The research sought to explore how TL1A signaling promotes colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Experimental drugs that block TL1A activity have shown great promise against IBD in clinical trials, but how the signaling protein promotes the disease and associated tumors has been unclear. The work suggests that TL1A has much of its impact through the tissue-resident type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) in the gut.

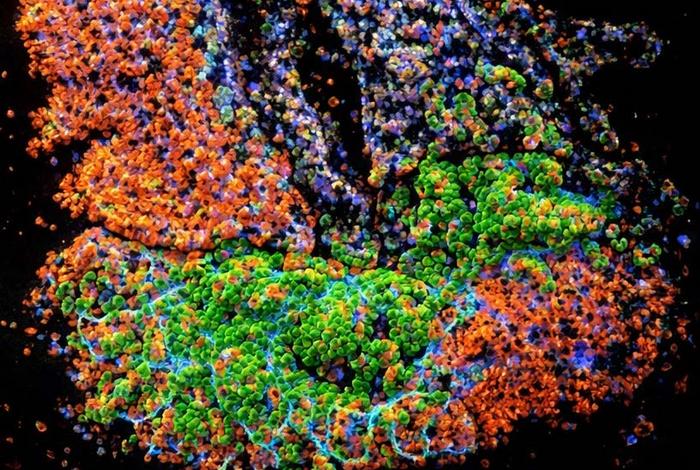

Not only did deletion of the TL1A receptor in the ILC3 cells reduce colitis-associated tumorigenesis, but TL1A signaling promoted neutrophil recruitment to the colon promote tumor formation.

When activated by TL1A, these cells secrete the blood cell growth factor granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This in turn triggers a process called “emergency granulopoiesis”—a burst of new neutrophil production in bone marrow—followed by the influx of the neutrophils to the gut. In mouse models of gut cancer, adding such neutrophils was enough to promote tumor development.

Neutrophils can promote colorectal tumors by secreting highly reactive molecules that can damage DNA in gut-lining cells. However, the team found that the gut ILC3s also induce a distinctive pattern of gene activity in the neutrophils including increased expressions of genes known to promote tumor initiation and growth. The researchers observed a similar gene activity pattern in samples of colitis-affected gut tissue from patients with IBD, and this tumor-promoting signature was less evident in patients who took an experimental TL1A-blocking treatment.

They write, “TL1A-stimulated ILC3s activated neutrophils, inducing a tumor-associated neutrophil (TAN)-like gene signature, and transfer of these neutrophils was sufficient to promote tumor growth. A similar TAN-like gene signature was enriched in human colitis-associated dysplasia but reduced following TL1A blockade in ulcerative colitis patients.”

“These findings are important given the intense interest in the medical community to understand TL1A’s role in IBD and its potential role in associated colorectal cancers—for which we have had few strategies to mitigate the cancer risk,” said Randy Longman, MD, PhD, director of the Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

The results suggest that not only TL1A but also ILC3s, GM-CSF, and ILC3-summoned neutrophils could be targets in future strategies to treat IBD and prevent associated colorectal tumors.

“I think it will be exciting for clinicians in the IBD field to know that there is a systemic process at work here, involving both the gut and the bone marrow, with the potential to drive precision medicine in IBD,” said Sílvia Pires, PhD, an instructor in medicine and member of the Longman Laboratory.