Scientists at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have developed an experimental immunotherapy that takes an unconventional approach to metastatic cancer. Rather than targeting cancer cells directly, the new strategy—which they suggest is akin to that of the Trojan horse—targets the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) that protect the tumor and keep the tumor microenvironment (TME) immunosuppressed.

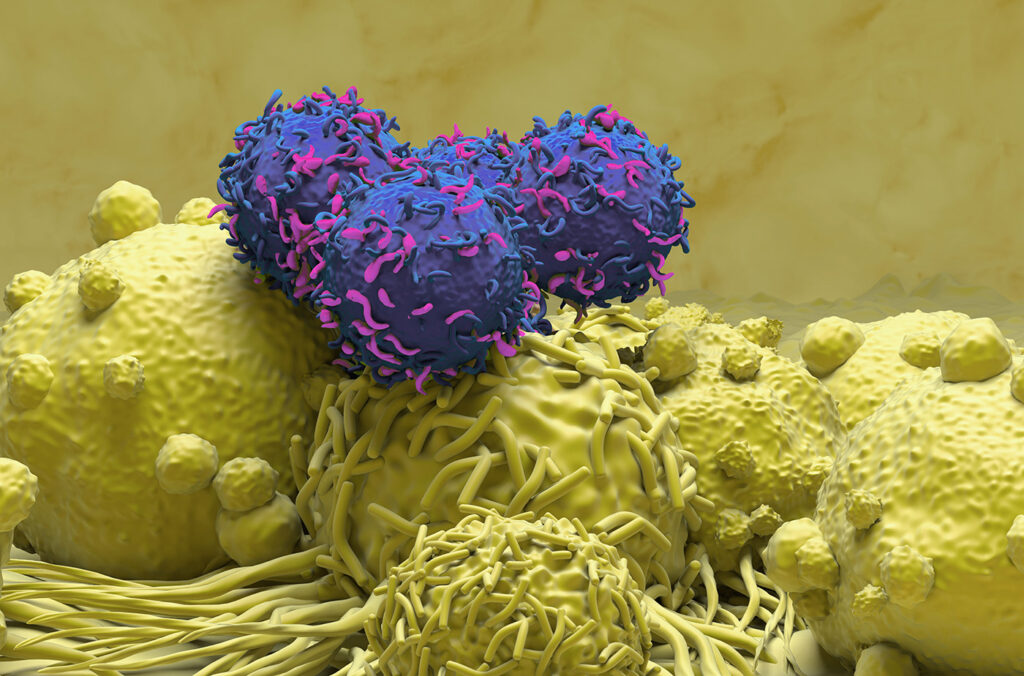

The team developed IL-12-producing CAR T cells that directly target and disarm these tumor-associated macrophages, opening the tumor’s gates for the immune system to then enter and wipe out the cancer cells. The researchers demonstrated that the CAR T cell therapy increased survival in aggressive preclinical models of metastatic ovarian and lung cancer, and suggest that results could point to a new strategy for treating advanced-stage solid tumors.

“This establishes a new way to treat cancer,” commented Brian Brown, PhD, director of the Icahn Genomics Institute, vice chair of Immunology and Immunotherapy, associate director of the Marc and Jennifer Lipschultz Precision Immunology Institute, and Mount Sinai professor of Genetic Engineering, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “By targeting tumor macrophages, we’ve shown that it can be possible to eliminate cancers that are refractory to other immunotherapies.”

Brown, together with co-senior author Jaime Mateus-Tique, PhD, a faculty member in Immunology and Immunotherapy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and colleagues described the study in Cancer Cell, in a paper titled “Armored macrophage-targeted CAR T cells reset and reprogram the tumor microenvironment and control metastatic cancer growth.” In their paper the scientists concluded that their findings, “… position IL-12–producing, myeloid-directed CAR T as a broad strategy to remodel the TME and drive anti-tumor immunity for solid cancers.”

Metastatic cancers cause the vast majority of cancer-related deaths, and solid tumors such as lung and ovarian cancer have proven especially difficult to treat using current immunotherapies. One major reason is that tumors actively suppress the immune system in the surrounding tumor microenvironment, creating a kind of protective fortress around the cancer cells. This has hampered development of CAR T cell immunotherapies targeting solid tumors.

“Even with cancer cell-restricted targets, CAR T’s face the challenge of the highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) in solid tumors, which is established, at least in part, by tumor associated macrophages (TAMs),” the authors wrote. In healthy tissues, macrophages act as first responders, fighting infection and helping to repair damage. Inside tumors, however, the macrophages are reprogrammed to do the opposite, blocking immune attack and helping cancer survive and spread.

“What we call a tumor is really cancer cells surrounded by cells that feed and protect them,” Mateus-Tique further explained. “It’s a walled fortress. With immunotherapy, we kept running into the same problem—we can’t get past this fortress’s guards. So, we thought: what if we targeted these guards, turned them from protectors to friends, and used them as a gateway to bring a wrecking force within the fortress.”

CAR T cells are generally designed to recognize and kill cancer cells, but for many types of cancers there are no good ways to make the CAR T cells do that. For their newly reported study the team designed CAR T cells to recognize and eliminate tumor-associated macrophages specifically—while sparing normal macrophages—and so convert the tumor from immune suppressed, to immune active. “TAMs provide an opportune target for CAR T not only because they are pivotal in establishing the immunosuppressive TME state, but also because TAMs express specific molecules, such as FOLR2 and TREM2, that are not expressed by most cells.”

Anti-TAM CAR T cells targeting either the TAM-specific markers FOLR2 or TREM2 were further engineered to produce a potent immune-activating molecule, interleukin-12, which is specialized at switching on killer T cells. The researchers used these IL-12-armored anti-TAM CAR T cells to treat mice carrying metastatic lung and ovarian cancers, with striking results. The treated animals surviving for months longer than control animals, and many of the CAR T cell-treated mice were completely cured.

To understand what was happening inside the tumors, the team used advanced spatial genomics techniques. These analyses showed that therapy reshaped the tumor environment, removing immune-suppressing cells and drawing in immune cells capable of killing the cancer. “Our data suggests that IL-12 armored anti-TAM CAR T promoted tumor clearance, at least in part, by facilitating an endogenous T cell response against the cancer cells,” the team wrote. “This is supported by the accumulation of proliferating, cytotoxic, and memory-like CD8 T cells in the tumors, and the expansion of cancer cell-reactive CD8 T cells.”

This is an important development because it makes the therapy ‘antigen-independent’ and has the potential to enable many different cancers to be treated, even ones not traditionally amenable to immunotherapy. The same treatment approach successfully treated both lung and ovarian cancers, which the researchers suggest highlights its potential as a broad cancer therapy.

“Macrophages are found in every type of tumor, sometimes outnumbering the cancer cells,” added Brown. “They’re there because the tumor uses them as a shield. What’s so exciting is that our treatment converts these cells from protecting the cancer to killing it. We’ve turned foe into ally.” The authors concluded, “Altogether, this work highlights the potential of IL-12 armored anti-TAM CAR T cells as a broadly applicable strategy to reset and reprogram the TME to a more immunostimulatory state and promote anti-tumor immunity and cancer clearance.”

The researchers stressed that human studies are needed to determine whether the approach will be safe and effective in patients. The results should not be viewed as a cure, but as proof of concept for a new immunotherapy strategy. The team is now working to refine the approach, particularly by tightening control over where and how IL-12 is released within tumors in mouse models. The goal is to maximize effectiveness while ensuring safety as the therapy moves closer to potential testing in humans. Beyond lung and ovarian cancer, the researchers believe the strategy could serve as a foundation for future CAR T therapies that reshape tumors by targeting their support cells rather than cancer cells alone.