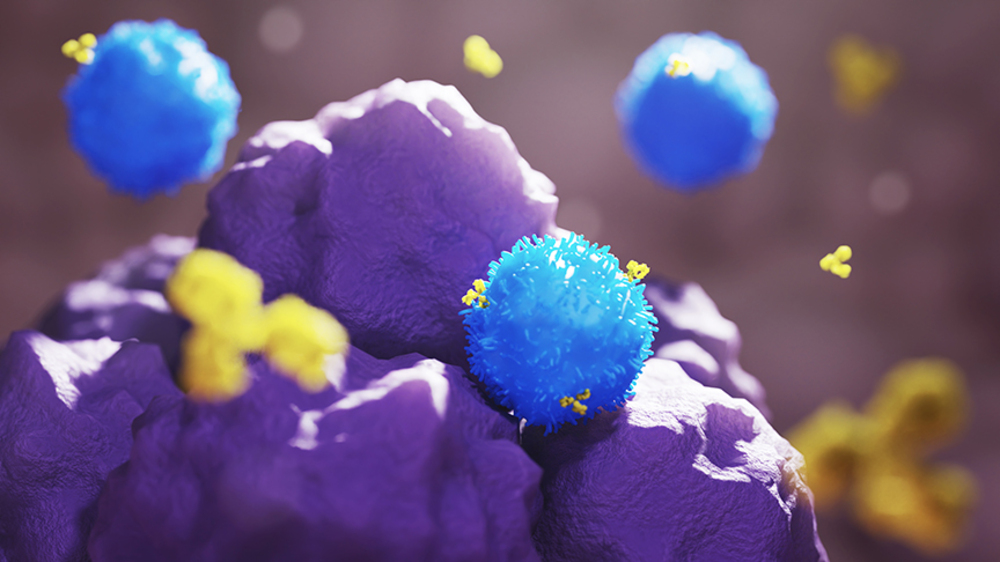

A specific immune response helps explain why only some cancer patients benefit from PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors, according to research from scientists at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The study was published in yesterday’s online issue of Nature Medicine. It shows that PD-1 therapy triggers a coordinated immune response where antibodies and T cells work together to fight cancer. It also points to IgG1 as a potential biomarker of response.

“Plasma cells producing IgG1 at the tumor site (both before and after treatment with PD-1 blockade administered before surgery to liver cancer patients) were predictive of better response (more tumor necrosis),” Sacha Gnjatic, PhD, told Inside Precision Medicine. He is professor of immunology and immunotherapy at the Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Center and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and corresponding author of the study.

He added that, “This was confirmed in a number of other internal and external studies with available datasets, beyond just neoadjuvant PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma.”

Immunotherapies have transformed cancer care and are now a backbone of treatment across many tumor types. The world market for these treatments is valued at approximately $140 billion now and is projected to reach over $300 billion by 2033. But not all patients experience durable benefit, and understanding the biological reasons behind this variability is one of the biggest questions in this field.

“While PD-1 therapies are often described as working exclusively through T cells, our data show that antibody-producing plasma cells (specifically those making IgG1 antibodies) are a critical part of the picture,” Gnjatic, said. “These cells appear to help coordinate a more effective, tumor-specific immune response.”

The Mount Sinai research team initially studied tumor and blood samples from 38 patients with liver cancer who received PD-1 therapy before surgery. Patients were considered responders if more than half of their tumor tissue was destroyed by treatment.

Using transcriptomic, proteomic, and computational tools they determined that tumors from responders contained more IgG1 plasma cells, especially during treatment. These cells showed signs of clonal expansion that were found circulating between tumor and lymph nodes, and shared with memory B cells—precursors to plasma cells.

Importantly, rather than relying solely on new B cells generated from scratch, PD-1 therapy appeared to expand (to divide, so that they are more prevalent) B cell clones that were already present before treatment, and these expanded cells were linked to better outcomes.

Blood samples from responders also contained IgG1 antibodies that recognized tumor-specific proteins, including cancer-testis antigens such as NY-ESO-1. These proteins are found mostly in cancer cells and not in healthy tissue. Patients with these antibodies also showed stronger tumor-targeting T cell activity, pointing to a coordinated and tumor-specific immune response.

To confirm their findings, the researchers analyzed data from seven additional clinical trials totaling more than 500 patients, including independent new datasets and previously published studies with PD-1 blockade across different diseases.

“Validating high-throughput findings using publicly available datasets offers the strongest evidence for identifying robust and reproducible markers of clinical response. This approach represents the true path to scientific progress as we develop and apply innovative algorithms,” said Edgar Gonzalez-Kozlova, PhD, assistant professor of immunology and immunotherapy at the Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Center and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The study also suggests that IgG1 plasma cells could become a biomarker to help predict which patients are most likely to benefit from immunotherapy. It also opens the door to new treatment strategies that boost tumor-specific antibody responses, such as cancer vaccines used alongside PD-1 therapy.

“Our long-term hope is that understanding the antibody landscape within tumors could help guide treatment decisions and reduce unnecessary exposure to therapies that may be unlikely to work for certain patients,” said Gnjatic.

Next, the research team plans to study this immune response in other cancers, including blood cancers such as multiple myeloma, and to better understand how antibodies in the blood are linked to plasma cells inside tumors.

For now, Gnjatic said, “Plasma cells should not be ignored when mapping tumor tissues for immune cell infiltration as a biomarker of prediction to immunotherapy. Longer term, this suggests that plasma cells could be harnessed or enhanced for better outcomes through approaches such as cancer vaccines.”