Researchers at Rutgers University have found that liver cancer can be driven in part by the liver’s failure to dispose of nitrogen waste and that reducing dietary protein may slow tumor growth in people whose livers are already impaired. In a study published in Science Advances, the team found that repressed expression of urea cycle enzymes (UCEs) impairs the functioning of the liver’s ammonia waste-handling machinery which then promotes tumor development by feeding metabolic pathways cancer cells rely on to thrive.

“If you have liver disease or damage that prevents your liver from functioning correctly, you should seriously consider reducing your protein intake to lower the risk of developing liver cancer,” said senior author Wei-Xing Zong, PhD, a distinguished professor at the Rutgers Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy and a member of Rutgers Cancer Institute.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common liver cancer, often develops in people with a chronic liver disease such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, often called fatty liver disease), where the organ’s metabolic functions are already compromised. Long-standing clinical observations have noted that patients with liver cancer frequently have elevated ammonia levels. Ammonia is produced when dietary protein is broken down, primarily by microbes in the gut. In healthy people, the liver then converts ammonia into urea through the urea cycle so it can be excreted.

“The clinical observation that the liver’s ammonia-handling machinery is usually impaired in liver cancer patients is decades old,” Zong said. “The question that has remained unanswered until now is whether this impairment and the resulting ammonia buildup are a consequence of the cancer or a driver of the tumor growth.”

For their work, the Rutgers team focused their research on UCEs. Prior studies have established correlations between reduced UCE expression, altered blood metabolites, and worse outcomes in patients with HCC, as well as links between ammonia metabolism and fatty liver disease. In addition, studies in mice have suggested that increased hepatic ammonia could promote liver cancer, but animal models that allowed direct testing of cause and effect were limited.

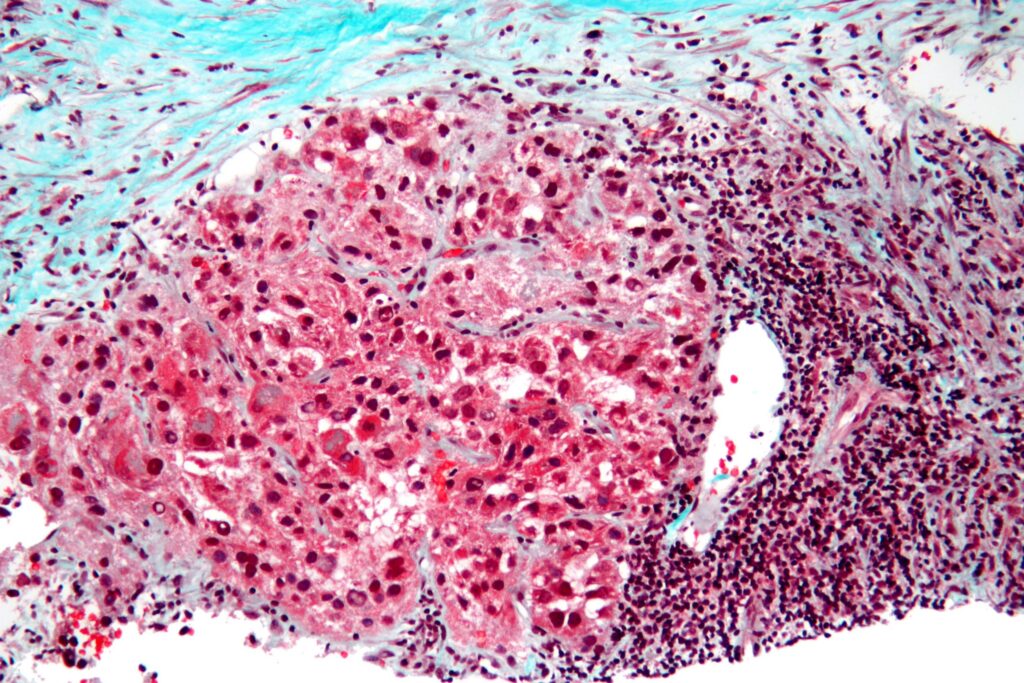

To address this, the researchers compared several commonly used mouse models of HCC and found that in models driven by oncogenic β-catenin, UCE expression was markedly reduced and ammonia levels rose as tumors developed. In a c-MET/sgAxin1 model, however, UCE expression remained largely intact. The researchers leveraged this finding to selectively silence individual UCEs via gene editing of the c-MET/sgAxin1 model in order to assess the effects of UCE loss.

Silencing enzymes such as Cps1, Ass1, Asl, or Arg1 in this model increased ammonia burden and accelerated tumor growth. “Silencing each of the UCEs… resulted in elevated ammonia burden, together with reprogramming of amino acid metabolism and pyrimidine synthesis, supporting a causative role of defective UC in promoting HCC,” the researchers wrote. The team further noted that mice with impaired ammonia disposal developed heavier tumor burdens and died sooner than those with functioning systems.

Employing untargeted metabolomics and nitrogen isotope labeling, the researchers showed that excess ammonia was incorporated into amino acids and pyrimidines, molecules needed for DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. “The ammonia goes into amino acids and nucleotides, both of which tumor cells depend on for growth,” Zong said.

After discovering this mechanism, the researchers then tested whether lowering the nitrogen load could blunt tumor growth. They fed mice with liver cancer a low-protein diet, providing about six percent of calories from protein, and compared them with animals on standard diets. Mice on the protein-restricted diet showed slower progression, lowered ammonia levels in their blood and liver, and survival increased survival in two different HCC models, pointing to the preventative effects of a low-protein diet.

These findings now highlight ammonia and urea cycle function as potential targets for clinical intervention, either through diet or future drugs designed to modulate nitrogen handling or downstream metabolic pathways such as pyrimidine synthesis. This understanding could also allow clinicians to closely monitor ammonia levels in patients at high risk of developing HCC.