Some types of CD8+ T cells (killer T cells) may play a role in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS). This is according to data from a new study published in Nature Immunology. Specifically, scientists found specific T cells that are abundant in people with MS, which also target the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). They suggest that this points to a possible role for the virus in triggering the immune response seen in the autoimmune disease.

Full details are published in a paper titled “Antigen specificity of clonally enriched CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis.” For Joe Sabatino, MD, PhD, senior author on the study and an assistant professor of neurology at University of California, San Francisco’s Weill Institute for Neurosciences, “these understudied CD8+ T cells [connect] a lot of different dots.” That is because scientists have known for several years that EBV, a common virus carried by about 95 percent of adults, is present in virtually everyone who develops MS. This data “gives us a new window on how EBV is likely contributing to this disease,” he said.

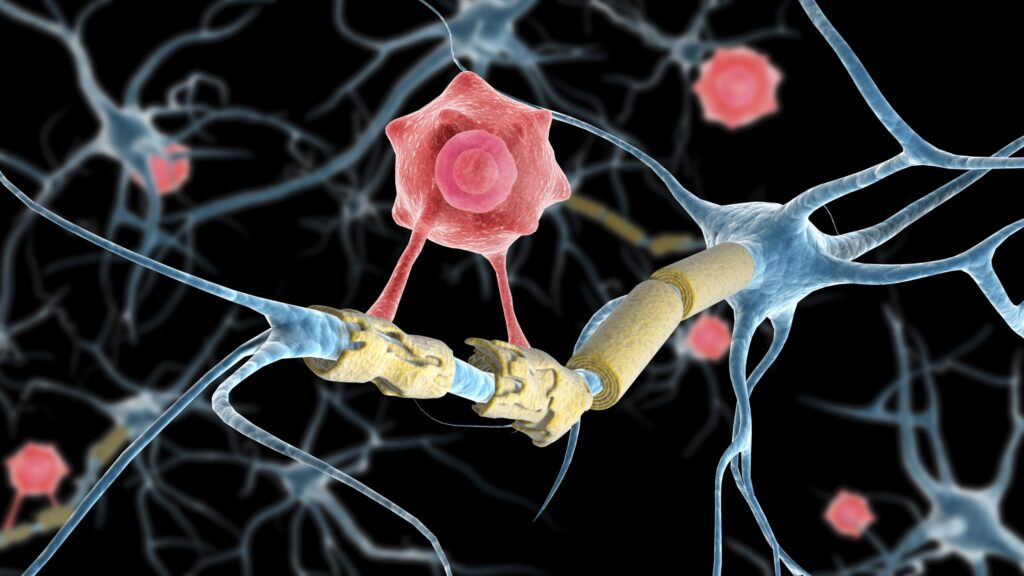

By way of background, MS develops when the immune system mistakenly attacks the myelin around nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord causing progressive neurological damage. Though CD8+ T cells are the “dominant lymphocyte population in MS lesions,” to date, MS research has largely focused on CD4+ T cells which coordinate immune response but do not directly kill cells. One study, for example, used a CD4+ T cell clone to identify an autoantigen that could be “an inducer or driver” of pathogenic autoimmune responses in MS. Another study linked autoproliferation of CD4+ T cells and B cells, seen in MS cases, to the HLA-DR15 haplotype, the main genetic factor associated with the disease.

For the study, Sabatino and his team used single-cell RNA sequencing and T cell receptor-sequencing to analyze killer T cells in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from people with early untreated MS and a control group. Specifically, they looked at CD8+ T cells that recognized specific proteins in each of these fluids. Participants without the disease had similar numbers of cells that recognized the proteins in both blood and CSF. In contrast, people with the disease had between 10 to 100 times more cells in the CSF than in blood. This difference points to something unusual taking place in the central nervous system that the immune system was responding to.

Furthermore, EBV was present in the CSF of most study participants, whether they had MS or not, according to the scientists, and some of its genes were active. One of these genes was only active in people with MS, suggesting that it may drive the overactive immune response characteristic of MS.

The findings are just the latest to implicate EBV in autoimmune disease. Along with MS, the virus has been linked to lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and long COVID-19. And some MS researchers have already begun testing therapies that target EBV. The exact “mechanism by which EBV is involved in MS pathogenesis remains unresolved,” however the findings reported here are an important step in the direction of possible new treatments. “The big hope here is that if we can interfere with EBV, we can have a big effect, not just on MS but on other disorders,” Sabatino said.