Since the landmark 2019 approval of Enhertu, the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) drug that quickly became a blockbuster breast cancer therapy—with global sales surpassing $1.6 billion in 2022—industry investment in ADC technologies has surged. ADCs marry the precision of antibody targeting with the tumor-killing power of cytotoxic drugs, offering a compelling strategy for delivering potent therapies directly to diseased cells.

Enhertu chemically links deruxtecan, a topoisomerase I (topo I) inhibitor, to trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively binds HER2—a protein essential for normal cell growth but overexpressed in many breast cancers. Topo I inhibitors are highly effective at destroying rapidly dividing cells characteristic of tumor progression, yet their lack of selectivity can also harm healthy tissue.

Today’s therapeutic companies are pushing ADC technology further by optimizing payload potency, improving linker chemistry, and even designing antibodies from scratch to transform clinical outcomes.

Cancer smart bomb

Kristen Buck, MD, executive vice president of R&D and chief medical officer at Lisata Therapeutics, a clinical-stage biotech focused on developing solid tumor therapies, notes that limited tumor penetration caused by a dense stromal barrier, along with a hostile tumor microenvironment (TME) that shields cancer from the immune system, has long hindered effective targeted drug delivery.

Lisata’s cyclic peptide, certepetide, addresses this gap by leveraging a naturally occurring endocytic pathway to promote lysosomal internalization of a drug. By enhancing tumor penetration, this “smart bomb” approach localizes cell death and minimizes the killing of healthy cells caused by the ADC bystander effect.

In a recent partnership, Lisata has incorporated certepetide as a payload in Catalent’s ADC technology platform. Results presented at the November 2025 World ADC San Diego conference demonstrated that using certepetide in combination with cytotoxic payloads both improved ADC efficacy and widened the distribution of the drug within the TME.

Buck emphasizes that ADCs have a higher therapeutic index than conventional cytotoxics, as they allow the delivery of very potent drugs directly to cancer cells, achieving antitumor activity at doses that would be too toxic if delivered systemically by venous injection. The combination therapy with certepetide has also shown promise for patients whose disease progression has stubbornly resisted standard treatments.

“By the time patients have had two or three lines of therapy, they often have limited treatment options,” she explained. “ADCs have shown meaningful clinical responses in patients who have been refractory to other lines of therapy. That’s hard to come by in my field.”

Beyond ADC conjugation, Buck also highlights that certepetide is versatile and can be administered in combination with any cancer drug, including PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Certepetide enhances the recruitment of cytotoxic T cells and inhibits regulatory T cells to strengthen the effects of these immunotherapies.

Improved degraders

To improve drug potency and selectivity, Thomas Pillow, PhD, distinguished scientist, discovery chemistry at Genentech, describes the company as an early pioneer for degrader-antibody conjugates (DACs), which carry proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) payloads that degrade specified proteins inside of cells.

Unlike inhibitor drugs, PROTACs do not require deep hydrophobic binding pockets or well-defined active sites, thereby greatly expanding the range of druggable targets. Additionally, as PROTACs are not consumed during the degradation process, a single molecule can repeatedly eliminate multiple disease-causing proteins, enhancing overall therapeutic potency.

Pillow highlights that DACs offer advantages over small-molecule therapeutics, including prolonged biological activity.

“You may want to target a protein with certain physicochemical properties that’s not amenable to an oral drug. Attaching the drug to an antibody can allow a longer half-life or efficacy that’s not achievable with a small molecule by itself,” he explained.

In contrast to in vivo administration of unconjugated PROTACs, DACs permit the delivery of degraders with poor drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMK) with improved targeting to specific tissues by using the antigen that is recognized by the antibody.

Results from Genentech’s seminal DAC work targeting the bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), a cancer-implicated epigenetic reader that controls gene expression for cell growth, showed that in vivo administration of the unconjugated PROTAC had no activity, despite being a highly potent degrader in cell culture. In contrast, a single IV dose of the DAC allowed sustained in vivo exposures with antigen-specific tumor reduction.1

“We demonstrated that you can take a molecule that is essentially inactive in vitro, and make it active in vivo using a DAC,” Pillow emphasized.

Choose your site

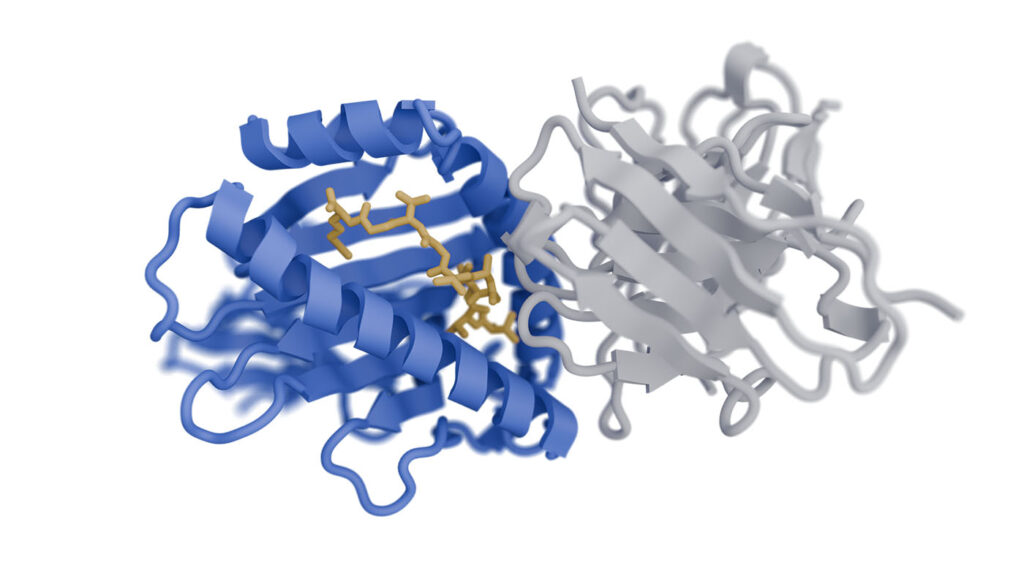

Rather than engineering new payloads, Michael Lukesch, PhD, CEO of VALANX Biotech, an Austria-based ADC company, is tackling heterogeneous ADC populations that contain variable drug-to-antibody ratios (DARs) and biophysical properties, including charge, stability, and aggregation. Caused by random payload attachment, these mixtures can lead to premature payload release, off-target effects, and diminished therapeutic efficacy.

To address this challenge, VALANX uses non-canonical amino acids to enable site-specific conjugation of cytotoxic drugs. As conventional methods have relied on abundant cysteine and lysine residues for conjugation, this genetic code expansion approach opens design space to hundreds of sites and enhances the therapeutic window by enabling higher dosing with reduced toxicity.

“We found sites where we can hide the payload in the antibody structure from external interaction to achieve an improved target profile, so that the ADC only releases the payload when bound to the cancer cell,” explained Lukesch.

Taken together, Lukesch looks forward to more readouts describing ideal ADC features that remain under debate in the field, including linker design, payload engineering, and sequential antibody treatments.

“Collecting these different data points in the next couple of years will make ADC development more efficient and meaningful in the clinic,” he said.

De novo rise

In AI, rising start-ups are ushering in a wave of drug discovery in which antibodies are crafted from scratch or de novo. The new approach of AI-guided rational design bypasses the need for traditionally labor-intensive and time-consuming experimental screens, which lack the atomic precision needed to control therapeutic effect.

Surge Biswas, PhD, CEO of Nabla Bio, sees a future in which users can specify binding to a particular set of atoms on a target and generate a corresponding antibody that satisfies those constraints. The Boston-based AI protein therapeutics company spun out of the lab of George Church, PhD, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and prolific biotech entrepreneur.

In October, Nabla announced Joint Atomic Model-2 (JAM-2), a molecular design model that generates de novo antibodies with nanomolar affinities and developability metrics comparable to late-clinical stage or FDA-approved antibodies.

Across 28 structurally and functionally diverse targets, JAM-2 achieved double-digit hit rates from small design sets, a significant advance over traditional methods where success rates land at less than one percent. Difficult targets hit by JAM-2 include G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a large protein family that represents approximately one-third of drug targets but are historically difficult to hit, given that the druggable regions barely protrude from the membrane.

“This technology is ready for prime time and should be a first-line approach in drug discovery campaigns, alongside other tried and tested approaches, such as immunization, and phage and yeast display,” said Biswas.

In November, Nabla announced a multi-year research collaboration with Takeda to apply the company’s AI platform across Takeda’s early-stage development programs, including de novo antibodies, multi specifics, and other custom therapeutics. Nabla is granted eligibility to receive success-based payments reaching upwards of $1 billion. Biswas highlights that JAM-2 is an indication-agnostic and horizontal technology that makes sense to be applied over multiple programs in parallel.

Concurrently last fall, Chai Discovery, an OpenAI-backed AI drug developer, announced de novo antibody design model, Chai-2, which was reported to achieve an equally impressive 16% success rate for a small sample size of only 20 antibodies or nanobodies to 52 diverse targets.

Josh Meier, co-founder and CEO of Chai, said the original pitch to Series A investors was to achieve a one percent success rate, a “transformative” improvement on traditional methods that could funnel more drug candidates into functional tests. Those expectations were blown out of the water with double-digit results.

Co-founder, CEO, Chai Discovery

“If you asked people earlier this year, ‘At what point would you see de novo antibody design working?’ many thought we were five years out,” said Meier in an interview with GEN at the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) conference in San Diego earlier this month. “We published our results two weeks after we had some of those conversations and went back to those folks to say this is actually working today.”

Biswas states that seeing multiple groups release de novo work lends credence to the achievement of the field. “It’s harder to believe that this is working if only one company is publishing. Multiple companies showing evidence demonstrates that these advances are real and coming quickly.”

“We’re not going to stop until we get full drug candidates out of the models. Given the results we’re seeing, it’s possible that we actually get there in the near future,” weighed in Meier.

References

Pillow TH, Adhikari P, Blake RA, et al. Antibody Conjugation of a Chimeric BET Degrader Enables in vivo Activity. Chem Med Chem 2020;15(1):17–25.