Researchers at Case Western Reserve University, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh, say they have developed a method to enhance natural killer (NK) cells taken from people living with HIV to target reservoirs of the virus that remain dormant in the body despite daily antiretroviral therapy (ART). The study, published in mBio, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology, detailed the development of enhanced NK (eNK) cells which one day may reduce or replace daily ART dosing by boosting the immune system to provide long-term control of the virus.

“NK cell immunotherapy is already being used for cancer therapy, and the data from those studies provides a great foundation for translation of this approach to an HIV cure strategy,” said lead author of the study Mary Ann Checkley-Luttge, PhD, a senior research associate at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. “We are hoping that NK cell immunotherapy can help reduce the reservoir enough to allow long-term immunological control of HIV without ART.”

Currently, the standard treatment for treating HIV is ART which reduces HIV in the blood to nearly undetectable levels but does not eliminate the virus. HIV persists in reservoirs found mostly in infected CD4+ T cells that remain hidden from immune activity when viral genes are not actively expressed. But if treatment stops, the virus will re-emerge. Strategies seeking to eradicate the virus have, to date, focused on latency-reversing agents. But these efforts have been hampered by inefficiencies in reactivating the virus and adaptive immune responses. Further, clinical and laboratory studies have shown that strategies to coax the virus out of latency do not effectively reduce the reservoir size.

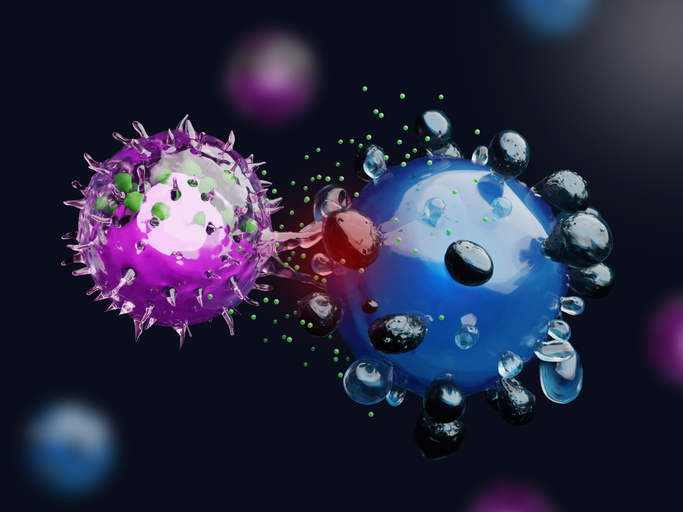

For this research, the team looked to NK cells as a potential solution. These cells, which are a part of the innate immune system, are specialized to recognize and kill virus-infected or tumor cells without relying on antigen-specific receptors. Unlike T cells, NK cells can detect the balance of activating and inhibitory signals on target cells. HIV infection alters this balance by downregulating major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and increasing stress-related ligands, which makes infected cells susceptible to NK cell recognition and elimination. It is these properties that interested the Case Western team to assess whether NK cells could be used to eliminate HIV-infected cells.

The researchers found clues to the potential of using NK cells as a treatment against HIV. For instance, earlier work has shown the broad neutralization of antibodies against HIV.

Prior research suggested several pieces of this strategy. Broadly using neutralizing antibodies against HIV has been shown to suppress the amount of virus circulating in the blood and delay viral rebound, in part by triggering antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Further, adoptive NK cell therapies have already been successfully developed for treating cancer, demonstrating that NK cells can be safely expanded to large numbers and infused into patients.

In the new study, the team expanded NK cells from the blood of people living with HIV (PLWH) who were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Using artificial antigen-presenting cells expressing membrane-bound interleukin-21, they generated a population of enhanced NK cells, or eNK cells. “We demonstrate that NK cells from PLWH can be expanded outside the body into ‘eNK’ cells that specifically attack HIV-infected cells without harming uninfected ones, significantly reducing HIV reservoirs in vitro after LRA treatment,” the researchers wrote.

For their work, the researchers combined eNK cells with latency-reversing agents, including vorinostat and interleukin-15 or an IL-15 superagonist. Reactivating latent HIV made infected CD4+ T cells visible to the immune system which then allowed the eNK cells to kill the reactivated virus.

To assess how effective this technique was, the investigators gathered data on multiple indicators of reservoir size, including proviral DNA, inducible HIV RNA, and virus release. Their analysis showed consistent declines across these measures after treatment with eNK cells.

The research demonstrates the promise of immune-based strategies to create drug-free remission opposed to complete viral eradication. By reducing the size of the latent reservoir, eNK cell therapy could make it possible for some individuals to stop antiretroviral therapy without the risk of viral rebound, or to decrease the need for daily ART dosing. The work also show which latency-reversing agents may be compatible with NK cell–based approaches, since the researcher showed that some of the latency-reversing compounds also reduced NK cell cytotoxicity in vitro.

The researchers are now eyeing advancing this strategy beyond preclinical lab studies. “Our team’s next goals are to test whether lab-enhanced NK cells can work as ‘off-the-shelf’ therapy,” said senior author Jonathan Karn, PhD, director of the Center for AIDS Research at Case Western Reserve. “We plan to conduct studies using advanced animal models that closely mimic HIV infection in humans and then work toward clinical trials in the next two years to test this approach in people living with HIV.”