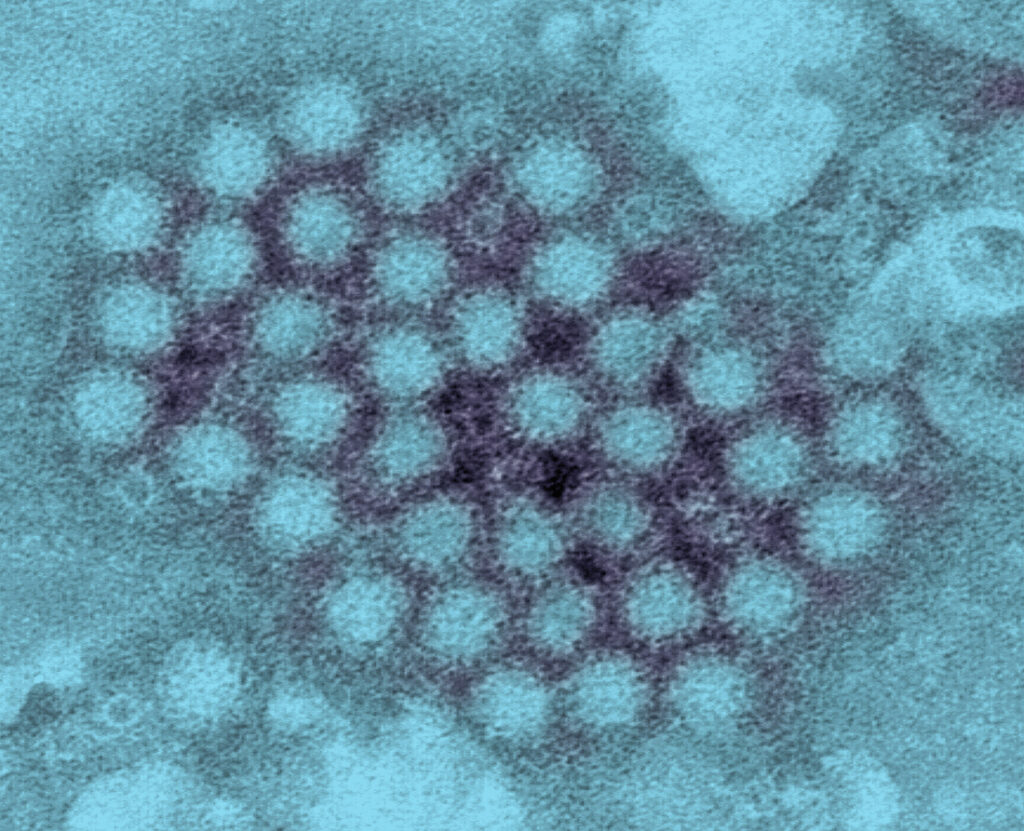

Human norovirus (HuNoV) is a leading cause of acute viral gastroenteritis worldwide, causing symptoms ranging from discomfort to severe outcomes in young children, the elderly, and people who are immunocompromised. While its spread is common, effective treatment and preventative strategies are lacking due to the difficulty in cultivating the virus in laboratory settings.

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, led by Mary Estes, PhD, worked with intestinal organoids, specifically human intestinal enteroids (HIEs), to identify why the growth of norovirus in culture stops and to determine methods to maintain growth.

Typically, norovirus samples are collected from infected individuals via stool samples. Obtaining samples for research, and eventually for scale-up, is a challenge as resources are limited and inconsistent. Growing norovirus in the lab would address this limitation for both norovirus research and therapy development.

“Looking to overcome this obstacle, we studied several versions of HIEs to understand why norovirus growth usually stops,” said co-author Sue Crawford, PhD, assistant professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor.

The research was published in Science Advances in a paper titled, “Overcoming host restrictions to enable continuous passaging of GII.3 human norovirus in human intestinal enteroids.”

“In 2016, a previous breakthrough occurred when scientists in our lab and collaborators successfully grew HuNoV in HIEs, or ‘mini-guts’—miniature, lab-grown versions of the human gut,” said first author Gurpreet Kaur, a graduate student in the Estes lab.

“While this system allowed researchers to infect cells and study the virus, it still had a major shortcoming—the virus would not grow through repeated rounds, the way scientists can grow many other microorganisms,” Kaur continued, “After just a few rounds, norovirus replication would stop, making it impossible to build up long-lasting viral stocks.”

Previous work on HIEs suggested that serial growth of the virus is hindered by host-limiting mechanisms that are still undetermined. The team conducted RNA sequencing experiments in multiple infected HIE lines to evaluate intestinal epithelial responses to HuNoV infection.

“Using RNA sequencing, a method that measures gene activity, we discovered that infected HIEs produced high levels of chemokines, molecules that help the body mount an immune response. Three chemokines stood out: CXCL10, CXCL11, and CCL5,” said Crawford.

The team followed up this discovery by investigating whether blocking the chemokine signals would improve replication in the HIEs. “We tested a drug called TAK 779, originally developed to block chemokine effects,” said Kaur. “When TAK 779 was added to the HIE cultures, norovirus replication increased dramatically—virus spread throughout the cells in the cultures, and we achieved replication for 10 to 15 consecutive passages.”

This breakthrough opens the door to more effective study of norovirus. Crawford was optimistic in this outcome, stating, “TAK 779 allowed us to generate consistent batches of infectious virus from lab cultures instead of human stool—something we and other researchers have been seeking for decades.”

As useful as this finding is, the team also found that TAK 779 is not a ubiquitous solution, as not all HuNoV strains responded positively. “We observed that TAK 779 did not enhance replication of GII.4 strains, the most common cause of human outbreaks,” said Estes.

While TAK 779 targets chemokine response in many strains, enhancing replication of strain GII.3, and the growth of strains GII.17 and GI.1, other strains, including GII.4, showed no effect. GII.4 noroviruses don’t normally trigger chemokine secretion, thus there is no response to block with TAK 779, suggesting another mechanism that is limiting growth of these strains in lab settings.

There is still hope from the team as Estes points out that her lab is “currently optimizing our HIE culture conditions to enable efficient passaging of additional HuNoV strains, including GII.4.”

While there is still much work to be done to develop continuous cultivation of norovirus strains, this work has opened the door to the possibility of developing stable viral stocks happening sooner rather than later. With stable stocks of norovirus, improved access can speed timelines for the development of vaccines, antivirals, and other therapies to aid in the treatment of norovirus.