A new study is reshaping how researchers think about the earliest steps of pancreatic cancer progression, revealing that sympathetic nerves and cancer-associated fibroblasts collaborate far earlier than expected to fuel disease growth.

In work published in Cancer Discovery, investigators from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and colleagues show that in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), dense sympathetic nerve infiltration is already present at the stage of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN)—microscopic, pre-malignant lesions that precede invasive cancer. Rather than being passive bystanders, specialized fibroblasts appear to orchestrate this neural remodeling and then amplify its downstream effects.

“We were not expecting that,” said Jérémy Nigri, PhD, first author on the study. “People have studied perineural invasion—when cancer cells grow along nerves—as something that happens late in disease. But what we’re seeing is intense neo-innervation already at the PanIN stage.”

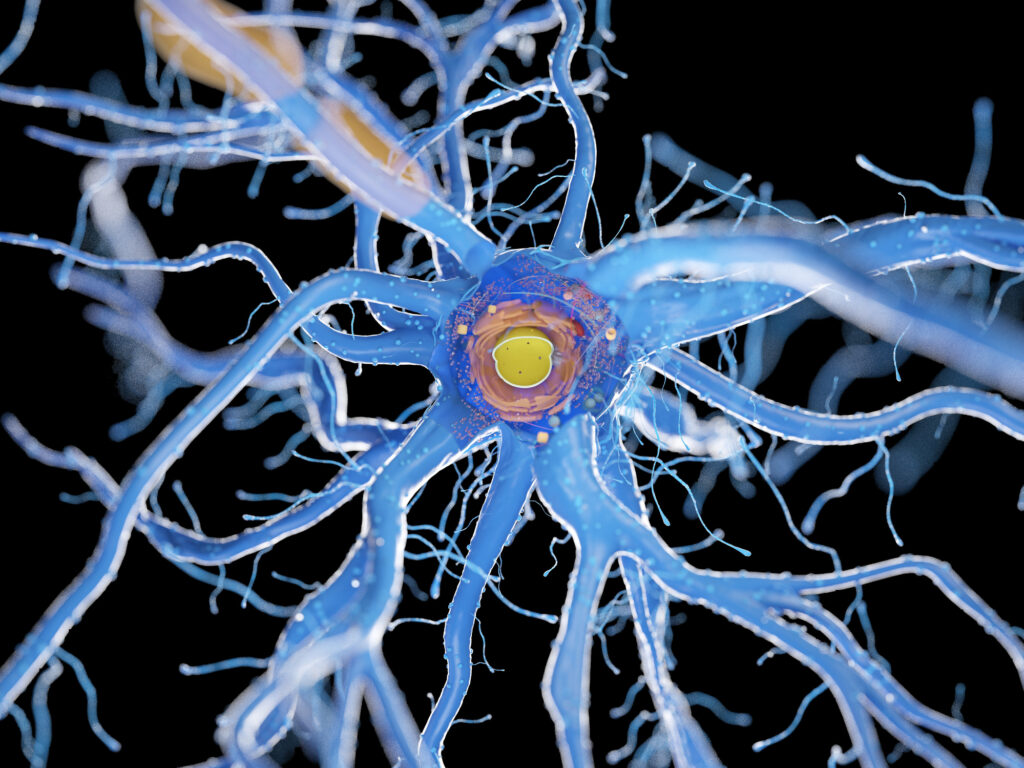

A 3D view of early lesions

PanIN lesions arise after early genetic alterations, such as KRAS mutations, but before full malignant transformation, which typically requires additional hits, such as TP53 loss. Using three-dimensional imaging of thick, cleared pancreatic tissue sections, Nigri and colleagues were able to visualize these early lesions in unprecedented detail.

“In two dimensions, you just see flat sections. You don’t really imagine how it looks in three dimensions,” Nigri said. “But now you see that it’s like a ball, and around it you have a shield of fibroblasts.”

Those fibroblasts resemble myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts (myCAFs), a stromal subtype typically associated with established tumors. Although the term “myCAF” is generally reserved for tumor settings, Nigri noted that “we saw a very similar phenotype in early lesions. And then we saw also a very similar phenotype in pancreatitis.”

Fibroblasts recruit the nerves

The study identifies transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β), produced during inflammation and neoplasia, as a driver of myofibroblast formation. These activated fibroblasts then secrete axon guidance molecules—proteins that attract sympathetic nerve fibers into the tissue.

“The first part of the paper is to show that these axons are coming into the tissue in part because of these fibroblasts,” Nigri explained. “They secrete molecules that we call axon guidance molecules, so they are attracting the nerves.”

This dense “neo-innervation” at an early, pre-invasive stage suggests that the neural microenvironment is being established well before cancer cells invade nerves.

Nigri proposes that this early nerve recruitment may prime the tissue for later perineural invasion. “Once the nerves are within the tissue, the cancer cells that acquire additional mutations can use these axons to migrate,” he said.

A feed-forward loop

The relationship is not one-sided. Once sympathetic nerves infiltrate the tissue, they release norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that signals through adrenergic receptors.

The team found that norepinephrine activates fibroblasts via the α1-adrenergic receptor and downstream Gαq signaling. This activation drives pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory programs, further enhancing stromal remodeling.

“So then the second part is that once these nerves are within the tissue, they also impact the fibroblasts,” Nigri said. “Norepinephrine is able to impact the activation of the fibroblasts and make them hyperactivated. We create kind of a loop—it will attract more nerves, and all of this can feed tumor growth and inflammation.”

In mouse models, sympathetic nerve depletion reduced stromal activation and decreased tumor growth by nearly 50%. Tumors in nerve-depleted animals showed markedly less fibrosis and collagen deposition.

“When we ablate the sympathetic nervous system, you almost have like 50% decrease of the tumor growth, which is a lot,” Nigri said. “And when we do that, the tumor changes in terms of histology—we have less fibrosis, less collagen.”

In complementary chemogenetic models, direct activation of fibroblast Gαq signaling was sufficient to exacerbate pancreatitis, accelerate acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM), and promote PanIN formation and tumor growth.

“When we activate the fibroblasts to mimic this downstream signaling of the alpha-1 receptor, you really exacerbate the pancreatitis,” Nigri said. “You get a severe pancreatitis. It means these fibroblasts have a huge impact on tissue remodeling.”

Therapeutic opportunities—and challenges

The findings point to several potential intervention points, including blocking α1-adrenergic signaling in fibroblasts or preventing nerve recruitment by targeting axon guidance molecules or myofibroblast formation.

“We can act with inhibitors of the adrenergic receptors we found implicated in fibroblasts,” Nigri said. “It’s called alpha-1 adrenergic receptor. We can block alpha-1.”

However, he cautioned that adrenergic receptors are widely expressed, raising concerns about off-target effects. “It’s always a balance between the benefits and the secondary effects of a drug,” he said. “Chemotherapy also affects normal cells, but if it affects the tumor more, it’s beneficial.”

Another strategy could involve intervening earlier in the cascade—for example, by preventing myofibroblast formation and thereby limiting nerve recruitment. “If we block this fibroblast formation, maybe they will not attract nerves in,” Nigri said.

From a clinical standpoint, identifying patients at the PanIN stage remains a challenge. But the broader conceptual advance may lie in expanding therapeutic focus beyond malignant epithelial cells.

“I think our paper shows that focusing only on the cancer cell is not the only solution,” Nigri said. “We should maybe target multiple cell types at the same time.”

Bridging oncology and neuroscience

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking the nervous system to cancer progression. While sympathetic signaling has been implicated in colorectal cancer, the receptor pathways appear to differ by tumor type.

Importantly, Nigri sees this work as part of a broader convergence of disciplines.

“Until recently, nobody cared about the nerves,” he said. “But now there are tools more available, and there is easier cross talk between neuroscience and oncology. The bridge between immunology, oncology, and neuroscience will be very important in the future.”

In PDAC—a malignancy defined by a dense desmoplastic stroma and notoriously resistant to therapy—understanding these neuro-stromal feedback loops could open new avenues for combination strategies that disrupt the tumor-permissive microenvironment.

By identifying the TGF-β–myofibroblast–sympathetic nerve axis and fibroblast α1-adrenergic signaling as actionable mediators of disease progression, the study reframes pancreatic cancer not simply as a genetic disease of epithelial cells, but as a complex, multicellular ecosystem—one in which nerves and fibroblasts are active architects of malignancy.