Researchers at Case Western Reserve University have discovered genetic mutations in a gene that place people at higher risk of developing Barret’s esophagus, a condition that greatly increases the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. The study, published in Nature Communications, found that the gene VSIG10L is a regulator of esophageal homeostasis and that mutations in this gene can weaken the esophageal lining and increase susceptibility to Barrett’s esophagus (BE) via a mechanism linking impaired epithelial maturation to bile acid-induced injury.

“We found that this gene acts like a quality control system for the esophageal lining,” said lead researcher Kishore Guda, PhD, an associate professor at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. “When it’s defective, the cells do not mature properly and the protective barrier in the esophageal lining becomes weak, allowing stomach bile acid to cause tissue changes that enhances the risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus.”

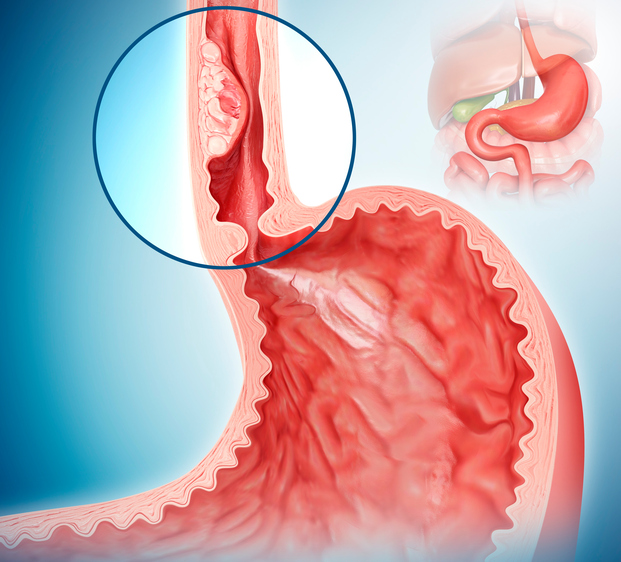

Barrett’s esophagus is characterized by intestinal-type mucinous metaplasia of squamous epithelial cells in the distal esophagus. In BE, the normal squamous lining of the food pipe is replaced by cells similar to those found in the intestinal lining. BE affects about five percent of the population nationally and is largely tied to people with chronic heartburn. Risk factors for BE include age, male gender, Caucasian ethnicity, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and diet. While all of these conditions have been linked to G, “they lack sufficient predictive power to guide effective clinical management of this disease,” the researchers wrote.

Prior work from the Case Western team had established a familial component to BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma with as many as 10% of patients reporting a family history of the condition. Their analyses suggested dominant transmission of incompletely penetrant Mendelian alleles. The team previously identified the first inherited autosomal dominant BE susceptibility variant, S631G, within the immunoglobulin-like domain of VSIG10L. In this new study, the researchers sought to find the extent of VSIG10L susceptibility variants across a larger cohort of BE and esophageal cancer with family links.

For this work, the researchers sequenced and analyzed genetic material from 684 individuals in 302 families in which multiple members had developed BE or esophageal cancer. The data generated from genetic sequencing revealed that a subset of affected family members carried inherited mutations in VSIG10L. Loss of gene expression was observed frequently in patients with chronic GERD, a known risk factor for BE.

To test causality, the team created mouse models that carrying human-orthologous germline mutations in Vsig10l. These models showed loss of desmosomes and disrupted epithelial differentiation programs in the squamous mucosa and when they were exposed long term to a bile acid–supplemented diet containing deoxycholate, the mutant mice developed overt BE-like lesions in the forestomach. According to Guda, the esophageal lining in these mice became disrupted structurally and molecularly, and bile acid exposure replicated disease progression as seen in humans. The model is the first animal system for BE based directly on human genetic predisposition.

“Our prior and current studies on VSIG10L in human tissues, relevant ex vivo/in vitro models, and Vsig10l-mutant mice now provide strong evidence underscoring its essential role in maintaining SQ maturation and integrity, and per se point to the likely pathogenic role of FBE-associated VSIG10L genetic variants,” the researchers wrote. The investigators also noted that pathology in mice similar to BE occurred only in the presence of deoxycholate, pointing to disruption of squamous homeostasis making the mice susceptible to chronic reflux injury. “Taken together, our findings suggest a plausible hypothesis where a perturbation in SQ homeostasis, much like that observed in GERD, may be one of the key initial processes in the development of BE,” the researchers wrote.

The newly identified genetic variants appear to drive processes governing epithelial differentiation, desmosome formation, and barrier integrity in suprabasal squamous cells. Inherited defects in VSIG10L disrupt epithelial maturation and homeostasis, rendering the mucosa more prone to reflux injury or abnormal healing. In individuals without this predisposition, homeostasis is often restored after injury. In patients at risk based on their genetic profile, however, GERD-induced damage combined with VSIG10L disruption and additional alterations may promote metaplasia and progression along a metaplasia-dysplasia-cancer sequence.

The identification of VSIG10L as a susceptibility gene provide an opportunity for clinicians to more clearly identify familial susceptibility to BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma via genetic sequencing.

“Knowledge gained from studying such familial aspects of disease will enable us to rapidly translate these findings into the clinic,” Guda said. “We can now conduct early screenings and develop preventative strategies before the disease develops, ultimately restoring patients’ quality of life and curtailing cancer deaths.” The researchers also noted that discovery of genes involved in BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma predisposition “should provide critical molecular insights into metaplasia-dysplasia-cancer progression, identify targets for developing chemopreventive/therapeutic drugs, and enable development of genetic tests for early screening for BE/EAC susceptibility.”