Researchers have engineered a new type of light-based nanosensors that can be programmed to detect extremely low concentrations of a wide range of biomarkers. In a study published today in the Optica journal, the sensors were capable of spotting a lung cancer biomarker in blood samples even when only a few molecules are present, showing promise for early cancer detection when biomarker levels are too low to be found using conventional methods.

“Our sensor combines nanostructures made of DNA with quantum dots and CRISPR gene editing technology to detect faint biomarker signals using a light-based approach known as second harmonic generation (SHG),” said Han Zhang, PhD, distinguished professor and director of the College of Physics and Optoelectronic Engineering in Shenzhen University. “If successful, this approach could help make disease treatments simpler, potentially improve survival rates and lower overall healthcare costs.”

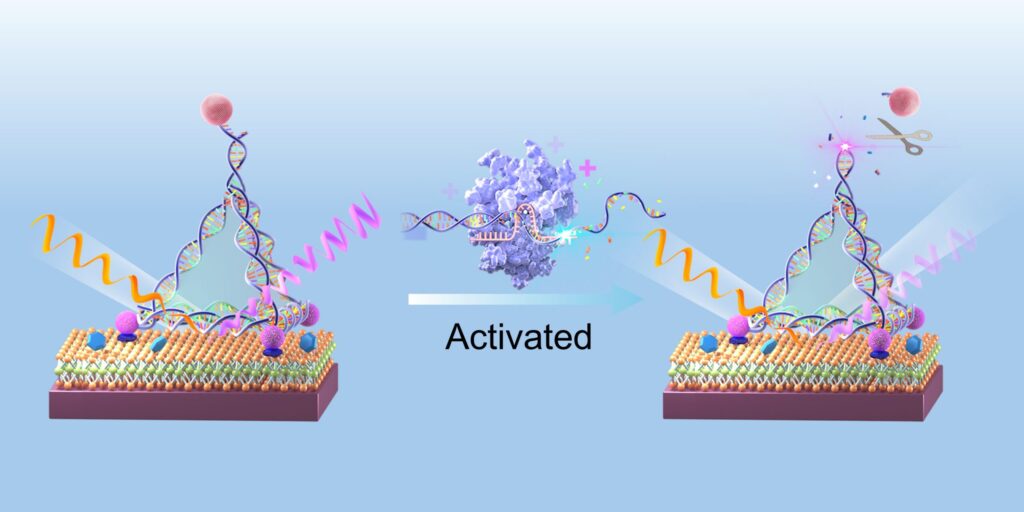

The sensors are made of a flat layer of molybdenum disulfide, a semiconducting material with ideal properties to support SHG—an optical phenomenon that reduces by half the wavelength of incoming light. Using DNA nanostructures shaped like pyramids, the scientists tethered quantum dots at precise locations on the sensor’s surface, enhancing the strength of the SHG signal produced.

With CRISPR, the sensor can be programmed to recognize any desired target. When the Cas12a protein recognizes its target, it cuts the DNA structures holding the quantum dots in place, reducing the SHG signal. Because of the minimal levels of background noise achieved with this setup, the sensor is able to accurately pick up very low concentrations of the target biomarker.

“Instead of viewing DNA only as a biological substance, we use it as programmable building blocks, allowing us to assemble the components of our sensor with nanometer-level precision,” said Zhang. “By combining optical nonlinear sensing, which effectively minimizes background noise, with an amplification-free design, our method offers a distinct balance of speed and precision.”

Unlike conventional detection methods that require the amplification of the DNA or RNA target in order to get a strong enough signal, these quantum sensors can directly detect their target even at ultra-low concentrations. This technology could therefore make workflows much faster and affordable while preventing potential errors introduced by complex amplification workflows.

Zhang and colleagues tested their sensor design by programming it to detect miRNA-21, a microRNA biomarker linked to lung cancer growth and metastasis. In serum samples obtained from lung cancer patients, the quantum sensor successfully picked up on the presence of the target biomarker.

“The sensor worked exceptionally well, showing that integrating optics, nanomaterials and biology can be an effective strategy to optimize a device,” said Zhang. “The sensor was also highly specific—ignoring other similar RNA strands and detecting only the lung cancer target.”

Going forward, the team plans to continue improving the sensor design and making it smaller, with the ultimate goal of developing a portable device that can be easily used both in clinical settings and remote locations to support early cancer detection.

“For early diagnosis, this method holds promise for enabling simple blood screenings for lung cancer before a tumor might be visible on a CT scan,” said Zhang. “It could also help advance personalized treatment options by allowing doctors to monitor a patient’s biomarker levels daily or weekly to assess drug efficacy, rather than waiting months for imaging results.”