PD-AGE roadmap calls for older, standardized preclinical models to better reflect the biology of an age-driven disease.

A new roadmap published in npj Parkinson’s Disease is asking a deceptively simple question: what if we allowed our models of Parkinson’s disease to age? Developed by the PD-AGE consortium with support from The Michael J Fox Foundation, the paper lays out practical guidance for integrating aging biology into preclinical Parkinson’s research – from model selection to standardized endpoints – with the aim of improving translational reliability.

An estimated one million Americans live with Parkinson’s, with global numbers exceeding ten million and rising as populations age. The disease remains tightly linked to advancing age, yet much of the field’s mechanistic and therapeutic work has relied on young animals and rapid-onset toxin paradigms. The authors argue that this mismatch between disease epidemiology and experimental design may be limiting insight and slowing progress [1].

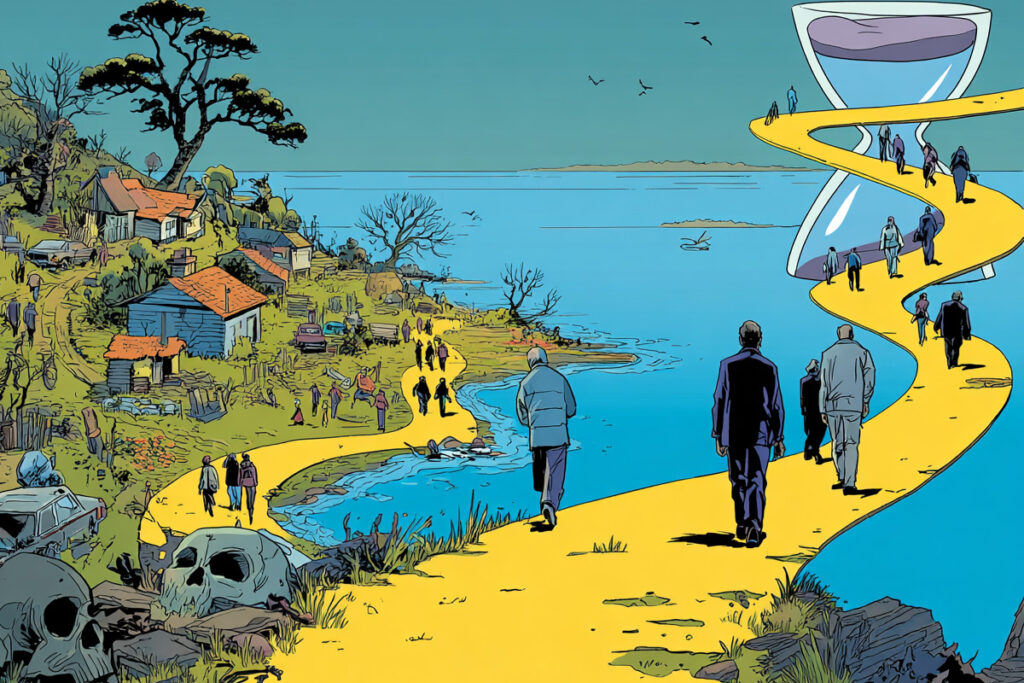

Longevity.Technology: Parkinson’s disease has always carried an awkward truth in plain sight: age is its greatest risk factor, yet much of our preclinical modeling still relies on animals that have barely reached middle age. The PD-AGE roadmap feels less like a radical departure and more like a long-overdue course correction – an insistence that if we are serious about translation, we must take aging biology seriously in the models that underpin it. That means favoring subtle, incomplete-penetrance genetic systems over abrupt toxin paradigms; allowing mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired autophagy and neuroinflammation to evolve over time rather than be chemically detonated; and, crucially, testing “second hit” hypotheses by crossing prioritized Parkinson’s models with accelerated aging strains to see what actually synergizes. The emphasis on tiered endpoints – beginning with whether dopaminergic neurons and their projections are actually being lost and whether α-synuclein pathology is accumulating – may not sound glamorous, but standardization is often the quiet accelerant of progress. Aging is slow, complex and expensive to model; ignoring it is slower still. If we continue to interrogate an age-driven disease in biologically youthful systems, we risk optimizing for a version of Parkinson’s that patients never experience. For a field increasingly fluent in the language of geroscience, this roadmap is a reminder that the real test is not rhetoric, but whether we are prepared to let our models grow old.

Rebalancing model choice

Julie Andersen, PhD, professor at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and a senior author of the paper, argues that the field must rethink its framing. “The research community needs to approach this disease holistically and aging is the place to start. Aging biology is emerging as a therapeutic target,” she said.

Central to the roadmap is a shift in experimental philosophy. Rather than relying predominantly on acute toxin models that induce rapid dopaminergic neuron loss, the authors recommend greater use of genetic models with incomplete penetrance and gradual phenotypes – systems that allow age-dependent processes to unfold. Parkinson’s, they note, “is a multifactorial disorder with a long prodromal phase,” and models should reflect that temporal complexity [1].

The consortium prioritizes models that display vulnerability without immediate collapse; animals in which mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired autophagy and inflammatory signaling can accumulate over time. It also advocates combining established Parkinson’s models with accelerated aging strains to operationalize the so-called “second hit” hypothesis – testing whether aging biology amplifies disease-relevant pathology rather than assuming it does.

As the authors write, “aging-related biological changes may interact with PD-associated mechanisms to influence disease onset and progression,” an interaction that remains underexplored in conventional paradigms [1].

Reviewing the available literature, Andersen said the team found that “the influence of aging on Parkinson’s is subtle, emerges gradually and likely interacts synergistically with other contributing factors.”

From endpoints to evidence

The roadmap goes beyond model selection to address measurement. The paper recommends a tiered approach to endpoints, beginning with the fundamentals – are dopaminergic neurons and their projections actually being lost and is α-synuclein pathology building – before escalating to more elaborate phenotyping that fewer labs can afford, and fewer still can reproduce.

Standardization is a recurring theme. The authors emphasize harmonized protocols and comparable readouts across laboratories to improve reproducibility and reduce noise; without that discipline, aging studies risk becoming long, expensive and difficult to interpret [1].

“As a group we recognize that the complexity and diversity of Parkinson’s models, combined with the lengthy nature of aging studies, present challenges that require substantial resources and innovative approaches,” Andersen said. “Our work is aimed at making it easier for researchers to include aging as a critical element of their efforts to tackle this disease.”

Geroscience meets neurology

Beyond Parkinson’s, the paper signals a deeper convergence between geroscience and disease-specific research. Aging hallmarks – mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, altered proteostasis – are increasingly recognized as overlapping with early Parkinsonian pathology. By structuring experiments to interrogate those intersections directly, the consortium hopes to bridge fields that have often progressed in parallel.

Importantly, the authors do not present aging models as a panacea. They acknowledge practical constraints – time, cost, variability – and advocate for phased implementation [1]. The message is clear: if Parkinson’s is fundamentally age-associated, then aging must move from footnote to framework.

Time as a variable

Allowing models to age is not glamorous. It requires patience, resources and coordination across laboratories. But in a disease projected to rise in prevalence as populations age, time itself becomes an experimental variable that cannot be ignored.

The PD-AGE roadmap is, in essence, an invitation to recalibrate – to accept that biology unfolds on its own schedule and that translation may depend on our willingness to follow it. The question now is whether the field will.