Spatial multiomics promises to significantly deepen our understanding of biology by enabling the study of cells in their native environment. After all, cells do not act in isolation—they constantly “talk” to each other and interact with their surroundings through a complex network of molecular signals. Despite the transformative power of spatial multiomics, it has been less than a decade since the field came into its own, meaning numerous challenges lay ahead for the pioneers navigating uncharted waters.

Tamas Ordog, MD, professor of physiology and director of the Spatial Multiomics Core at the Mayo Clinic, believes spatial biology is “absolutely central” to medical research. Speaking to Inside Precision Medicine, he stressed how spatial omics allows scientists to directly interrogate patient samples in a way that was just not possible before.

Professor and Director

Mayo Clinic

Before spatial techniques first emerged, researchers had to rely on bulk analyses, which would yield an overview of gene or protein expression in the whole sample. With the arrival of single-cell methods, it became possible to narrow down these results, but these techniques still cannot provide detailed information about the tissue architecture or interactions between cells.

“Spatial biology allows us to answer two critical questions at the same time: Which cells are in your sample, and what are they doing?” said Ordog. Finding an answer to these questions can yield invaluable insights into the mechanisms of human disease and unlock new targets for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

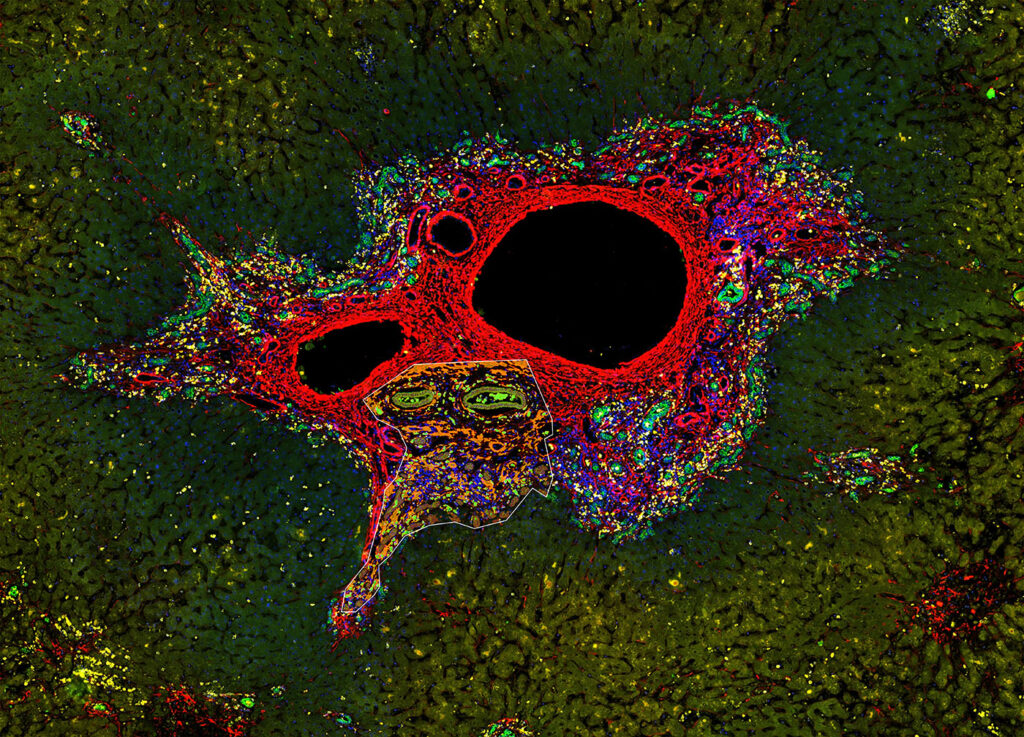

Although the field is still taking early steps, Ordog has seen exponential growth in spatial multiomics, with no signs of slowing down anytime soon. At the Spatial Multiomics Core, the majority of requests received focus on oncology, where uncovering interactions between the tumor and immune cells is essential to understand the underlying biology. “Typically, investigators come to us with a defined research question, and we find the best tools that are currently available to find the answer,” he said.

His team is tasked with guiding investigators through every step of the process, from identifying the right tools and performing the wet lab work to connecting users with a specialized computational team experienced in handling the large amounts of data generated by spatial multiomics techniques. In a constantly shifting environment, he emphasized that successfully navigating the maze of scientific and logistic challenges facing this field “literally takes a village.”

The ultimate goal is to bring spatial multiomics to the clinic. The core is actively developing omics technologies that go beyond initial discoveries, expanding into monitoring the course of disease and patient responses to medical interventions. For instance, ongoing programs are tracking the effects of RNA and CRISPR-based therapeutics on their cellular targets within a spatial context, but a lot more work remains to be done until the first clinical applications of spatial multiomics can reach patients.

A new horizon of possibilities

Jürgen C. Becker, MD, PhD, is a professor of translational oncology at the University of Duisburg-Essen and heads the division of translational skin cancer research at University Medicine Essen, which is part of the German Cancer Consortium. With a focus on skin cancer, his research group has worked extensively with single-cell transcriptomics.

“Before, we always had to infer cell-cell interactions by looking at their gene expression,” said Becker. “That’s why we were really excited when the first technologies for spatial transcriptomics came out on the market.”

Spatial omics can be groundbreaking for cancer research, where the tumor microenvironment and interactions with the immune cells surrounding or infiltrating the tumor are known to play a key role in disease progression. In a recent study, Becker and colleagues used high-resolution spatial transcriptomics to uncover how spatial context can influence gene expression and tumor cell plasticity in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), a rare but aggressive form of skin cancer. This led them to identify potential prognostic markers of tumor behavior and therapeutic targets to prevent resistance.

Professor

University of Duisburg-Essen

“What we saw was that if MCC cells are surrounded by normal keratinocytes, they also become more ‘normal,’ even if they keep the same genetic background,” Becker explained. Notably, he adds, these findings would have been nearly impossible to achieve before spatial techniques became available.

Since Becker and his team first started using spatial transcriptomics in their research work, just about four years ago, there have been significant technological advances in terms of the throughput, resolution, and coverage provided by commercially available equipment and tools. Now, the researchers are combining spatial proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics through collaborations with other groups.

As the field evolves, so do the regulations around it. Becker highlights how, since EU authorities introduced the category of low-intervention clinical trials in 2022, many groups have been able to more easily get approval for clinical trials that pose minimal additional risk or burden to participants. This has enabled researchers to carry out spatial biology experiments using real patient samples with less stringent requirements and simplified intake and monitoring procedures.

However, pricing remains a significant barrier of entry for many. A major limitation concerns the computational analysis of the massive amounts of data produced, which poses a substantial challenge to every research group venturing into spatial multiomics. “In the long run, we need to develop ways for computational solutions to really dive into interpreting the data,” said Becker.

Overcoming past limitations

Last year, spatial proteomics was chosen as the method of the year by Nature. But back in 2017, when Francesca M. Bosisio, MD, PhD, first published a method for multiplexed immunochemistry called multiple iterative labeling by antibody neodeposition (MILAN), she recalls often being met with a lack of understanding of the relevance of spatial biology.

“The term spatial biology did not even exist back then, and there were no commercially available methods,” said Bosisio, who is now a dermatopathologist and associate professor at the KU Leuven. She also directs the spatial proteomics unit at the Leuven Institute for Single Cell Omics, where the MILAN method is part of the spatial biology services offered.

Dermatopathologist

and Associate Professor

KU Leuven

“The pathology I was trained in was based on a lot of assumptions,” she said. “With multiplex chemistry, you could have certainty.” As a young pathologist in training, Bosisio had seen firsthand the limitations of having to detect each biomarker in a separate tissue section. This meant that in some complex cases where multiple markers were needed for diagnosis, the biopsy sample could be exhausted before pathologists reached a definitive diagnosis.

Since then, the popularity of spatial multiomics has exploded, not just in terms of the variety of technologies available, but with an increase in multiplexing complexity. More and more targets are now being detected and multiple omics can be combined on the same slide.

Although the number of institutions using and offering spatial multiomics services keeps increasing, many are just starting to dip their toes into the field. At the moment, only a few pioneering centers can provide end-to-end services, starting with the method selection. “All these technologies have different pros and cons,” said Bosisio. “There is not ‘the best’ technology, but the right technology for a research question.”

For instance, some techniques might have higher resolution but be limited to a region of interest, while others will cover the whole slide. Some might be cheaper because they rely on commercially available antibody probes, while others might be more expensive due the need for engineered probes. “There is always a trade off,” said Bosisio. “It is always about what you want to achieve for your specific project.”

Another obstacle for early adopters is the lack of standardization across the spatial biology field. As chair of the pathology working group at the European Society for Spatial Biology (ESSB), Bosisio is actively bringing more standardization across the field, from wet lab protocols and validated antibody catalogues to data analysis and quality control.

One of the most pressing issues on this front concerns sample preparation. Often, each institution will use their own protocols, each with different fixatives and incubation times. When introducing multiomics, the challenge gets compounded as it becomes necessary to ensure the consistent preservation of multiple types of molecular targets, such as RNA, proteins, lipids, or metabolites.

Downstream, Bosisio is tackling data analysis with the development of computational tools that users can apply to their experimental data without the need for a dedicated bioinformatics team. “The challenge that remains is to establish standardized guidance for the quality control and clean up steps needed before even starting the data analysis, to extract the right information from the sample,” said Bosisio.

With standardization, she ultimately hopes to democratize access to spatial biology. To this end, the ESSB is spearheading the creation of an international training network that seeks to move away from traditional compartmentalized education and instead focus on building multidisciplinary profiles that unite knowledge in the three key areas of pathology, spatial biology, and computational science.

A computational challenge

Kaibo Liu, PhD, Grainger STAR professor in the department of industrial and systems engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, had no prior background in biology when he first encountered spatial multiomics at a meeting he describes as driven by fate.

Professor

University of Wisconsin-Madison

A cancer diagnosis in 2021 led his son to get treatment at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. During one of the hospital visits, Liu got to know Jiyang Yu, PhD, chair of the department of computational biology at St. Jude, and decided to give back through a research collaboration. Their joint work resulted in the creation of Spotiphy, a computational tool that uses generative artificial intelligence (AI) to determine the proportion of different cell types at each location within the sample and then determine the gene expression of each cell.While other techniques can only take measurements at specific spots on the sample, leaving blanks in the data, Spotiphy leverages large amounts of spatial transcriptomics data and pathology imaging to fill in the gaps and provide a complete readout of gene expression throughout the whole sample.

“Our model is the first one that can be applied in the entire tissue,” said Liu. The algorithm was also shown to be much faster than other analytical tools currently available to researchers, which can significantly speed up research when dealing with the large datasets produced by spatial techniques.

It was the unique combination of Liu’s background in big data analytics and the spatial biology expertise of Yu’s research group that made this project possible. “It turned out tools I previously developed for engineering systems with industrial applications could be adapted to solve computational problems in spatial transcriptomics,” said Liu.

Still, the collaboration highlighted how high the entry barrier can be for those without specialized training. “This is one of the most challenging projects I have worked on since I joined faculty,” said Liu. Out of the two years it took from starting the project to publishing their results, he estimates the first year was mainly focused on getting his group to understand the terminology and acquire all the background knowledge necessary to identify and tackle the challenges facing the spatial multiomics field.

Going forward, the team plans to continue improving Spotiphy to integrate multiple modalities, improve reproducibility, and streamline the data acquisition and analysis steps. Liu’s son is now in remission and going back to St. Jude for regular checkups, giving him a chance to catch up with his collaborators.

Shaping the future of spatial multiomics

Despite making massive leaps in a short period of time, the field of spatial multiomics still faces many obstacles, but these can open the door to innovation. Across the board, experts agree that AI will play an important role in the development of spatial multiomics, especially as techniques evolve and the amount of data keeps scaling up.

“Using computational tools to integrate spatial multiomics data with clinical information will be central to how we can relay our findings to patient care,” said Ordog. “AI is the way to go. Foundation models can be trained to take diverse pieces of information and make predictions, enabling large-scale interrogation of patient samples.”

The computational challenge will only continue to grow as technology expands into new frontiers. The next decade will see the expansion of spatial techniques from thin, two-dimensional sections to larger, three-dimensional blocks of tissue, which will make the size of datasets grow exponentially.

Simultaneously, the integration of spatial multiomics techniques will gain adoption as the technology becomes increasingly accessible to researchers. While proteomics and transcriptomics have stayed in the limelight, Becker is looking forward to the integration of lesser known modalities such as genomics and epigenomics. In cancer research, these omics could provide unique insights into the clonal evolution of tumors or the regulatory pathways governing disease progression and immune response.

For his part, Ordog highlights the potential in going beyond just the “omics” and expanding into pathomics, an emerging field leveraging AI for the analysis of digital pathology images. Bosisio also remarked on the promise of honing in on cell–cell interactions by studying the interactome, which directly measures interactions between proteins. Her team is already integrating interactomics with spatial multiomics experiments to confirm which interactions cause the changes seen in the tissue.

Ultimately, the goal is to reach patients. FDA approval of the first spatial biomarker will be the next major milestone for the field, kickstarting the next generation of diagnostic and prognostic tests. “We are currently setting up the first IVDR (In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation)-certified workflow for spatial biology in our hospital,” said Bosisio. “We are also running a pilot study to identify the main indications for which spatial diagnostic panels could represent a significant advantage for the patient.”

To successfully introduce spatial biology in the clinic, it will be vital to shorten protocols to match the turnaround times required in a healthcare setting. Significant advances in commercial equipment, especially when it comes to throughput, will be needed to expand access. In the short term, certified diagnostic tests will have to be outsourced to reference centers, but Bosisio expects costs to go down over time as the number of providers increases and spatial biology is progressively implemented in every hospital and research center: “The more spatial biology becomes part of routine clinical work, the more precision medicine will become the standard.”

Clara Rodríguez Fernández is a science journalist specializing in biotechnology, medicine, deeptech, and startup innovation. She previously worked as a reporter at Sifted and editor at Labiotech, and she holds an MRes degree in bioengineering from Imperial College London.