Researchers in India have discovered a strategy that some pathogenic bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, use to attack immune cells before they even come into contact. Their findings show that these bacteria send out extracellular vesicles containing specialized lipids that stiffen the membranes of phagocytic cells, blocking key immune functions and allowing the invaders to evade immunity.

This research will be presented this weekend at the 70th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting in San Francisco.

Tuberculosis remains a major threat to public health, causing over a million deaths every year. M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes this deadly infection, is known to hijack the immune cells responsible for fighting infections off, but how exactly this happens remained unknown until now.

“Tuberculosis is rampant in India,” said Ayush Panda, former graduate student at the National Institute of Science Education and Research in Bhubaneswar, India. “I grew up in a state where tuberculosis outbreaks are a major problem, and I was always curious about how these diseases spread. That’s what drew me to this research.”

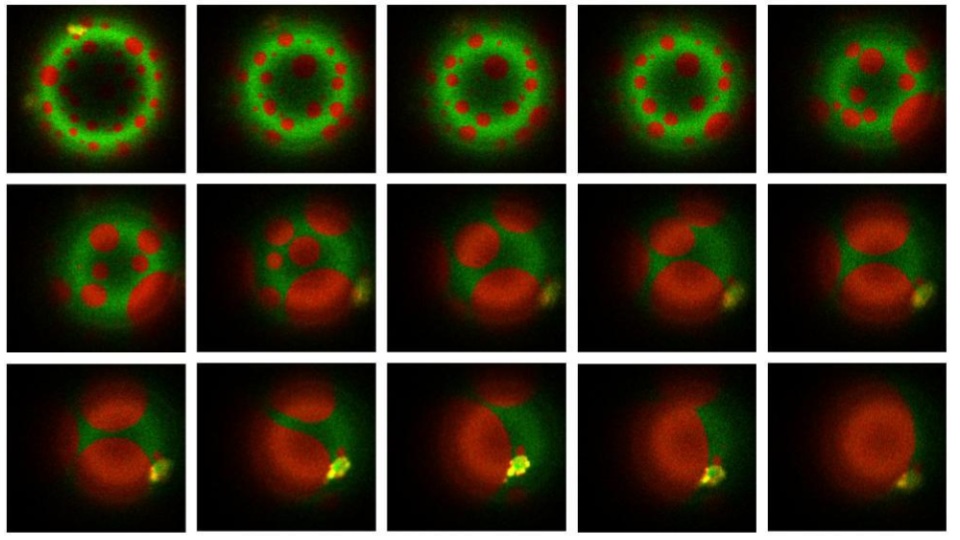

Panda and colleagues discovered that extracellular vesicles released by these bacteria contain lipid molecules that dramatically increase the tension of host cell membranes these vesicles fuse with. This phenomenon was found to disrupt normal functioning of phagosomes—vesicles that immune cells form around pathogens to trap them, later fusing with lysosomes containing digestive enzymes to dispose of the target.

“If the membrane becomes more rigid, it becomes much harder for the phagosome to fuse with the lysosome,” said Panda. “It’s an elegant biophysical mechanism: the bacteria remodel the membrane architecture to escape the very process that would have killed them.”

In addition, stiff membranes delayed the activation of signaling pathways involved in the maturation of phagosomes and their fusion with lysosomes. Even in those phagosomes that managed to fuse with lysosomes, the membrane tension stayed high, preventing them from fulfilling their role in killing the pathogens.

The bacterial vesicles did not just affect infected cells, but also nearby cells that still have not come into contact with the pathogen, weakening them in advance. Further experiments showed that the purified lipids alone were enough to stiffen host cell membranes and dampen the overall immune response.

“The most surprising finding was when we introduced mycobacterial lipids into membranes that mimic the host phagosome, we saw remarkable physical changes—the membrane properties were completely altered,” said Panda.

Importantly, the study found that this mechanism is not unique to tuberculosis infections. Extracellular vesicles of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus were also found to alter the tension of cellular membranes and delay phagosome maturation, suggesting that this could be an evolutionarily conserved survival strategy that several pathogens use to hijack human cells remotely through physical means rather than chemical.

“Now that we understand how the bacteria protect themselves, we can start looking for ways to stop them,” said Panda. “If we can block the bacteria from stiffening those membranes, our immune cells might be able to do their job and stop the infection.”