A study published today in Nature reveals a unique weakness of metastatic melanoma cells that have spread to the lymph nodes. These cells were found to rely on the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) to survive, opening the door for new therapeutic strategies against treatment-resistant and metastatic melanoma.

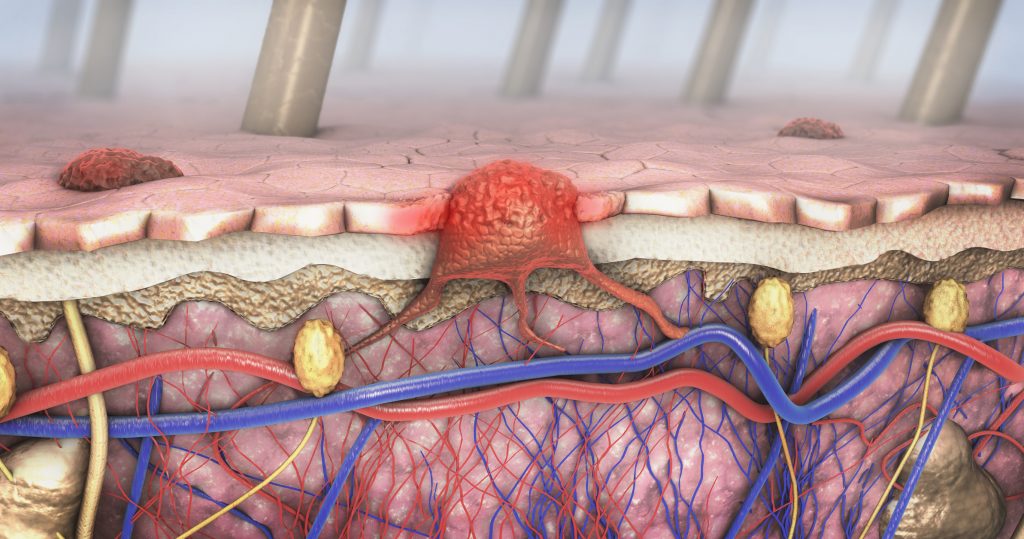

Ferroptosis is a form of cell death caused by the accumulation of oxidized lipids on the cell membrane, eventually leading to its rupture. The study found that metastatic cells can adopt different strategies to protect themselves against ferroptosis depending on the location they are spreading to. In particular, metastatic cells traveling to the lymph nodes were found to become reliant on FSP1 to keep ferroptosis at bay, and inhibiting this protein significantly reduced tumor growth in a mouse model of melanoma.

“Our study shows that melanoma cells in lymph nodes become dependent on FSP1 to survive, and that it is possible to decrease melanoma cell survival in lymph nodes with novel FSP1 inhibitors,” said Jessalyn Ubellacker, MD, PhD, assistant professor of molecular metabolism at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “These findings lay the foundation for potential new therapeutic strategies aimed at slowing cancer progression by targeting ferroptosis defense mechanisms.”

Cancer cells that become treatment-resistant or metastatic have previously been reported to rely on glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a protein that suppresses ferroptosis. However, while melanoma cells that metastasize to the blood depend on GPX4 to survive, those that metastasize to the lymph nodes stop relying on this protein while remaining protected against ferroptosis.

Using a mouse model of melanoma, Ubellacker and colleagues studied how the lymph node environment affects the strategies metastatic cells use to protect themselves. They found that while expression of GPX4 was reduced in these cells, levels of FSP1 were significantly increased. Treating these mice with selective inhibitors of FSP1 suppressed melanoma growth in the lymph nodes but not in primary tumors, showcasing a unique vulnerability of metastatic cells that spread to the lymph nodes.

“Metastatic disease, not the primary tumor, is what kills most cancer patients. Yet little is understood about how cancer cells adapt to survive in organs such as lymph nodes,” said Mario Palma, PhD, postdoctoral research fellow in the Ubellacker Lab and first author of the study. “We discovered that niche features of the lymph node actively shape which antioxidant systems melanoma can use. That context-specific dependency had not yet been fully appreciated and suggests that, rather than trying to kill every tumor cell the same way, we can exploit the weaknesses that arise as cancer spreads.”

In addition to revealing FSP1 as a promising new target against metastatic melanoma, these findings highlight the importance of studying complex processes like ferroptosis within their tissue context. Given the potential of ferroptosis as a target not just for cancer, but also for neurodegenerative and ischemic disease, further work to characterize tissue-specific changes could be instrumental for the development of a new generation of targeted therapies.