On a foggy morning in the town of Asilomar in California, neuroscience and bioethics experts assembled this week to seek clarity, both visual and beyond. The primary question that they wanted to answer: What are the ethical considerations and societal implications of human neural organoids research?

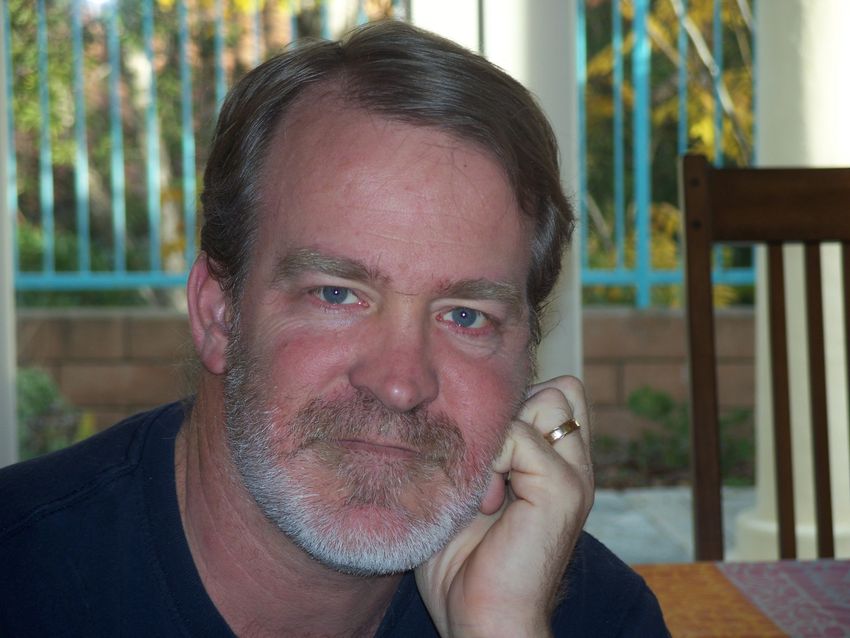

Hank Greely, a bioethicist at Stanford University, helped organize a meeting on the ethical and societal implications of neural organoids and assembloids.

Hank Greely.

Human neural organoids are 3D assemblies of neurons generated from stem cells. Fusing one of more types of organoids creates an assembloid. Over the past few years, research on brain organoids and assembloids has made great strides: In 2022, Sergiu Pasca, a Stanford University neuroscientist, successfully integrated and stimulated human neurons in rat brains; earlier this year, Pasca’s team generated a four-component assembloid that mimicked the sensory circuit of a pain pathway.1,2

“If [neural organoids] were human, we’ve got Institutional Review Boards; if they were animals, we’ve got the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee—but they’re neither,” Henry (Hank) Greely, a bioethicist at Stanford University told The Scientist in a recent interview. “There’s no regulatory setup that’s looking at the organoids as organoids.”

Rapid progress in this field has prompted previous discussions regarding the need for regulations in human neural organoids research. To continue these conversations, Pasca and Greely organized the “Ethical and Societal Implications of Neural Organoids, Assembloids, and Their Transplantation” meeting in November 2025 for open debates and brainstorming sessions among experts. In a spirited discussion at one of the sessions, panelists and attendees got into the weeds of ethical conundrums, societal acceptance, and inclusion barriers in the field.

Neural Organoids Governance: Is Broad Consent from Donors the Right Approach?

The process for creating neural organoids often involves using stem cells from donors as the starting material. A common practice in the field is getting broad consent from donors, meaning that while donors may be donating their cells for a specific study at the time, they often sign off usage of their cells for potential future studies.

Nita Farahany, a law and ethics expert at Duke University, discussed the issues with obtaining broad consent from donors in organoid research.

Courtesy: Nita Farahany

However, this approach has shortcomings. Human neural organoids live long in cultures—1,000 days (maybe longer)—so it is hard to anticipate all the different ways in which they could be used over time. For instance, cells used for creating disease-specific organoids could be used for studying a different disease or an academic project might find commercial applications–changes that cell donors might not be comfortable with.

“Progress in the field of neural organoids underscores the promise and urgency of getting governance right,” said Nita Farahany, an expert on legal and ethical implications of emerging technologies at Duke University.

Rather than asking donors to sign off on blanket projects that they cannot envision, Farahany believes, “We need mechanisms of continual governance rather than broad consent.”

According to her, in addition to informed consent, setting up advisory panels that could consist of disease advocacy groups and patient families for the governance of human neural organoids could be an effective path forward.

Ensure Inclusion: Do Vulnerable Groups Have a Voice?

One of the exciting applications of human neural organoids research is creating disease models to study neurological disorders. Organoid models of autism would be extremely helpful in helping people understand the genesis of the condition during development. “It is an extremely promising area of inquiry,” said Alison Singer, president and cofounder of the Autism Science Foundation.

Alison Singer, cofounder of the Autism Science Foundation and parent and guardian to two autistic adults, spoke about the need for better inclusion of vulnerable groups in decisions concerning neurological studies.

A. Fell, Worldview Studio

However, the work on organoid disease models, just like other autism studies, faces an uphill battle as some neurodivergent groups oppose autism spectrum disorder causation studies and push for social studies instead, according to Singer. “Focus on the social model of autism has come at the expense of research looking at the medical model and causation,” said Singer, citing the shutdown of the UK’s Spectrum 10k project (they intended to collect DNA from 10,000 patients to understand heritability and comorbidities) by such groups as one example.

Singer also noted that with the autism spectrum definition becoming so broad that it’s gotten “meaningless,” the more vocal groups can influence research directions easily, while patients with profound autism—defined as having an IQ below 50, limited or no verbal abilities, and a dependence on caregivers—are largely excluded in decision making.3 This is because although 27 percent of people with autism have profound autism, they cannot speak for themselves, and parents or caregivers are not currently seen as stakeholders as they do not have lived experience. This has created a major inclusion gap where the most vulnerable group has no voice.

Singer, who is a parent and guardian to two autistic adults, and other advocacy groups are working to change this scenario to ensure more inclusivity in neurological disease studies, organoids and beyond.

Address Public Concerns: Do Neural Organoids Experience Consciousness or Pain?

The brain is rather complex, and interplay between different regions and circuits is essential for its proper functioning. Although it is made up of different components, the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts. However, as neuroscientists see success with multi-component assembloids, concerns about organoids being “mini brains” in a dish and questions about them being conscious are bound to arise from people outside of research.

Although all panelists unanimously agreed that organoids are not conscious—based on scientific definitions of consciousness involving memory creation and retention—they did discuss simple tests that scientists could perform as ongoing checks to alleviate any public concerns.

John Evans, a social scientist at UCSD, spoke about how scientists can address public concerns about their work through education and meaningful engagement.

Courtesy: John Evans

According to John Evans, a social sciences expert at the University of California, San Diego who has surveyed public opinion on this topic a few years ago, the public worries stem from sentimental associations with donors cells.4 “People associate emotions with them because many think organoids and human tissues retain connections to the individuals,” said Evans.

This means that they might worry about organoids feeling pain or sharing thoughts of the donor individual. Although researchers know that this is not the case–Pasca clarified that their assembloids had the pain sensing circuit but lack the region that registers the aversive response of “feeling pain”—a few attendees voiced that it was up to the scientists to educate people to address their concerns. Evans added that when doing so, scientists must solicit public opinions without trying to influence their thoughts with strategic nomenclature or questions.

“We do not want to know if the public agrees with the framing of our thoughts; we want to know what their concerns are without us prompting specifics,” said Evans.

While there is still work to be done on solving these issues and even as experts respectfully disagree regarding the specifics, they have a common goal: making human neural organoid research safe and acceptable in society. Alignment on definitions for accurate scientific outreach from media and scientists is the first step in this long journey, attendees agreed, as the fog cleared.