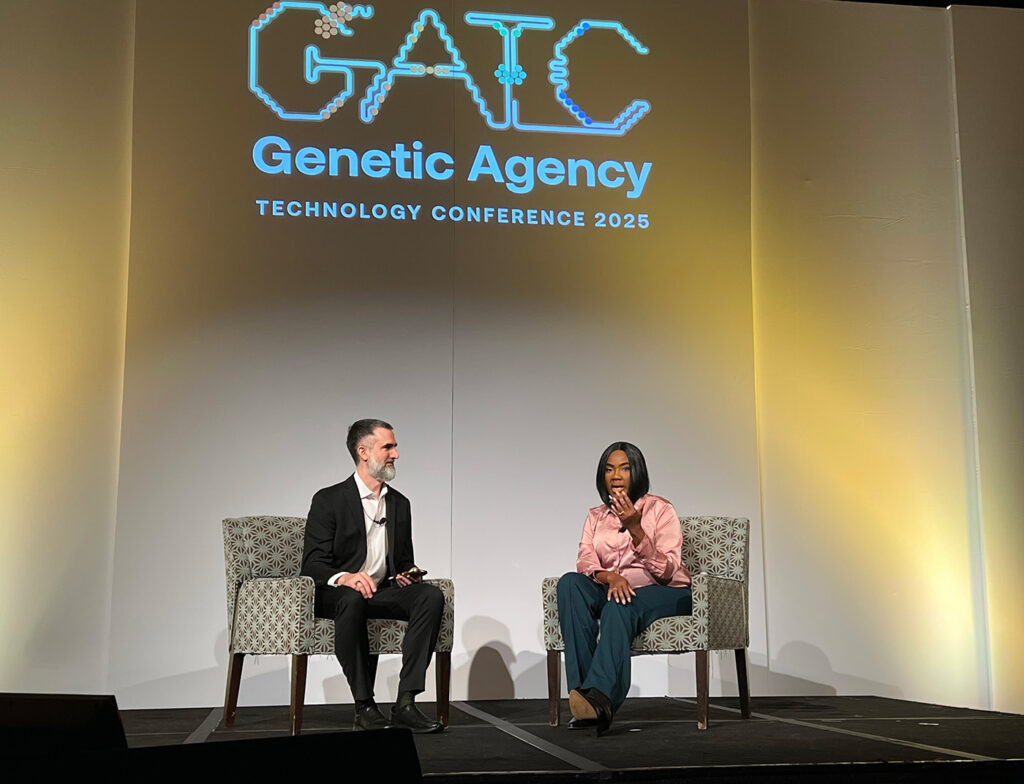

BOSTON – Dyno Therapeutics hosted an ambitious event in Boston this week, the Genome Agency Technology Conference (GATC)*, striving to bring together a broad coalition of researchers and executives in cell and gene therapy, gene editing, drug discovery and AI as well as patients and advocates to forge new pathways of collaboration to expedite progress in delivering therapies to patients.

The one-day conference was the brainchild of Eric Kelsic, PhD, the founding CEO of Dyno, a biotech company co-founded by Harvard Medical School geneticist George Church, PhD, in 2018. Kelsic said the idea for GATC was hatched earlier this year, shortly before the American Society of Cell and Gene Therapy meeting and steadily expanded in scope.

The meeting hinges on the concept of genetic agency, which Kelsic defined as: An individual’s ability to take action at the genetic level to live a healthier life.

The concept was fleshed out in a diagram shown by Kelsic that highlighted half-a-dozen key factors, including hope, delivery, genetic insights, the patient, investment, and doctors, all underpinned by advances in technology.

While Kelsic did slip in a few new Dyno announcements into the main program, including an improved AAV capsid to target muscle, updates to the company’s AI agent platform, and a manufacturing partnership expansion, GATC succeeded in maintaining a mission-driven, rather than promotional, atmosphere.

Two programming features helped immensely in this regard. One was the presence of a professional moderator, Misha Glouberman, who effectively asked the audience to seek out people they did not know and strike up conversations early in the day. The result was a buzz of conversation and an enthusiastic embrace of new allies and shared purpose.

More importantly was the presence of three remarkable women on the program, each sharing their inspirational story as a patient or a patient advocate.

Sonia Vallabh, PhD, shared her journey as a non-scientist confronting the diagnosis of a rare prion disease and taking action to devise a therapy to tackle her own disorder. Together with her husband, Vallabh trained as a scientist, and together they run a group of 17 staff at the Broad.

Progress is being made, but not quickly enough. “At this point, I’ve cured thousands of mice,” Vallabh joked.

Working on a divalent siRNA approach, Vallabh hopes to treat the first patient in early 2026. In conjunction with the group of Jonathan Weissman, PhD, at the neighboring Whitehead Institute, Vallabh is also pursuing an epigenetic editor to methylate the PRP promoter. This program could enter the clinic in 2027, contingent on ongoing discussions with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

How those conversations go is hard to predict. Vallabh pointed to differing guidelines offered by CDER and CBER. “We’re up against human judgement calls and that’s scary,” she said. “It’s harder for me to accept if human systems are the reason we can’t get this done.”

Vallabh sees the major challenges that lie ahead. “I could imagine being responsible for, or being, a gene therapy death. This is messy,” she said.

The Victoria line

Special guest at GATC was Victoria Gray, the trail-blazing patient with sickle cell disease (SCD) who in 2019 became the first SCD patient to undergo CRISPR therapy in the Vertex/CRISPR Therapeutics exa-cel trial.

Embracing her role as a public speaker, Gray spoke for 15 minutes without notes, her life story tumbling out. After her worst pain crisis in 2010, she “gave up on any and all dreams,” just hoping to be “a good mom and a good wife.” Seeking medical care in her home state of Mississippi, Gray said she felt unseen. “Women would get called back [in the ER] for pink eye before me,” she said.

Her life changed in 2018, traveling 5.5 hours to Nashville, Tennessee, to meet bone marrow transplant specialist Haydar Frangoul, MD. “I wish I would’ve met you 10 years ago,” Frangoul told her. “He was the only doctor in my adult life to join the fight for me,” Gray said.

As a patient, Gray emphasized, “we’re more than just a patient—we’re people.”

Chemotherapy was the scariest part of the procedure, Gray recalled. “The known was scarier than the unknown.” Today, Victoria is 6.5 years asymptomatic. “Life is completely different. I travel the world!” She recently joined a group hike with fellow patients, advocates and physicians in Colorado, reaching 12,500 feet to raise funds for charity.

Asked by Kelsic about her motivation going forward, Gray said “My motivation is to bring hope to other patients… Genetic Agency would feel like patients have options.”

New York minute

Allyson Berent, PhD, is the chief science officer of the Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics (FAST). She is also the parent of a child, Quincy, with a rare genetic disorder.

Following her daughter’s diagnosis, Berent was told by a doctor: “I have catastrophic news for you.” In shock, Berent simply replied: “How do you spell Angelman syndrome?”

Berent, who trained to be a vet, committed to finding a cure for her daughter. “I hate neurology, I hate genetics. This did not bode well for me,” she quipped. But it did not stop her.

Angelman syndrome (AS) is a neurological disease caused by the deletion of one copy of the UBE3A gene. The other copy is silenced due to genetic imprinting, raising hope that restoring expression of the other allele offers a viable path to treatment.

“There is only one cell to target—it just happens to be the hardest, the neuron,” she said. AS patients cannot speak and only sleep for a few hours a night, imposing additional strain on parents and family members.

“This is a great decade to be a mouse with AS,” she said, echoing a point Vallabh had made. Thankfully, that groundwork in animal models and a fierce determination to raise millions of dollars for research has led to tangible progress in the clinic.

FAST raised $5.8M raised in six weeks to test half-a-dozen platforms from bench to candidate, including gene replacement (via AAV delivery), and un-silencing the genetic imprinting using allele-specific oligonucleotides or CRISPR.

In 2022, Ultragenyx Pharmaceuticals acquired GeneTx BioTherapeutics, developing an antisense oligo treatment. There are now six programs in the clinic. Two weeks ago, in a collaboration with MavriX Bio, a biotech company co-founded by James Wilson, MD, PhD, the first AS patient was dosed with an AAV gene therapy. “You have to be disruptive and shake it all up,” Berent said.

“The enemy of good is better…. Patients are waiting,” Berent said. “Drug development is hard, but living with rare disease is harder.” These new therapies “don’t belong in a bioreactor [or] a freezer… they belong in patients.”

Judging from the reactions of most of the attendees at the end of an absorbing day, GATC is at the very least a worthy addition to the conference calendar. Whether the rallying cry of genetic agency will catch fire remains to be seen.

*GATC 2025; Boston, November 11, 2025.