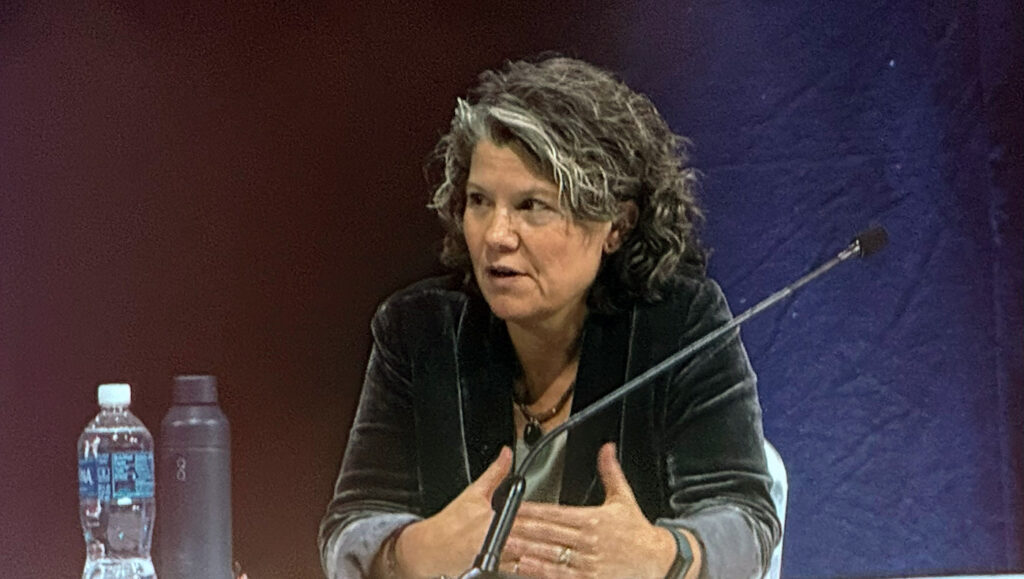

At AMP25 in Boston, Heidi Rehm, PhD, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Genomic Medicine Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, delivered a sweeping and candid talk on one of the most persistent problems in clinical genetics: the Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS).

“It’s both my favorite topic and my most dreaded topic,” she began, acknowledging the enormous clinical and logistical burden VUS results create for laboratories, clinicians, and patients.

The scale of the VUS problem

Rehm opened by revisiting one of her group’s landmark studies examining 1.5 million genetic tests across 19 laboratories in the United States and Canada. The findings were stark: 33% of all tests returned at least one VUS.

“That is one-third of all genetic tests coming back with uncertainty,” she emphasized. “It’s a huge burden—clinically, emotionally, and operationally.”

The problem scales with gene-panel size: the more genes added, the more VUS results return. And while clinicians often debate whether VUS results should be returned at all, the audience poll at the session revealed divided views: many wanted VUS returned in all contexts, but the majority favored returning them only in symptomatic cases, aligning with current clinical practice.

Why return VUS at all? The benefits and risks

Rehm laid out the core arguments for returning VUS:

- They allow immediate evidence generation, including parental and segregation testing.

- They motivate deeper phenotyping.

- They enable research investigations and functional studies.

- They allow patients and clinicians to track evolving interpretations over time.

But she also highlighted the risks:

- “Returning a VUS can absolutely introduce anxiety,” she noted.

- They strain healthcare systems when clinicians chase uncertain findings.

- They can lead to clinical mismanagement when misinterpreted.

- They may even deter clinicians from ordering genetic tests.

“This is the dilemma,” Rehm said. “If we eliminated VUS entirely, we’d avoid the burden—but we would also lose the opportunity to resolve them.”

Updating classification standards: The coming shift to SPCV4

Much of Rehm’s talk focused on efforts to modernize variant classification guidelines. The current ACMG/AMP framework (2015) is being overhauled into what she called SPCV4, now in pilot testing across 30 laboratories.

The revisions include:

- A Bayesian, points-based system

- Clearer rules to avoid double-counting evidence

- Introduction of VUS subclasses (low, mid, high)

Rehm stressed that subclassification is crucial: “Our data show that VUS-low almost never moves to pathogenic. In contrast, VUS-high is the bucket most likely to be reclassified, and almost half of those ultimately become pathogenic. That distinction matters.”

Audience polling confirmed strong agreement that less evidence should be required to call a variant likely benign, a direction SPCV4 is taking.

In one pilot example, nearly half of all VUS reclassified to likely benign when SPCV4 criteria were applied, an enormous potential reduction in clinical noise.

Improved predictors and functional assays

Rehm highlighted advances in computational prediction tools, such as REVEL, AlphaMissense, and burgeoning efforts in indel prediction and regulatory variant modeling. Modern algorithms, she explained, now achieve evidence levels strong enough to meaningfully impact variant classification.

“We’ve come a long way from the days of SIFT and PolyPhen,” she said. “But we must be careful not to double-count overlapping types of evidence.”

She also spotlighted large-scale functional efforts such as the MAVE (Multiplex Assays of Variant Effect) Consortium, now housing over nine million variant measurements, with standardized methods for mapping experimental data to clinical classification levels.

“These assays are becoming essential tools,” Rehm said. “But we need strong calibration to ensure they are used appropriately.”

Global data sharing: The path forward

Rehm argued that data sharing is the single most powerful tool for resolving VUS. Yet massive global inequities remain: population databases are still dominated by people of European ancestry.

“When we added half a million European genomes to gnomAD, we barely gained any new common variants,” she explained. “But adding non-European genomes yielded a substantial increase. That tells us exactly where the gaps are.”

Projects such as Federated gnomAD, the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH), and ClinVar curation initiatives are helping to correct these gaps. Rehm’s team alone has reviewed nearly 25,000 ClinVar records, resolving thousands of conflicts.

She emphasized the importance of variant-level matchmaking platforms—including VariantMatcher, GeneMatcher, and NHGRI’s AnVIL—which allow researchers to query global databases for matching cases and phenotypes.

“It’s incredibly powerful,” she said. “We’ve made gene discoveries this way, and increasingly we can use these networks to resolve clinical VUS as well.”

A call to action

Rehm closed with a message of collective responsibility: “We are all in this together. Reducing the VUS burden requires everyone—clinicians, labs, researchers, and global partners.”

Her recommendations:

- Share your data.

- Write informative genetic reports with VUS subclasses.

- Support segregation studies and clinical investigations.

- Join community efforts—ACMG/AMP committees, ClinGen expert panels, GA4GH initiatives.

“If we work together,” she concluded, “we can dramatically reduce uncertainty, improve patient care, and push the field toward a future where VUS is far less common and far less burdensome.”