Gender, native-language background, and national income level shape researchers’ perceived publication productivity.

From hiring decisions to grant awards, publication counts determine which scientists advance and whose work is seen as influential. Those metrics overwhelmingly rely on papers published in English, the dominant language of global science. But a recent study published in PLoS Biology challenges the idea that English-language output is a reliable measure of productivity.1

Surveying scientists across eight countries, researchers led by Tatsuya Amano, a conservation scientist at the University of Queensland, examined how gender, native-language background, and national income level shape scientific publishing as well as how those factors combined affect perceived productivity. The researchers found that women, non-native English speakers, and researchers in lower-income countries publish significantly fewer English-language papers, even when they produce substantial work in other languages. The result, the authors argued, is that English-centric metrics can mask productivity and amplify inequities in global science.

“It’s not just about how scientists are perceived—it directly affects our professional opportunities,” said Valeria Ramírez-Castañeda, a coauthor of the study and data scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. The consequences go far beyond visibility, she added. This perception can shape the entire trajectory of a scientist’s career.

Amano said that the project emerged from his work on language barriers in science.2 He had suspected those challenges often intersected with gender and economic disadvantage, but he noted that few studies had examined their combined effects. “The novelty of this paper lies in that we quantified what many people had already suspected,” he said. “I believe…providing quantitative evidence is a crucial first step towards solving any issue.”

To investigate these patterns, the researchers ran an online survey translated into multiple languages that reached 908 environmental scientists across eight countries. Participants reported how many papers they had published in English and in other languages, along with basic details such as their gender, career stage, and discipline. The team then compared publication totals across groups while accounting for how long each person had been doing research. They also tested how gender, language background, and a country’s income level combined to shape publication records. By analyzing English-only output and then repeating the analysis using researchers’ full publication lists, the authors showed how much productivity is hidden when only English-language papers are counted.

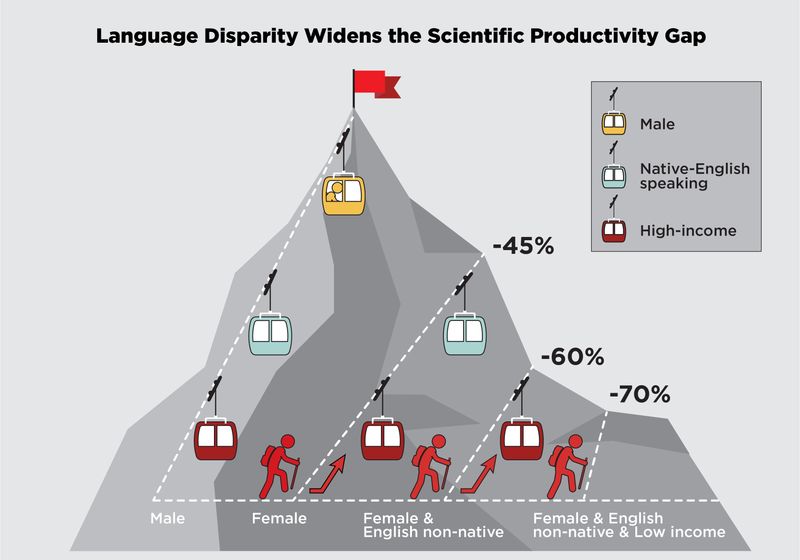

When analyzing the number of English-language papers different populations of researchers published, Amano and his team saw clear differences between male and female researchers. English publication output also differed for non-native English speakers and those from low-income countries. The height of the mountain represents the number of English-language papers published. The percentages in this graph indicate the percent fewer publications each group produced compared to English-native speaking male researchers from high-income countries.

Erin Lemieux, Tatsuya Amano, Amano T et al. 2025 PLoS Biology. CC-BY 4.0

The analysis revealed steep differences in English-language totals across groups. Early in their careers, women had published up to 45 percent fewer English-language papers than men with comparable research experience. That gap widened for non-native English speakers: Women in this group had produced roughly 60 percent fewer English-language papers than native-English-speaking men. The sharpest disparities appeared when gender, language background, and national income were combined. Women who were non-native English speakers working in lower-income countries had about 70 percent fewer English-language publications than men from high-income, English-speaking nations.

The authors noted that the results show associations, not proof of cause and effect. However, when they looked beyond English-language output, a sharply different pattern emerged, revealing that several groups who seemed less productive based on English-only counts had higher overall publication totals once non-English papers were included. This was especially true for non-native English speakers and researchers in lower-income countries, many of whom reported substantial work in other languages alongside their English publications.

While noting that the survey’s English-mediated distribution may have excluded researchers facing the steepest linguistic barriers, University of Wisconsin-Madison information scientist Chaoqun Ni praised the study’s rigorous statistical approach and open code availability.

What she found most sobering, however, was the gender pattern: Even when counting all papers in all languages, women still published less than men, suggesting barriers that may be independent of the language or economic factors measured in the study.

Amano and his team discussed points that help explain why certain researchers appear less productive under English-only metrics—the “dual burden” Ni said that non-native English speakers face. Earlier work showed that these researchers spend up to 51 percent more time writing a manuscript in English, experience rejection due to English writing up to 2.6 times more often, and are asked to improve their English during peer review as much as 12.5 times more often than native speakers.

For Ramírez-Castañeda, the findings reflect a pattern she sees across Latin America. “Because English-language journals receive more attention and visibility, this is often mistaken for being more important,” she said. As a result, work grounded in local priorities can count for less in hiring or promotion, and the pressure to publish in English pushes researchers toward collaborations with the Global North, which can end up shifting agendas.

Commenting on the economic dimension of the study, Moumita Koley, a science policy scholar at the Indian Institute of Science explained that institutions in developing countries like India vary widely in resources, and “we cannot expect the same outputs from well-funded and poorly funded institutions. There has to be a realistic calibration of expectations and appreciation for both categories.”

Koley said that any move to value non-English outputs must be context-specific. “There can’t be a one-size-fits-all solution,” she said, explaining that policies should follow only once practical strategies—including how they affect the evaluation of research productivity— are in place.