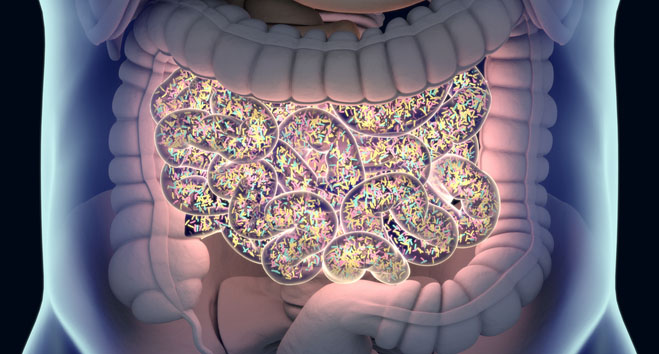

A study looking at the potential impact of common industrial and agricultural chemicals on the human gut microbiome showed around one in six chemicals slowed the growth of at least one microbe found in the gut.

Previous research shows this kind of effect on the gut microbiome could reduce the amount of beneficial bacteria in the gut that help us to digest our food and maintain good overall health and promote the growth of strains resistant to the chemicals and to antibiotics.

As reported in Nature Microbiology, the researchers tested 1076 chemicals that could enter human bodies through food, water, and environmental exposure. Around 80% of these chemicals are herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides and at least 15% were industrial chemicals such as bisphenol A, flame retardants, and forever chemicals like polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Most of these man-made chemicals have been assumed to only act on the specific targets they are designed to combat in the past. While some are known to be toxic if people are exposed to high levels, research on the potential impact of exposure on the gut microbiome is fairly limited.

The current study tested the impact of the panel of chemicals on 22 strains of bacteria commonly found in the human gut, the majority of which were strains normally referred to as beneficial microbes.

About one in six of the tested chemicals (168 in total) inhibited at least one strain of gut bacteria, and 588 significant chemical–bacteria inhibitory interactions were recorded in total.

The team notes that fungicides and industrial chemicals had the strongest impact on the panel of bacteria with around 30% of this group showing a potentially negative impact on the panel of gut bacteria.

“We’ve found that many chemicals designed to act only on one type of target, say insects or fungi, also affect gut bacteria,” said first author Indra Roux, PhD, a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit, in a press statement.

“We were surprised that some of these chemicals had such strong effects. For example, many industrial chemicals like flame retardants and plasticizers—that we are regularly in contact with—weren’t thought to affect living organisms at all, but they do.”

The bacteria most vulnerable to chemical exposure seemed to be members of the order Bacteroidales. These are among the most abundant and stable bacteria in the gut, breaking down complex dietary fibers and host-derived carbohydrates, as well as producing metabolites such as acetate and propionate that influence gut barrier and immune function.

This research was carried out in a lab setting, but the research team now wants to assess if they can find similar evidence of the impact on the gut microbiome from people known to be exposed to these chemicals.

“Now we’ve started discovering these interactions in a laboratory setting it’s important to start collecting more real-world chemical exposure data, to see if there are similar effects in our bodies,” said Kiran Patil, PhD, a professor at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit, and co-lead author of the study.

In the meantime, the research team is using the data they collected along with machine learning to try and predict the impact each of these chemicals could have on the gut microbiome.

“The real power of this large-scale study is that we now have the data to predict the effects of new chemicals, with the aim of moving to a future where new chemicals are safe by design,” said Patil.