A study published in Cell by researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital unveils a previously unknown form of cell death—mitoxyperilysis—that arises when innate immune activation converges with metabolic disruption. Beyond illuminating a fundamental biological process, the team demonstrated that this pathway can be exploited to shrink tumors in vivo, offering a new direction for cancer therapy.

The discovery emerged from the laboratory of Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, PhD, director of the St. Jude Center of Excellence for Innate Immunity and Inflammation. Her group has long studied how immune and metabolic stresses shape inflammatory cell death. Yet the synergistic combination of these processes is rarely examined—a gap the new study now fills.

“We discovered that innate immune and metabolic disruptions led to a synergistic effect activating a new cell death pathway that we characterized as mitoxyperilysis,” Kanneganti said. “Understanding cell death pathways is literally a matter of life and death. We believe that by mechanistically defining this new pathway, we’ve provided biochemical nodes that can be investigated for future lifesaving therapeutic interventions.”

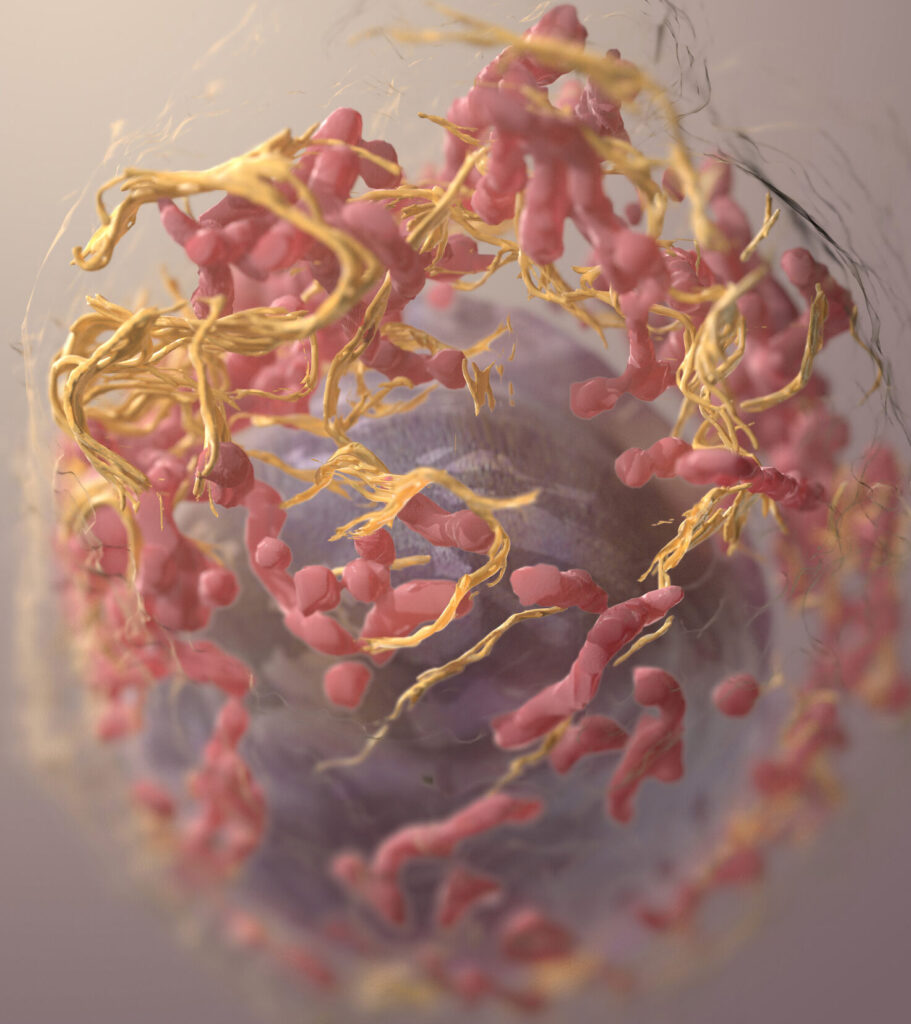

Mitochondria drive membrane rupture

The researchers found that when cells experience both nutrient limitation and innate immune stimulation, their mitochondria accumulate oxidative stress and migrate toward the cell’s plasma membrane. Instead of retracting, they remain locked in place, causing localized oxidative damage that ultimately ruptures the membrane. This catastrophic failure—distinct from pyroptosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis, PANoptosis, and other known pathways—is what the team terms mitoxyperilysis.

Probing its regulation, the scientists identified the metabolic kinase mTORC2 as a key modulator. Inhibiting mTOR restored cytoskeletal dynamics that normally move mitochondria away from the membrane, preventing lysis. The team also found that mitochondrial oxidative stress required the apoptotic signaling components BAX, BAK1, and BID, though the resulting death was caspase-independent.

Melanoma cells are highly sensitive

While the discovery itself is fundamental, the team also uncovered evidence that mitoxyperilysis could be harnessed to kill cancer cells—particularly melanoma.

Addressing questions about cancer specificity, Kanneganti explained:

“In our study, we specifically assessed the ability of mitoxyperilysis to be activated and regress tumors formed by melanoma cells, and we found that these cells were highly sensitive to this pathway. We did not directly test any other cancer types; however, since the receptors and molecules needed to activate this pathway are also present on other types of cancer cells, it is likely that this pathway could be activated in a wide variety of cancers.”

The sensitivity stems from cancer cells’ unusual metabolism. Their reliance on glycolysis and dysregulated tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity leaves them more vulnerable to metabolic stress than healthy cells.

“Our data suggest that cancer itself does not activate this pathway; instead, therapeutic intervention to induce metabolic disruption and innate immune activation in cancer cells can activate it,” Kanneganti said. “Cancer cells are inherently more susceptible to metabolic disruptions than other cell types, due to their dysregulation of the TCA cycle and increased dependence on glycolysis. In line with this, we observed that metabolic disruption alone was sufficient to induce lytic cell death in ~30% of B16 melanoma cells. In contrast, this could not induce lytic cell death in macrophages.”

However, metabolic disruption alone was not enough to shrink tumors in vivo. In vivo, though, metabolic disruption alone only resulted in a tumor-static effect, stopping the growth of a tumor but not reducing its size. “When we combined fasting with innate immune activation, this induced cell death (mitoxyperilysis) in >80% of B16 melanoma cells, which led to a tumoricidal effect, regressing the tumors in an in vivo model,” Kanneganti explained.

Therapeutic possibilities

The combination therapy tested in the study—fasting to disrupt metabolism and intratumoral LPS to activate innate immunity—rapidly reduced tumor size in mice, far outperforming either intervention alone.

“In our in vivo models, we found that combining metabolic disruption (through fasting) with innate immune activation (through intratumoral injection of lipopolysaccharide, or LPS) had a profound ability to regress tumors,” Kanneganti said. “This suggests that direct translation of this approach may be possible in patients.”

Previous clinical trials have already used fasting or innate immune activation (e.g., Coley’s toxin) individually for cancer treatment, but these have been met with mixed success. Says Kanneganti, “Our findings show that using a combinatorial approach will be superior and could be pursued for patients.”

A call for multidisciplinary science

For researchers working at the nexus of metabolism and innate immunity, the study offers more than a new pathway—it demonstrates the power of cross-disciplinary thinking.

“This study emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary approaches in science,” Kanneganti said. “Innate immunity is our first line of defense, constantly surveying for threats, and it is fundamentally interconnected with cell death, inflammation, and metabolism. This coordinated network shapes host responses; yet these processes have often been studied in silos. Focusing on only one aspect of the complex physiology that occurs during disease is an oversimplification and limits our ability to make physiologically relevant discoveries.”

“Here, by using a combinatorial and multidisciplinary approach to bring these fields together, we were able to identify a new pathway and characterize its molecular mechanisms and clinical translation.”