Researchers studied the genomic characteristics of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes to trace the history of eukaryotic cell origins.

Approximately four billion years ago, the first forms of life emerged on Earth. For eons, biological life consisted of prokaryotic organisms, either early bacteria or archaea. Determining when eukaryotic cells emerged has been challenging. Many hypotheses point to complex, eukaryotic life emerging around two billion years ago, coinciding with the introduction of the mitochondria into cells shortly after Earth’s atmosphere became more oxygen-rich.

However, a new study led by researchers at the University of Bristol suggests that the eukaryotic cell began taking shape almost one billion years earlier than previously thought. Tracking gene duplication events in a representative sample of organisms across the tree of life, the researchers showed that many key eukaryotic traits likely emerged before the capture of the organism that would become the cell’s mitochondria.1 These findings, published in Nature, offer key clues into the history of complex life on Earth.

To begin resolving when eukaryotic cells emerged, the team created a phylogenetic tree with multiple taxa of eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea by estimating their evolutionary rate using 62 genes. Using this tree like a molecular clock, they determined that the branch of archaea that would give rise to the nucleus (nuclear first eukaryotic common ancestor, nFECA) diverged between 3.05 and 2.79 billion years ago. Meanwhile, the team’s clock indicated that the bacteria that would become the mitochondria (mitochondrial first eukaryotic common ancestor, mFECA) branched from its relatives between 2.37 and 2.13 billion years ago.

Using these timeframes, the researchers looked in the genomes of their representative organisms in gene families that originated in prokaryotes for gene duplications; these events are characteristic of eukaryotes.2 The team identified more than 100 such families with duplications in genes with either archaeal or bacterial origins.

They saw that gene duplications originating from archaeal genes began prior to the estimated introduction of the mitochondria and their associated metabolic changes. Meanwhile, most of the bacterial gene family duplications did not emerge until after mitochondrial symbiosis occurred.

“One of our most significant findings was that the mitochondria arose significantly later than expected. The timing coincides with the first substantial rise in atmospheric oxygen,” said evolutionary biologist and study coauthor Philip Donoghue from the University of Bristol in a press release. “This insight ties evolutionary biology directly to Earth’s geochemical history. The archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes began evolving complex features roughly a billion years before oxygen became abundant, in oceans that were entirely anoxic.”

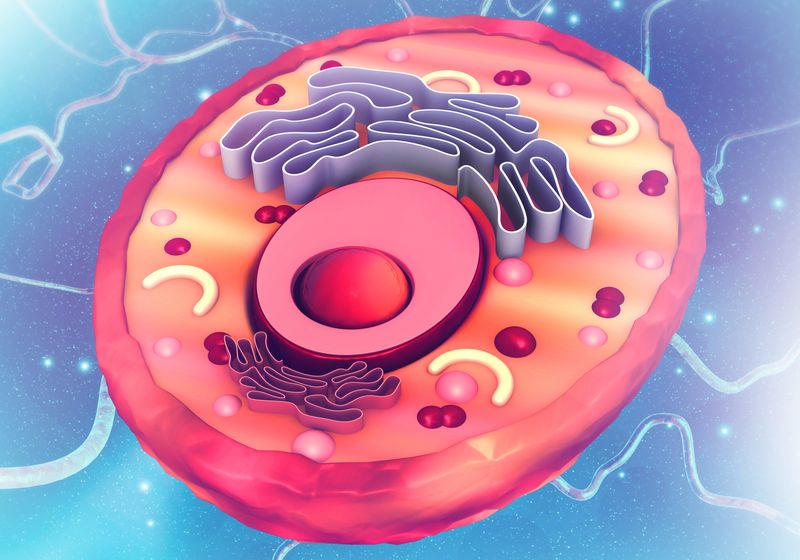

Another question regarding the emergence of complex life revolves around when traits associated with eukaryotes, such as the cytoskeleton, endomembrane system, and nucleus, arose. Using their gene family duplication approach, the researchers mapped when certain traits emerged along the eukaryotic timeline.

They showed that gene families for actin and tubulin from archaea duplicated in early eukaryotes prior to the estimated time of mitochondrial endosymbiosis. Several gene duplications in the endomembrane system not only predated mitochondria but also revealed origins from bacteria distinct from the eventual mitochondria. Duplications in genes related to the spliceosome and RNA polymerase originating from archaea also predated mitochondrial symbiosis.

These findings support the hypothesis that origins for eukaryotes began to take form prior to the introduction of mitochondria.

“What sets this study apart is looking into detail about what these gene families actually do—and which proteins interact with which—all in absolute time. It has required the combination of a number of disciplines to do this: palaeontology to inform the timeline, phylogenetics to create faithful and useful trees, and molecular biology to give these gene families a context. It was a big job,” said Christopher Kay, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bristol and study coauthor, in the same statement.